In 1845, two ships, the HMS Erebus and HMS Terror, set out from Britain as part of a naval expedition to discover and chart the Northwest Passage, a sea route connecting the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans via the Arctic Ocean. The expedition was led by Sir John Franklin, a veteran of the Arctic, and comprised 129 men provisioned for up to five years. They were never heard from again. Subsequent rescue expeditions turned up neither the ships nor surviving crew, but evidence of a frightening fate: corpses ravaged by scurvy, frostbite and starvation, as well as deep cutting marks on the bones suggestive of cannibalism. Not until the last five years have Arctic researchers, equipped with sophisticated sonar and diving gear, managed to locate the final resting place of both ships, but their discovery has done little to dispel the mystery surrounding the expedition or the fate of its crew. No doubt that sense of mystery was what first attracted American author Dan Simmons to the story, when he happened across it in a footnote and decided to concoct his own nightmarish fate for Franklin’s men. The resulting book, The Terror, melds historical reality with Inuit myth, producing not only a harrowing thriller but a frightening look at human behaviour when food is scarce and death is near.

In 1845, two ships, the HMS Erebus and HMS Terror, set out from Britain as part of a naval expedition to discover and chart the Northwest Passage, a sea route connecting the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans via the Arctic Ocean. The expedition was led by Sir John Franklin, a veteran of the Arctic, and comprised 129 men provisioned for up to five years. They were never heard from again. Subsequent rescue expeditions turned up neither the ships nor surviving crew, but evidence of a frightening fate: corpses ravaged by scurvy, frostbite and starvation, as well as deep cutting marks on the bones suggestive of cannibalism. Not until the last five years have Arctic researchers, equipped with sophisticated sonar and diving gear, managed to locate the final resting place of both ships, but their discovery has done little to dispel the mystery surrounding the expedition or the fate of its crew. No doubt that sense of mystery was what first attracted American author Dan Simmons to the story, when he happened across it in a footnote and decided to concoct his own nightmarish fate for Franklin’s men. The resulting book, The Terror, melds historical reality with Inuit myth, producing not only a harrowing thriller but a frightening look at human behaviour when food is scarce and death is near.

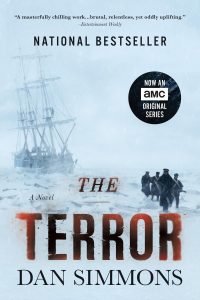

A confession, before I begin: I had never heard of Dan Simmons, or his novels, prior to watching the first episode of AMC’s adaptation of The Terror, and it was on the strength of that pilot episode – and my determination not to ruin the novel by finishing the television series first – that I raced to my local bookstore. The novel begins two years into the expedition, when both Terror and Erebus have been trapped in unrelenting pack ice for nearly two years. Simmons does a masterful job evoking this extreme setting: the bone-chilling cold, the oppressive whiteness of the landscape, and the constant background noise of the pack ice pushing against the exterior of the ships, stressing the thick oak planks and metal bands that are all that separate the crew of the two ships from crushing doom. “In this cold,” Simmons tells us, “teeth can shatter after two or three hours – actually explode – sending shrapnel of bone and enamel flying inside the cavern of one’s clenched jaw.” Deadlier even than the elements, however, is a monster that stalks the men night and day, picking them off one at a time; larger and faster and more cunning than any predator they have ever encountered, it seems impervious to bullets and shotgun pellets, and fixated not only on killing the crew but on tormenting them as well: at various points, it leaves the dismembered bodies of its victims in plain sight, or mixes one man’s lower body with another’s torso.

Simmons tells his story from multiple perspectives, with each character based on a living counterpart from the actual voyage. There are the captains, James Franklin – an arrogant teetotaler, less popular with the men than he images – and Francis Crozier, an alcoholic Irishman whose nationality has stymied his progress up the ranks of the Royal Navy, as well as a doctor, Harry Goodsir, and a handful of crewmen of varying ranks. Our sympathies, as readers, are plainly meant to lie with Francis Crozier, the man responsible for keeping his crew alive in the face of pitiable odds, and by giving us multiple perspectives, as well as retrospective episodes that shed light on the characters’ fates, we glimpse an impending mutiny long before the officers do. This structure, involving multiple narrative perspectives across varying timelines, gives Simmons total control over his plot, and like a master storyteller he exploits every angle to create the maximum of suspense and tension.

Simmons is unabashedly a genre writer, having written some 30 books spanning science fiction, horror, biography, fantasy and history, but unlike so many genre writers, who rely on plot to interest the reader and distract from a dull prose style, he writes with genuine attention to rhythm and a metaphorical inventiveness rivalling any of his contemporaries. In researching him, I stumbled across his blog, where I learned that, aside from being an accomplished writer, he has decades of experience teaching the craft – something very evident in his “Writing Well” section, where he supplies insights culled from a lifetime of not only writing but reading, and reading at a very high level: Hemingway, Proust, Henry James, and my hero, William H. Gass. In other words, I am deeply, deeply impressed by Dan Simmons, and hopeful that his newfound television presence will lead others to discover his writing.