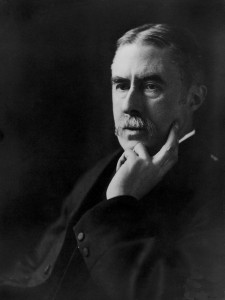

Alfred Edward Housman, born in England on the 26th of March, 1859, was a classical scholar of the highest calibre and a beloved minor poet. His relatively small poetic output focuses on themes of loss, particularly of life and love, and war, which made his works popular during the Second Boer War and World War I, when an entire nation struggled to recover from the callous slaughter of so many of its young boys and men. He was also a homosexual, in a time when to be gay was a criminal offense, and thus his poetry has, I believe quite correctly, been described as among the loneliest in the English language: there is love, but it is unrequited; there is promise, but it goes unfulfilled. Rather than discuss his work in general, I have selected some of his strongest and most exemplary poems – and one atypical one – for discussion.

Alfred Edward Housman, born in England on the 26th of March, 1859, was a classical scholar of the highest calibre and a beloved minor poet. His relatively small poetic output focuses on themes of loss, particularly of life and love, and war, which made his works popular during the Second Boer War and World War I, when an entire nation struggled to recover from the callous slaughter of so many of its young boys and men. He was also a homosexual, in a time when to be gay was a criminal offense, and thus his poetry has, I believe quite correctly, been described as among the loneliest in the English language: there is love, but it is unrequited; there is promise, but it goes unfulfilled. Rather than discuss his work in general, I have selected some of his strongest and most exemplary poems – and one atypical one – for discussion.

The first, from the original volume A Shropshire Lad, has long been one of my favorite poems, and has so penetrated the pop culture ethos as to be referenced in an episode of The Simpsons, where I first encountered it many years ago.

To An Athlete Dying Young

THE time you won your town the race

We chaired you through the market-place;

Man and boy stood cheering by,

And home we brought you shoulder-high.

To-day, the road all runners come,

Shoulder-high we bring you home,

And set you at your threshold down,

Townsman of a stiller town.

Smart lad, to slip betimes away

From fields where glory does not stay

And early though the laurel grows

It withers quicker than the rose.

Eyes the shady night has shut

Cannot see the record cut,

And silence sounds no worse than cheers

After earth has stopped the ears:

Now you will not swell the rout

Of lads that wore their honours out,

Runners whom renown outran

And the name died before the man.

So set, before its echoes fade,

The fleet foot on the sill of shade,

And hold to the low lintel up

The still-defended challenge-cup.

And round that early-laurelled head

Will flock to gaze the strengthless dead,

And find unwithered on its curls

The garland briefer than a girl’s.

The poem is about the death of a young boy and accomplished athlete, and the ephemerality of glory, in athletics as in warfare. Despite his death, the young man is the addressee of the poem, the “you” the narrator constantly refers to. Significantly, the opening two stanzas mirror each other in content: the young boy is being borne aloft, “shoulder-high,” in the first because of his accomplishment in a footrace, in the second, as a corpse being returned home. In the first stanza, he is met with cheers and adulation; in the second, only silence greets him. The third stanza begins by dashing our expectations: “Smart lad”? What is “smart” about getting yourself killed? He is smart for leaving the fields “where glory does not stay,” the field of combat as much as the field of the race. The laurel is a poetic symbol for victory or accomplishment – in ancient Greece and Rome, laurel wreaths were bestowed on victorious athletes or generals – and the rose remains inexorably linked to love and affection.

He will not live to see his records broken, his glories taken from him. He will not join the ranks of the living dead, those whose best days are behind them, who have only mediocrity ahead of them, and who must endure the ignominy of outliving their fame: “Runners whom renown outran, / And the name died before the man.” F. Scott Fitzgerald, in his masterwork The Great Gatsby, echoes this sentiment in a brief description of Tom Buchanan, who is “one of those men who reach such an acute limited excellence at twenty-one that everything afterward savors of anticlimax.” Tom’s “limited excellence” was on the football field, but I’d venture to guess that all of us know people haunted by their past glories and their seeming inability to reproduce them.

After Housman’s death, his brother Laurence gathered together many of his unpublished poems and released them in two volumes: More Poems (1936) and Collected Poems (1939), as well as one of Housman’s personal essays, entitled De Amicitia (About Friendship). In the poems and the essay – which was given to the British Library under the condition that it not be published for 25 years – Housman’s homosexuality is elevated from subtext to subject matter, and much more candidly discussed. The following two poems are from each of these subsequent collections.

XXXI

Because I liked you better

Than suits a man to say

It irked you, and I promised

To throw the thought away.

