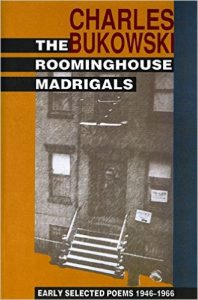

There is a popular image of the poet as tortured soul, constitutionally at odds with existence itself, self-medicating with drugs or alcohol and tapping out poetry on a typewriter between hangovers. The poets themselves are often at least partially to blame for misleading the public – who honestly believes Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s claim to have conceived of “Kubla Khan,” in toto, during an opium dream? – but few poets so consistently cultivated this image as Charles Bukowski, irascible drunk and professional bohemian. With Bukowski, as with the Beat poets, I am never certain if the allure lies in the poetry or the poet, with the verses or the vie bohème, and I undertook this reading with that question in mind.

There is a popular image of the poet as tortured soul, constitutionally at odds with existence itself, self-medicating with drugs or alcohol and tapping out poetry on a typewriter between hangovers. The poets themselves are often at least partially to blame for misleading the public – who honestly believes Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s claim to have conceived of “Kubla Khan,” in toto, during an opium dream? – but few poets so consistently cultivated this image as Charles Bukowski, irascible drunk and professional bohemian. With Bukowski, as with the Beat poets, I am never certain if the allure lies in the poetry or the poet, with the verses or the vie bohème, and I undertook this reading with that question in mind.

Bukowski’s poetry stands out for his poetic voice, prevalent in almost every poem: the hard I of someone who works with his hands, who drinks through the night, who sleeps around, whose life’s direction has been orthogonal to convention and expectation almost from birth. His poems are angry, desperate, or resigned, never whimsical, happy or optimistic; they are full of disdain for the world and its hypocrisies, and the challenges of living among fools or making art. Here is “The Genius of the Crowd,” one of his most anthologized poems, made famous by social media:

there is enough treachery, hatred violence absurdity in the average

human being to supply any given army on any given dayand the best at murder are those who preach against it

and the best at hate are those who preach love

and the best at war finally are those who preach peacethose who preach god, need god

those who preach peace do not have peace

those who preach peace do not have lovebeware the preachers

beware the knowers

beware those who are always reading books

beware those who either detest poverty

or are proud of it

beware those quick to praise

for they need praise in return

beware those who are quick to censor

they are afraid of what they do not know

beware those who seek constant crowds for

they are nothing alone

beware the average man the average woman

beware their love, their love is average

seeks averagebut there is genius in their hatred

there is enough genius in their hatred to kill you

to kill anybody

not wanting solitude

not understanding solitude

they will attempt to destroy anything

that differs from their own

not being able to create art

they will not understand art

they will consider their failure as creators

only as a failure of the world

not being able to love fully

they will believe your love incomplete

and then they will hate you

and their hatred will be perfectlike a shining diamond

like a knife

like a mountain

like a tiger

like hemlocktheir finest art

I have seen this poem shared over images, transcribed in paragraph form, and I find that somehow apt, for its form aside, it reads like prose, approaching the kind written by shallow self-help gurus. And conceding that I find it to contain some important truths, that it has an inspirational quality to it, does nothing to improve its poetic qualities, which rest on a few short images and the repetition of choice words. Samuel Johnson famously chided the poets of his day for believing that “not to write prose is certainly to write poetry,” and Bukowski, at his worst, runs afoul of this dictum. Here, for example, are the opening lines to “Mother and Son”:

a lady in pink sits on her porch

in tight capris

and her ass is a marvelous thing

pink and crouched in the sun

her ass is a marvelous thing,

and now she rises and claps her hands

toward the sea

Bukowski is attempting to capture something ugly in this poem, a mother he has slept with and the future he imagines for her son (“he might put on a necktie / choke out the mind / and become like the rest”), but an ugly subject matter cannot excuse these weak lines. In “With Vengeance Like a Tiger Crawls,” he offers a kind of justification for his anti-poetry, his eschewal of meter and rhyme and even rhythm:

to hell with metric – I have read the lore of the ages

and placed them back on their lifeless shelves:

we have written ourselves insensible

while outside…

One thinks of Theodore Adorno’s famous remark, that to write poetry after the Holocaust was barbaric – to hell with it! Bukowski seems to believe that poets have become disconnected from reality, insensitive to the cold realities of the life he has seen first-hand, though if he was sincere in this conviction, we’re entitled to wonder why meter should be discarded and not poetry in its entirety.

He is at his best when he can find some harmony between his musings and his arresting imagery, when he can vivify the ugliness he sees with an image that doesn’t itself partake of that ugliness but somehow uplifts or venerates it – when he likens our ability to luxuriate in agony to “an old lady putting on a red hat,” for example. “I am a beggar,” he declares in one poem, “hoisting lulled / sacked thoughts, / knowing I have the bolt to throw / but the catcher’s out of sight.” This, very likely, was composed before he found his audience, his catcher, but it remains a pity to me – and a judgment against Bukowski – that “lulled sacked thoughts” is such an apt description of so many of these poems.