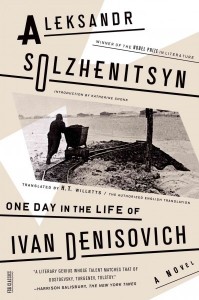

After escaping a German POW camp, Ivan Denisovich Shukhov manages to return to the Red Army with one other escapee, but the mere fact of his survival is enough to cast suspicion on him, and he is sentenced to ten years of hard labor for the crime of being a “political subversive.” The fictional Denisovich provided the West with their first glimpse of the Soviet gulag system, forever shattering the illusion, widely held, that Russia was pioneering a moral, compassionate form of government. Indeed, when One Day In The Life Of Ivan Denisovich first appeared in print in 1962, totalitarianism had become so entrenched in Russia that its mere publication was an event, the first time that the country’s repressive recent past was being openly discussed, acknowledged and criticized. The author, Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, was himself a victim of the gulag system, having endured eight years hard labor for the crime of writing disparaging comments about Stalin in a private letter (see Milan Kundera’s The Joke).

After escaping a German POW camp, Ivan Denisovich Shukhov manages to return to the Red Army with one other escapee, but the mere fact of his survival is enough to cast suspicion on him, and he is sentenced to ten years of hard labor for the crime of being a “political subversive.” The fictional Denisovich provided the West with their first glimpse of the Soviet gulag system, forever shattering the illusion, widely held, that Russia was pioneering a moral, compassionate form of government. Indeed, when One Day In The Life Of Ivan Denisovich first appeared in print in 1962, totalitarianism had become so entrenched in Russia that its mere publication was an event, the first time that the country’s repressive recent past was being openly discussed, acknowledged and criticized. The author, Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, was himself a victim of the gulag system, having endured eight years hard labor for the crime of writing disparaging comments about Stalin in a private letter (see Milan Kundera’s The Joke).

One Day In The Life Of Ivan Denisovich is, superficially, no more than it purports to be, a record of a single day in one man’s life. The author does not indulge in explicit criticism of the gulag system, or the inhumanity of his protagonist’s plight. There are no lengthy philosophical musings and Solzhenitsyn’s prose is intentionally restrained. Instead we are asked, as readers, to contemplate what it would be like to wake up at 5am every morning from a crowded bungalow so poorly insulated that ice forms on the ceiling each night and be marched, at gunpoint, to a work site miles away, where you labor until the late afternoon or early evening in weather so cold that water turns to ice almost as quickly as it can be pumped. “Can a man who’s warm understand a man who’s freezing?” asks our protagonist, and though it’s in reference to one of the guards enjoying an unlimited ration of kindling and the comfort of an insulated guard house, it’s equally applicable to us as readers.

The difficulty of the gulag is not, as we might expect, an existential one. Reading this book, contemplating these men’s fates from a distance, we might well ask ourselves how we would go on, what purpose we might find to sustain us. But the torment of this kind of punishment is just the opposite. When life’s barest necessities cannot be taken for granted, when every morsel of food or the barest reprieve from work can mean the difference between living and dying, the very idea of meaning collapses in on itself.

A convict’s thoughts are no freer than he is: they come back to the same place, worry over the same things continually. Will they poke around in my mattress and find my bread ration? Can I get off work if I report sick tonight? Will the captain be put in the hole, or won’t he?

Each year, Ivan Denisovich Shukhov is entitled to write two letters, but he comes to find even that simple freedom an imposition. “Writing letters now was like throwing stones into a bottomless pool. They sank without trace. No point in telling the family which gang you worked in and what your foreman […] was like.”

In a book dominated by the body and its necessities, it is the absence of the human spirit, its utter silencing, that most frightens.