To put the world between us

We parted, stiff and dry;

Goodbye, said you, forget me.

I will, no fear, said I

The dead man’s knoll, you pass,

And no tall flower to meet you

Starts in the trefoiled grass,

The heart no longer stirred,

And say the lad that loved you

Was one that kept his word.

It is my contention that this poem, despite its obvious homosexual subtext, can be correctly read as a heterosexual love poem as well. Much like Shakespeare’s best love sonnets, which appear in sequences that would suggest he is addressing a man, the poet declines to gender the addressee, intentionally creating an ambiguity that serves equally to mask the homosexual longing of the poet as to open the possibility for a heterosexual reading of the poem. Put more plainly, if the reader did not know that Housman was gay, the only line that hints at that homosexuality – “I liked you better / Than suits a man to say” – could as well be explained by social conventions restricting male emotion. Knowing that Housman is gay, and that homosexuality was criminalized in his day, and that Housman was madly in love with his heterosexual college roommate and lifelong friend Moses Jackson, makes it considerably more likely that the injunction referenced by that line is society’s proscription on homosexuality. To my mind, this is to Housman’s credit: the poem, rather than restricting the possible interpretations, creates an ambiguity that allows for a greater range of interpretation.

The poem itself is emblematic of the aforementioned loneliness and dashed possibility that is latent in much of Housman’s work. He and his beloved part, “stiff and dry,” and the casual construction of their parting serves to underscore this stiffness: “Goodbye, said you, forget me. / I will, no fear, said I.” The narrator’s stubborn adherence to this promise of forgetfulness makes even the flowers surrounding his grave unwilling to rise, offering no consolation to the poet’s beloved, and the poet himself is long dead, with a “heart no longer stirred,” both in the sense that it has ceased to beat and, perhaps, that he has ceased to love.

Oh who is that young sinner with the handcuffs on his wrists?

And what has he been after that they groan and shake their fists?

And wherefore is he wearing such a conscience-stricken air?

Oh they’re taking him to prison for the colour of his hair.

‘Tis a shame to human nature, such a head of hair as his;

In the good old time ’twas hanging for the colour that it is;

Though hanging isn’t bad enough and flaying would be fair

For the nameless and abominable colour of his hair.

Oh a deal of pains he’s taken and a pretty price he’s paid

To hide his poll or dye it of a mentionable shade;

But they’ve pulled the beggar’s hat off for the world to see and stare,

And they’re haling him to justice for the colour of his hair.

Now ’tis oakum for his fingers and the treadmill for his feet

And the quarry-gang on Portland in the cold and in the heat,

And between his spells of labour in the time he has to spare

He can curse the God that made him for the colour of his hair.

The fourteen and fifteen syllable lines, coupled with the simplistic AABB rhyme scheme, lend the poem a kind of energetic focus, with each line reaching a crescendo in its ending, and each stanza peaking in intensity with the inevitable refrain. Indeed, every repetition of “for the colour of his hair” reads like an indictment of the gross injustice of a society that condemns so arbitrarily on the basis of an attribute that Housman is careful to depict as being natural and involuntary. This poem is also an example of dipodic meter, a form of verse consisting of two metrical feet of perceptibly differing stresses, allowing for scansion that deemphasizes words that might otherwise receive emphasis, lending itself to incantatory poetry (Poe’s “The Raven” or Tennyson’s “Locksley Hall,” for example) and giving this poem its sense of unrestrained energy.

Even here, however, when we know the motivation behind the composition of the poem, Housman deals in ambiguities. There is no mention of homosexuality, only coded allusions to the language it was denounced with: “shame to human nature,” “nameless” and “abominable,” for example. The poem could as easily be applied to other heritable or involuntary characteristics that have supplied the grounds for persecution: gender, nationality or ethnicity, to name but a few. In “The Name and Nature of Poetry,” a public lecture he gave in 1933 and the only one on which he draws upon his own experiences as a poet, Housman writes, of a poem by Blake: “That mysterious grandeur would be less grand if it were less mysterious; if the embryo ideas which are all that it contains should endue form and outline, and suggestion condense itself into thought.” We do not normally think of suggestion condensing itself into thought; thought is usually regarded as an expansion of suggestion. In poetry, however, Housman argues that less is more, that the definitive is antithetical to the poetic nature, which longs for possibility. In his most recent work, The Anatomy of Influence, literary critic Harold Bloom writes, in what will surely be the subject of a future blog post of mine: “Thoughts […] are partial recognitions: absolute recognition ends even the most powerful of literary works, since how can fictions continue when truth overwhelms?” Bloom’s point is Housman’s: poetry demands the ironic, the figurative and the ambiguous over the literal, the concrete and the absolute.