Crime and detective fiction have never been of particular interest to me, but the late British writer Derek Raymond – real name Robert William Arthur Cook – has been recommended by so wide a variety of authors that I felt compelled to give his most famous book, He Died With His Eyes Open, a chance. It was the first in what became a series of five novels chronicling the cases of an unnamed police detective in the “Department of Unexplained Deaths” of the London Metropolitan Police.

Said detective, our narrator, is intelligent, pig-headed, hard-talking and contemptuous of authority. On the merits of his talents and police work, he ought to have been promoted several times over, but his personality, together with his open disdain for the careerism of his peers, has kept him in a dead-end job for years. But his status as a forgotten man seems to suit him, giving him more freedom to pursue his cases at his pace. Here he is, reflecting on the status of the Department of Unexplained Deaths:

The fact that [the department] is by the far the most unpopular and shunned branch of the service only goes to show that, to my way of thinking, it should have been created years ago. Trendy lefties in and out of politics or just on the edges don’t like us – but somebody has to do the job, they won’t. The uniformed people don’t like us; nor does the Criminal Investigation Department, nor does the Special Intelligence Branch. We work on obscure, unimportant, apparently irrelevant deaths of people who don’t matter and who never did. We have the lowest budget, we’re last in line for allocations, and promotion is so slow that most of us never get past the rank of sergeant. […] No murder is casual to us, and no murder is unimportant, even though murder happens the whole time in a city like this.

In the novel’s opening scene, we are introduced to one of those people “who don’t matter and never did,” the victim of a gruesome murder: Charles “Locksley Alwin Staniland, aged 51,” found in a crumpled and battered mess on the side of the road, with broken bones and a battered skull. The forensic evidence is minimal, but as our narrator-detective begins to piece together Staniland’s personal life – where he lived, what he did for a living – he comes to identify more and more with the deceased man. This process of identification becomes intensified upon the discovery of a series of Staniland’s personal cassettes, upon which he recorded some of the happenings of his daily life, as well as his thoughts and frustrations about past events. These recordings are Raymond’s most original technical improvisation, for they give the deceased man a presence in the narrative; he is not merely a nameless person to us, but possessed of a personality, dreams, and disappointments, and these facts make him sympathetic to us – and to our narrator – in a haunting way.

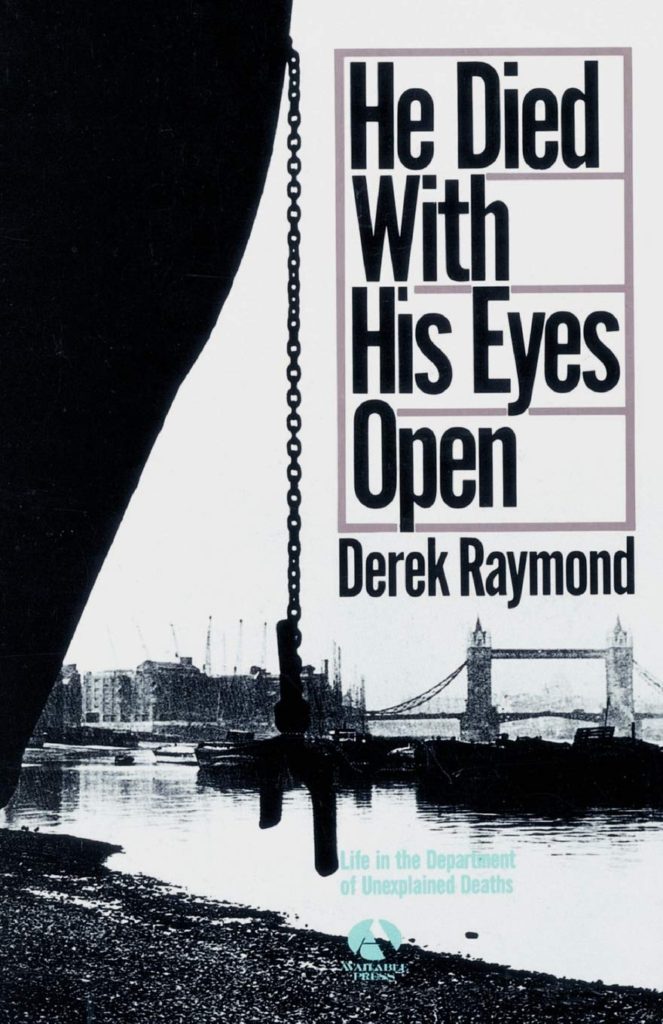

Raymond is obviously working within the conventions of detective fiction, but this is not a police procedural, and whatever tropes of the genre he employs, he rapidly abandons. This is not a book for people eager to solve a mystery or follow a Sherlock Holmes-like master detective piece together a difficult case. On the contrary, the book’s kinetic energy comes almost entirely from Raymond’s narrator-detective, whose cynicism casts all he sees – people and places alike – in the black-and-white drear of the cover image. Consider the following scene, taking place as our detective seeks to follow up on the murder victim’s financial situation:

It really is a dreadful nuisance his dying like this,’ said Staniland’s bank manager. ‘He had an eleven-hundred-pound loan account, don’t you know, and there’s the interest owing on it.’

‘An unsecured loan?’

‘Well, not quite – there are a few equities. But equities are performing miserably at the moment, as you probably know.’

‘No, I don’t own any shares,’ I said. ‘I don’t know.’

‘The bank stands to be several hundred pounds out on this affair,’ said the manager. ‘Several hundred.’

‘We’re talking about a murder.’

‘I daresay. Even so, it’s very awkward.’

It is difficult to fault a character for cynicism when the world seems so eager to affirm the correctness of the cynic. A murder becomes “an affair” and a man’s life causes a bank clerk less stress than “several hundred pounds” – awkward, indeed.

The gradual closing of the psychological distance between the murder victim and detective offers more drama than the murder mystery itself. Our unnamed detective, reflecting on his similarity with the deceased, comments: “Where I identified with Staniland, what I had inherited from him, was the question why. Mind, I had always asked it myself – but this was not a copper’s why. Staniland’s question was the question I had once read on a country gravestone erected to a child of six: ‘Since I was so early done for, I wonder what I was begun for.'” That “‘not a copper’s why” pretty brilliantly encapsulates not only our narrator’s outlook, but our author’s: this is not a book about the mechanical details of a specific murder, but the philosophical-psychological details of all murders. It is not enough for our detective to know who did the killing; he must understand the why. This is Miltonic, justify-the-ways-of-god levels of ambition. Which brings us to the title, alluded to in one of Staniland’s private recordings: “Most people live with their eyes shut, but I mean to die with mine open” – a creed that our narrator would eagerly co-sign. He Died With His Eyes Open forces that outlook on its readers as well; it compels us to view a side of British society eagerly overlooked by the upper crust, and probes, with surgical precision, the lives of the men and women living there.