In yet another sad commentary on the state of intellectual debate in higher education, Christina Hoff Sommers required a police escort to deliver her talk “What’s Right (And Badly Wrong) With Feminism” at Oberlin University (note, the link is from the same speech given at Georgetown, where the audience at least remained civil). Posters outside the event denounced her as a “supporter of rapists” and chided her for her “internalized misogyny,” while a group of brave students stood in the back of the room, red tape over their mouths, in apparent protest of the “silencing” effect her mere presence would have on the campus. Then, before she could speak, two students rose to the front to offer what has become de rigueur anytime coddled undergraduates feel threatened by ideas: an alternate venue designated as a “safe space.” What we are witnessing is not the defense of an idea but the guarding of an orthodoxy, and if today’s inquisitors have traded in smocks and habits for nose rings and dyed hair, they’re scarcely less effective at silencing debate or punishing heretics. Christina Hoff Sommers was excommunicated in 1994, upon the release of Who Stole Feminism?, but she has continued – to borrow a popular phrase – speaking truth to power via her Factual Feminist Youtube channel.

In yet another sad commentary on the state of intellectual debate in higher education, Christina Hoff Sommers required a police escort to deliver her talk “What’s Right (And Badly Wrong) With Feminism” at Oberlin University (note, the link is from the same speech given at Georgetown, where the audience at least remained civil). Posters outside the event denounced her as a “supporter of rapists” and chided her for her “internalized misogyny,” while a group of brave students stood in the back of the room, red tape over their mouths, in apparent protest of the “silencing” effect her mere presence would have on the campus. Then, before she could speak, two students rose to the front to offer what has become de rigueur anytime coddled undergraduates feel threatened by ideas: an alternate venue designated as a “safe space.” What we are witnessing is not the defense of an idea but the guarding of an orthodoxy, and if today’s inquisitors have traded in smocks and habits for nose rings and dyed hair, they’re scarcely less effective at silencing debate or punishing heretics. Christina Hoff Sommers was excommunicated in 1994, upon the release of Who Stole Feminism?, but she has continued – to borrow a popular phrase – speaking truth to power via her Factual Feminist Youtube channel.

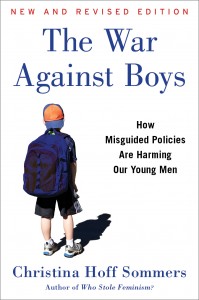

The War Against Boys was published in 2000, when trends in education – at all levels, and in all subject matters – pointed to the emergence of a dismaying “gender gap.” Boys, it seemed, were falling behind girls by almost every quantifiable metric, reflected most clearly in college attendance, where women now make up nearly 60% of all undergraduates. Sommers notes that the gap is largest in reading and writing skills, where the average male high school graduate is often two and three years, respectively, behind his female peers. The War Against Boys was among the first books to address the educational woes of young boys, but the wider public has begun to take notice. We are now inundated with books proclaiming The End Of Men (Hanna Rosin) or The Demise Of Guys (Philip Zimbardo) – such compassion!

Sommers’ work is different. Consider, once more, the title, with its implication of malicious intent. This is not, Sommers contends, some regrettable accident, a problem that only needs to be named before it can be addressed. On the contrary, it is the predictable result of particular policies, implemented on the basis of a particular ideology. Whence comes this failure to educate young boys, so utterly without precedent in over two thousand years of Western history? From our very inability to recognize that they are boys, that boyhood presents particular challenges and necessitates a particular approach to education. For the better part of half a century, our universities have been saturated with post-modernist theories that have proclaimed, among other inanities, that gender is a social construct. In practice, this has meant decades of public policy and teacher training built on what, to a biologist, is an egregious falsehood.

Do boys and girls learn differently? Does educating boys present different challenges than educating girls? Yes on both counts, Sommers contends. Boys are more rambunctious, more competitive, less able to sit still for hours on end and unlikely to enjoy cooperative assignments. They need regular physical activity, just as young girls do, but boys are more likely to engage in what Sommers calls “rough-and-tumble play” – though I confess, looking back on my boyhood, it seemed more akin to mock warfare. Most of these prescriptions will no doubt strike the average reader as being, well, obvious, commonsensical. But whole curriculums and disciplinary codes have been written that give credence to that oft-repeated aphorism, Common sense is not so common.

Tug of war has become “tug of peace.” Gold stars and trophies are awarded for participation and score-keeping is considered damaging to the delicate self-esteems of developing children. And then there are the disciplinary codes, which have increased in severity in the wake of Columbine. Sommers cites the work of Carol Gilligan, who claimed to have discovered the provenance of male sociopaths and school shooters. They are not, Gilligan contends, exceptions or aberrations, some horrifying confusion of mental illness, anger and neglect; no, they are the embodiment of a hyper-masculine culture, one that raises young boys to glorify violence and competition at the expense of compassion and empathy. Masking contempt for men with compassion for boys, Gilligan inaugurated an hysteria that continues to this day, one that sees in every young boy playing cops-and-robbers the makings of a future delinquent or mass murderer. Sommers reports on cases of young boys, some barely ten years old, being disciplined for playing with G.I. Joe’s or chewing a slice of pizza into the the shape of a gun.

For having the audacity to challenge the social constructionist dogma, for pointing out the machinations of powerful lobbying groups like the National Organization for Women (NOW) and the American Association of University Women (AAUW) in their attempts to downplay or even deny the struggles of young boys in our education system and actively oppose measures that have proven to help (single-sex education is “gender segregation,” according to these groups), Sommers has been labeled a heretic. To chart her career’s progression, to read what she has to say and contrast it with how she is treated in the popular media or in academic circles, is to lose all faith in our so-called intelligentsia. Then again, watching her popularity grow on the Internet and social media almost gives me hope.