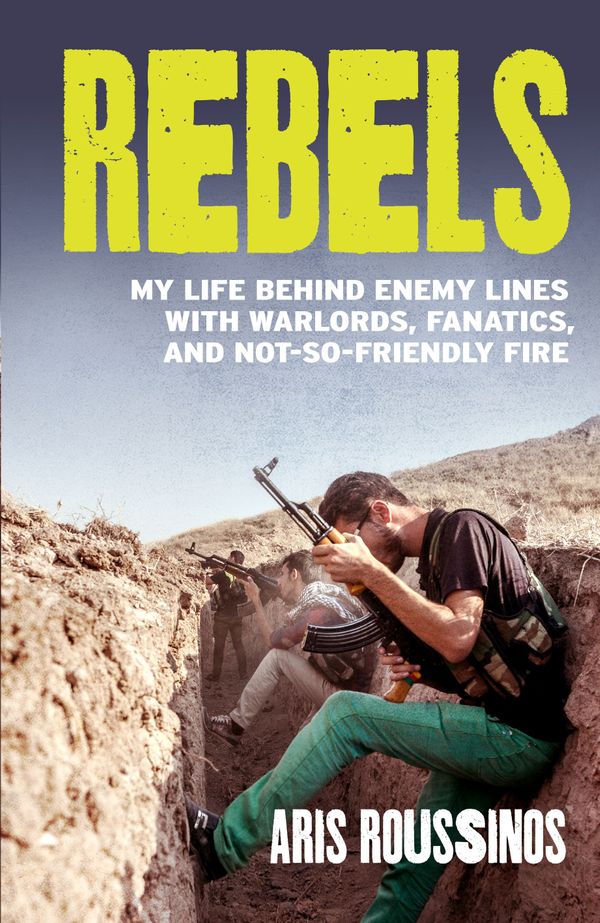

For some years now, I have enjoyed the writings of Aris Roussinos, a former war reporter turned opinion writer with a particular interest in the lifecycles of civilizations, the blindspots of modern liberalism, and the barriers and pathways to cultural commingling. In Rebels, thus far his only published work, he describes his childhood ambition to join the British military and the subsequent injury that dashed his hopes of war glory. In 2011, at the outbreak of the Arab Spring and while still in his twenties, he saw a second opportunity for danger, and quickly sought a press pass at a news agency that covered the Middle East. “From Sudan to Syria, Libya to Mali, I’ve hung out with the men who took up arms against their governments, and with the government forces trying to hunt them down and kill them. As a freelancer, I followed the wars that would sell and tried to sell the wars the world doesn’t care about.” Roussinos doesn’t promise us grand narratives or wisened political analysis. He’s offering a boots-on-the-ground look at combat. “This is what the world looks like to me,” he tells us, before launching into his story.

His earliest reporting is on the Libyan Civil War, and he begins this not by offering us the usual bromides about war’s evil, but by launching immediately into the source of war’s unique allure: “The hidden awful truth about war is how much fun it is. Everything else becomes an afterthought, dragged into the slipstream of its exhilarating violence. […] Young men do this, and they enjoy it.” Death is all around him, of course: there are bodies being picked apart by carrion, snipers loyal to Gaddafi embedded in downtown high-rises, even the odd journalist unlucky enough to get too close to the action, but these too are “dragged into the slipstream,” subordinated to the larger goal of the rebels to reclaim their country. For most of his travels, Aris is operating as a freelance journalist, which shapes his travels in two important ways: he does not have the large budget or support network of his peers at mainstream news agencies, and his take-home pay is largely a function of the footage he can sell: action-intensive without being gory, or grotesque, or depressing, as these would disqualify it from international broadcasting. Luckily for him, most of the fighters he encounters are eager to be interviewed, desperate to feel that their struggle might receive an audience. More than a few of them even request a copy of the footage, for sharing on their private Facebook pages.

Rebels offers little in the way of wide-angled political analysis, and only a cursory outline of the origins of each conflict reported on. It doesn’t purport to be more than on-the-ground reporting, as witnessed by a brave, honest and somewhat foolish British man, who rapidly becomes intoxicated in the life-and-death drama he’s tasked with reporting on. It is, however, a gripping read, and a window into these conflicts rarely opened to Western readers.