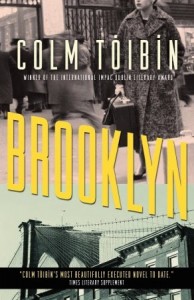

For a tiny island nation with a population under seven million, Ireland boasts more than its share of brilliant writers, from Swift down to Yeats, Shaw, Joyce, Beckett and the late Seamus Heaney. Is it inspirational scenery? or perhaps the dialect? maybe the British are to blame (thank?), for enforcing a kind of negative identity on Ireland and its people? Questions of identity, of what it means to be Irish, are at the center of Colm Tóibín’s Brooklyn, a novel whose young protagonist Eilis Lacey (re: the pronunciation, your guess is as good as mine) leaves her quiet Irish life in search of employment and opportunity in 1950s Brooklyn.

For a tiny island nation with a population under seven million, Ireland boasts more than its share of brilliant writers, from Swift down to Yeats, Shaw, Joyce, Beckett and the late Seamus Heaney. Is it inspirational scenery? or perhaps the dialect? maybe the British are to blame (thank?), for enforcing a kind of negative identity on Ireland and its people? Questions of identity, of what it means to be Irish, are at the center of Colm Tóibín’s Brooklyn, a novel whose young protagonist Eilis Lacey (re: the pronunciation, your guess is as good as mine) leaves her quiet Irish life in search of employment and opportunity in 1950s Brooklyn.

Eilis is young, naive and weak-willed. Her father died when she was younger, forcing her brothers to go to England in search of employment. She lives with her mother and her older sister, Rose, who works full time at a golf club to supplement their mother’s meager pension. Tóibín has a psychological acuity that invests these domestic relationships with the highest importance. The mother, widowed, lonely and with poor financial prospects, shifts her emotional burdens onto her daughters. Rose, the elder sibling, takes on a greater share of this burden in the hope of shielding Eilis. But when a priest from Brooklyn arrives with a job offer, both Rose and her mother conspire to send Eilis to America.

Tóibín traces Eilis’ maturation from youthful innocence into something like maturity with deftness. The first step on this journey comes when she must face her utter solitude, confront full on the fact that she is without friend or family in a foreign world. This also marks the first time that she can see her family with something approaching objectivity, for it is they who were responsible for sending her away.

None of them could help her. She had lost all of them. They would not find out about this; she would not put it into a letter. And because of this she understood that they would never know her now. Maybe, she thought, they had never known her, any of them, because if they had, then they would have had to realize what this would be like for her.

Away from her family, Eilis builds an identity for herself separate from her role as sister and daughter, and it is a great pleasure to watch her rise from her childlike innocence and ineptitude into self-confidence, but there is, Tóibín seems to suggest, a price to be paid for this maturity. The loss of innocence spawns a second consciousness, an ability to see more clearly the motives and intentions of others, and inevitably following this, the temptation to lie and deceive.

One of the great pleasures of Brooklyn is in experiencing America through the eyes of an immigrant, of being made to feel the strangeness of its culture and customs as only a displaced person can. In Ireland, Eilis worked in a general store for a lady who had no patience for outsiders and conferred blatant favoritism on the well-to-do. When Eilis arrives in Brooklyn, she begins another retail job, but under a very different philosophy, one shaped by capitalism and the profit necessity. Thus her new boss informs the store’s employees:

New people arrive and they could be Jewish or Irish or Polish or even coloured. Our old customers are moving out to Long Island and we can’t follow them, so we need new customers every week. We treat everyone the same. We welcome every single person who comes into this store. They all have money to spend. We keep our prices low and our manners high. If people like it here, they’ll come back. You treat the customer like a friend.

What is prejudice compared to the need to make a buck?

Tóibín is a consummate storyteller, weaving into the narrative what social commentary or philosophical insight he pleases without distracting from his story or risking his reader’s attentions, and Brooklyn is a powerful testament to the transportive powers of fiction.