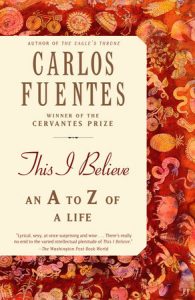

There is an entire sub-species of autobiography, generally written in the twilight of a man’s life, when he knows that the best is behind him and all that remains is the terrifying silence of death. Nothing focuses the mind quite like the prospect of its own demise, so, paradoxically, much of the writing in this genre possesses rare vitality, expressed with the urgency of the nearly departed. On the other hand, nothing undoes a man faster than the prospect of his own demise, and no doubt, for most people, death functions better as a theoretical deadline than a concrete one. This, unfortunately, is the case for This I Believe, the last nonfiction work by Mexican writer Carlos Fuentes to appear in translation before his death in 2012.

There is an entire sub-species of autobiography, generally written in the twilight of a man’s life, when he knows that the best is behind him and all that remains is the terrifying silence of death. Nothing focuses the mind quite like the prospect of its own demise, so, paradoxically, much of the writing in this genre possesses rare vitality, expressed with the urgency of the nearly departed. On the other hand, nothing undoes a man faster than the prospect of his own demise, and no doubt, for most people, death functions better as a theoretical deadline than a concrete one. This, unfortunately, is the case for This I Believe, the last nonfiction work by Mexican writer Carlos Fuentes to appear in translation before his death in 2012.

The problems begin with the book’s structure. It’s billed as “An A to Z of a Life,” but in practice life has far more A’s, R’s and T’s than X’s, Y’s and Z’s, and the essays on “Xenophobia,” “You and I” and “Zebra” read like concessions to this fact. So, too, does his decision to overload some words, giving us, for example, three essays inspired by the letter B, and four by the letters C and F. All of this might be forgivable if the essays themselves were of the highest quality, but neither the writing nor the insights conveyed maintain their consistency. Part of this, no doubt, can be blamed upon their brevity: a handful of pages are not enough to convey a great deal of information on Death, Globalization or Freedom without descending into platitudes. Take this sentence, for example, in his essay on Education: “The university is a stage – no doubt the most important one – in an educational process that begins in primary school and continues on in the perpetual school we all attend: that is, the education of life.” To casually invoke a stale cliché (the “school of life”) is a low-level offence, but a writer that elevates that same cliché to the culminating point of a sentence betrays not only sloppy craftsmanship but sloppy thinking as well. Consider his essay on Globalization – as timely a topic as we could ask for, as we live through a period of nationalist resurgence. Fuentes correctly describes globalization as “a power system” with two aspects, one beneficial and one harmful, but then goes on to dismiss international terrorism – as powerful an embodiment of harmful globalism as presently exists – with empty platitudes:

The tragedy of September 11, 2001, horrified everyone and confirmed for all of us that terrorism is a universal fact. It must be fought with tenacity wherever it manifests itself, but without demonizing entire nations or cultures. We cannot fall into the preposterous trap of attributing terrorism to a historical hatred of the United States, to the corruption or inefficiency of certain Islamic governments, and much less to the clash of cultures. No: we most certainly should agree that the deepest sources of conflict in our world are instability, illegality, poverty, exclusion, and, in general terms, the absence of a new legality for a new reality.

This is a remarkable excerpt, for it dismisses the stereotypical explanations of both right and left – “historical hatred of the United States,” rooted in colonialism or military interventions, and the “clash of cultures” hypothesis – in favor of blaming poverty, exclusion, instability and “illegality,” or the “absence of a new legality.” Do Pakistan and Somalia bear no responsibility for harbouring terrorists? Do Iran and Saudi Arabia bear no responsibility for financing terrorist plots? What “illegality” causes terrorism, and what new “legality” would put a stop to it? Fuentes goes on to offer a solution I find astonishingly naive: “[…] it is important to begin building, step by step, the foundations of an international legal body for the global age.” What kind of legal entity would the countries of the Western world and the countries of the Middle East consent to join, given their chasmic disagreements on fundamental questions of politics, law and the place of religion in public life? Fuentes does not even attempt to provide an answer.

There are, of course, redeeming aspects to this book. Fuentes writes much more thoughtfully about literature than about politics, and he has travelled widely enough, lived well enough and long enough, that his anecdotes about people and places compel our attention. These, unfortunately, do not suffice to justify This I Believe, or excuse its glaring shortcomings.