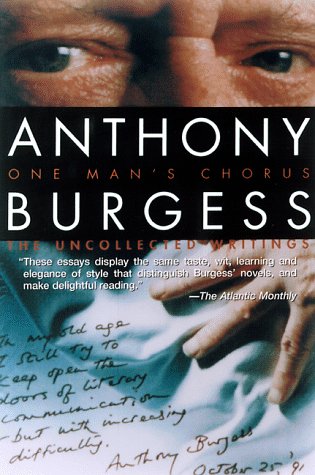

I recently came across Milton’s famous lines, from “Areopagitica,” about a good book being “the precious lifeblood of a master spirit, embalmed and treasured up on purpose to a life beyond life.” Neither time nor overly enthusiastic quotation of those lines can dull their force, and the truth of them seems to me reinforced every time I read a good book. I will never meet Anthony Burgess, author of dozens of novels and composer of hundreds of musical works, but his essays are indeed the work of a master spirit, and I am glad to have encountered them. One Man’s Chorus appeared only after his death, collecting his “uncollected” writings on subjects as various as travel, politics, art, music and literature, and the general rule, with such posthumous projects, is that they are to be avoided: they typically represent a publisher’s last-ditch effort to capitalize on an author’s fame by scraping together writing they did for a paycheque between larger, more meaningful projects. This particular selection, however, was put together with loving care by his friend and admirer Ben Forkner, and whether it was his concerted efforts or simply Burgess’ unfailing genius, the pieces are excellent from top to bottom.

Writers are not prophets, and yet all great writing is somehow prophetic, perhaps because the truths the writers uncover or embody are eternal, and therefore bound to recur or reemerge. The majority of these essays were composed in the 1980s, and yet they appear to me, in 2019, to be remarkably prescient. Burgess was perhaps better able to be objective about European and British politics because of his permanent outsider status: he left England in 1954, to join the British Colonial Service, and again in the early 1960s, this time to escape the exorbitant 90% income tax of the post-war ’50s and ’60s. Sensibly enough, for a man with money on his mind, he left England for Monaco, and thus the first essay of the collection, “The Ball is Free to Roll,” describes the founding of Monaco’s first casino – and the city-state that grew up in its wake. “Something About Malaysia” gives us our first introduction to Burgess the polyglot – he spoke French, Russian, Spanish, Italian, Welsh and Malay, with smatterings of Chinese, Japanese, and Persian, on top of the requisite Latin literacy, for good measure – as he describes his five-year stay in that country, together with a brief introduction to its history and its racial divisions (“Pygmies with blowpipes are at one end of the social scale, while at the other are the Chinese millionaires”). It is here that we get a representative sample of his particular humour, straddling the line between sly and sincere:

I am strongly drawn to the life of the kampong, and there was a time – in 1957, independence year – when I resisted repatriation and wanted to be accepted as a genuine Malayan. I proposed entering Islam, which would have entitled me to four wives but barred me from eating ham for breakfast. My name was chosen for me – Yahya bin Abdullah – and I started to study the Koran. It was an agreeable prospect. The weather is nearly always fine, like an English May, and the sweat flows delightfully. For some reason the tropics bestow on white men a great appetite for sensuality – food, drink, and sex – whereas white women dwindle and die. I would marry four Malay wives and beget a host of particoloured children who would respect me and call me bapa. I would make the pilgrimage to Mecca and come back wearing a turban with the title Haji. Haji Yahya bin Abdullah. I would be a known and beloved figure at the mosque meetings on Friday, and I would die, full of years, under that benign sun, among those green leaves.

Four wives but no ham. We can almost see him winking at us between the words. Sly ambivalence, in fact, characterizes much of his writing on travel and politics, perhaps because, as Forkner suggests in his introduction, “He was a novelist, not a spokesman, and he shunned the robe of the pontiff like a poisoned shirt.” That doesn’t preclude him from offering opinions, of course. In “Thoughts on the Thatcher Decade,” we are told that “There is little evidence in contemporary British life that it is considered better to help the sick and suffering than to kick them in the face,” and in “England in Europe” (of dire relevance in the post-Brexit era) we get these gems: “A question that must be asked is: how European is England? I, as an Englishman, would reply: Hardly at all” and “Europe is not a unity: it is half Catholic and half communist. England likes neither faith.”

Fittingly, the best essays deal with literature and music – two Burgess specialties, if a man of so many talents can be said to have specialties. Joyce, Milton and Shakespeare – all of whom get essays unto themselves – seem particularly important to Burgess, though his critical eye extends to Graham Greene, Virginia Woolf, Gerard Manley Hopkins, Tolkien, Yeats and Waugh as well. His essay on the practice of writing – “Craft and Crucifixion,” of course – testifies to a lifetime of prodigious effort (1,000 words a day, every day, for decades) and middling reward (“The novelist is on his own, and, even when he gets to heaven he will probably be coldshouldered by Flaubert and Proust. But God, who is the supreme novelist, may love him. After all, he has permitted his crucifixion”). James Joyce is spoken of with a reverence and depth of knowledge equalled only by his famous biographer, Richard Ellmann, and the trilogy of essays on T.S. Elliot taught me more about the 20th century’s most influential poet than semester-length university courses. Indeed, to read The Waste Land through Burgess’ eyes is a privilege that more than repays the cost of this book.

I have yet to encounter Burgess the novelist, but in a single work he has distinguished himself, in my eyes, as a singularly gifted literary critic and essayist. The novels will follow shortly.