Charles Murray is a political scientist best known for his Losing Ground: American Social Policy, 1950-1980 (1984) and the book on intelligence that he co-authored with the late Richard Hernstein, The Bell Curve: Intelligence and Class Structure in American Life. The former argued that certain welfare reforms were harming those they were designed to help, and quickly became one of the most influential books on American policy in the 20th century; it has been credited with catalyzing welfare reforms. The latter has been mired in controversy since its publication, largely thanks to its contention that IQ differences are observable across ethnic and racial groups and between men and women, and has made Murray the target of a great deal of public scorn. He has been called, variously, a “white nationalist” and a “racist pseudoscientist” as well as – perhaps the only flattering epithet – “the most dangerous man in America.” I had heard of The Bell Curve but wouldn’t have known Murray to be the author until I came across an open letter he wrote to the students of Azusa Pacific University in response to his speaking offer being retracted, ostensibly to protect student well-being. In the letter, Murray challenges the students to hear him speak on YouTube or read his works for themselves rather than accept a second-hand opinion, and I promptly answered that challenge. I am extremely glad I did.

Charles Murray is a political scientist best known for his Losing Ground: American Social Policy, 1950-1980 (1984) and the book on intelligence that he co-authored with the late Richard Hernstein, The Bell Curve: Intelligence and Class Structure in American Life. The former argued that certain welfare reforms were harming those they were designed to help, and quickly became one of the most influential books on American policy in the 20th century; it has been credited with catalyzing welfare reforms. The latter has been mired in controversy since its publication, largely thanks to its contention that IQ differences are observable across ethnic and racial groups and between men and women, and has made Murray the target of a great deal of public scorn. He has been called, variously, a “white nationalist” and a “racist pseudoscientist” as well as – perhaps the only flattering epithet – “the most dangerous man in America.” I had heard of The Bell Curve but wouldn’t have known Murray to be the author until I came across an open letter he wrote to the students of Azusa Pacific University in response to his speaking offer being retracted, ostensibly to protect student well-being. In the letter, Murray challenges the students to hear him speak on YouTube or read his works for themselves rather than accept a second-hand opinion, and I promptly answered that challenge. I am extremely glad I did.

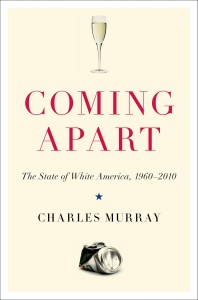

Coming Apart: The State of White America, 1960-2010 has a basic thesis, one that speaks to so much of what I have been reading and studying: America is indeed coming apart along class lines, the result of an ever-growing rift between rich and poor, but the cause may very well be more complex than the disappearance of the manufacturing industry, the repealing of Glass-Steagall or low tax rates on the highest income earners. Worse still, the wealthy and highly educated are increasingly segregating themselves, both in body and spirit, from the mainstream of America, creating a ruling class that is effectively oblivious of those they rule over. The intelligent and well-to-do attend prestigious colleges, move into one of only a small handful of major cities (and are even more selective when it comes to which neighborhood), take on lucrative and rewarding careers and then marry a spouse of similar levels of education and achievement. This power couple’s child receives not only all of the financial benefits that accrue from having two high-earning parents (tutors, extracurricular activities, private schools) but may in fact get a cognitive benefit as well, thanks to the heritability of intelligence.

But, according to Murray, the increasing segregation between rich and poor is equally attributable to the missteps of the poor – an accusation sure to offend. For the sake of brevity, I will confine myself to discussing marriage. There is an unfortunate hierarchy that exists when it comes to child well-being: children of stable families do remarkably better than children of broken homes, and both groups trounce children of “never-married mothers.” What do I mean by “do better”? You can take your pick. By nearly every metric we have (grades, high school graduation, rates of learning disorders, criminality or emotional disturbance, future income, civic participation), two parents overwhelmingly outperform one. And yet to say so is a cultural taboo. As Murray puts it, “I know of no other set of important findings that are as broadly accepted by social scientists who follow the technical literature, liberal as well as conservative, and yet are so resolutely ignored by network news programs, editorial writers for the major newspapers, and politicians of both major political parties.” The importance of a stable marriage to child welfare is at least superficially understood by the wealthy and well-educated; they put off marriage longer, marry at a higher rate and are less likely to divorce.

The aforementioned segregation of the wealthy and well-educated results in upper class marriages of unprecedented wealth, exacerbated by what Murray calls “homogeneity,” the tendency for likes to attract. Gone are the days when a doctor would marry the girl next door, or when a lawyer might marry his secretary. The entrance of women into the workforce coupled with the vast improvements college admissions offices have made in seeking out America’s “best and brightest” have created a dating pool separate from the rest of the country. New York Times columnist Ross Douthat has written an excellent column on this exact subject, provokatively entitled “Social Liberalism As Class Warfare,” that ends with this harrowing sentence:

It is still a reality of contemporary life that when anyone can get a divorce for any reason, the lower classes seem to get far more of the divorces, and that when anyone can get an abortion for any reason, the poor end up having more abortions and more children out of wedlock both.

If Murray and Douthat are right, if the growing rift between upper and lower classes has as much or more to do with social changes than it does with government policy, the solution won’t be legislative, a different tax code or extra incentives propping up marriage. It will require a corresponding social change.