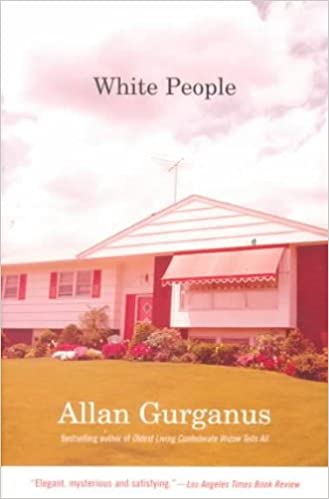

At the close of every year, I survey the neat stacks of books that represent the last twelve months of reading, and take stock of what I’ve read, reminiscing over the writers whose worlds I lived in. One of the great joys of 2020 – one of the few, in fact – was discovering the American writer Allan Gurganus via his fellow novelist and one-time interviewer, William Giraldi. Born in North Carolina in 1947, Gurganus is a Southern writer, but he is not of the South, and that distance – filled with a sense of both affection and alienation – is palpable in his writing, and in the title of his first short story collection, White People (1991). He explores the source of that alienation in some of White People‘s most autobiographical stories, but the totality of the collection escapes easy qualification, for Gurganus is a born storyteller, and all 11 of the tales collected here push against the boundaries of convention, bristle against expectation, delight in their difference.

The collection begins with three quotations designed to hint at the impending theme. One, from a book of etiquette, describes the importance of conversing with your eating partners at a formal dinner (“You MUST, that is all there is about it!”) but goes on to describe how a Mrs. Toplofty once fulfilled this requirement to the absolute minimum: “I shall not talk to you – because I don’t care to. But for the sake of my hostess, I shall say my multiplication tables. Twice one are two, twice two are four –” Another is attributed to the French impressionist painter Edgar Degas: “There is a kind of success that is indistinguishable from panic.” The third comes from the book Life Among the Paiutes, and describes a native American’s first glimpse at the eponymous white people:

They said there were white people at the Humboldt Stink. They were the first ones that my father had seen face to face. He said they were not like ‘humans’. They were more like owls than like anything else. They had hair on their faces, and had white eyes. My father said they looked very beautiful …

Gurganus is preparing us for his authorial stance, which will be closer to that of an outsider than an insider, though one highly attuned to and sympathetic with his subjects. And what does our ethnographer discover, when he trains his sensitivities on “white people”? A success “indistinguishable from panic” – insecurity, frustration, thwarted ambitions, immense and stultifying social pressures. In “Breathing Room,” the narrator – an intellectual destined to disappoint his macho war hero of a father – laments: “Without much accuracy, with strangely little love at all, your family will decide for you exactly who you are, and they’ll keep nudging, coaxing, poking you until you’ve changed into that very simple shape. They’ll choose it lazily. Only when it suits them.” They don’t do so maliciously, however, and it is precisely Gurganus’ sensitivity to that truth, and his ability to convey it to his readers, that makes his stories so compelling and so tragic: it is not just the effete sons one pities, but the bumbling, inept fathers, who cannot relate to them.

Several of the stories deal explicitly with race relations in the American South, and these dramatize a truth once articulated by James Baldwin: “No curtain under heaven is heavier than that curtain of guilt and lies behind which white Americans hide.” One almost envies Gurganus’ black characters, despite their poverty and enforced ignorance and manifold oppressions, for they inhabit a freer, more spontaneous existence than his cramped white characters, whose exploitations weigh heavily on them. This volume’s best story, the 60-page novella “Blessed Assurance,” dramatizes this dynamic with exquisite beauty. Our narrator is a white man, Jerry, reflecting on his youthful employment selling funeral insurance to poor, frequently illiterate black Southerners. This group, his employer explains, is particularly likely to spend extravagantly on their funerals, hoping to achieve in the next life what was denied to them in this one, but their economic insecurity also makes them hugely profitable: no matter how many thousands they invest over years or decades, a single missed payment is enough to nullify their entire insurance plan. Jerry’s boss is emphatic about him killing off his own kindness and not allowing extensions or reprieves: “Once they smell heart on you, kid, you’re lost.” But Jerry, being human, has heart, and when one of his claimants, the 90-year-old Vesta Lottle Battle, begins to miss payments, he cannot bring himself to cancel her insurance, and begins using his own payments to keep her afloat.

The stories of White People are inventive, engrossing, and often wickedly funny. Gurganus is also an excellent stylist, deftly reproducing the uptight tone of white Southern aristocrats and the jocular ribbing of the black rural underclass, in a language that is every bit as dynamic and sonorous as the American South. The result is one of the finest American short story collections I’ve ever read.