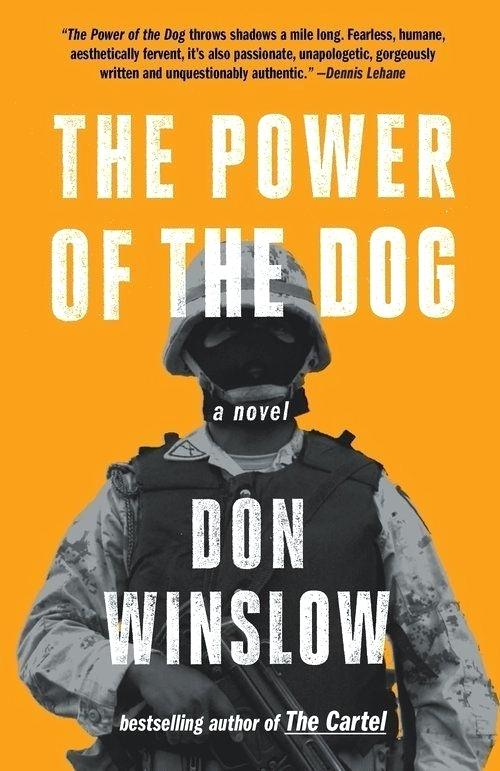

This is a book well outside my regular wheelhouse, a best-selling thriller novel, but it came up, again and again, in my readings about the decades-long debacle colloquially known as America’s “border crisis.” Drugs, sex and murder – the stock-in-trade of the thriller genre – have been in superabundance along the U.S.-Mexico border for some time now, so credit to Don Winslow for recognizing the dramatic potential of the conflict, and for doing his research: he spent some six years investigating the drug trade, probing the grim history of the CIA’s involvement in Latin America, and interviewing victims and their families. The resulting novel, The Power Of The Dog, has sold millions of copies since its release in 2005, spawned two sequels, and captured the imagination of Ridley Scott, whose production company purchased the film rights.

What immediately stands out about The Power Of The Dog is its ambition: we get not only a large cast of characters, but a plot spanning almost two decades, from 1975 to 1994. Winslow also does a magnificent job weaving his fictional narrative into the history of the so-called “war on drugs,” using actual events – the 1985 Mexico City earthquake, the assassination of Mexican president Luis Donaldo Colosio, and the infamous Operation Condor, in which the United States backed right-wing militias in a bid to prevent the spread of communism in South America – to buoy his plot. The narrative itself is told from multiple perspectives, following one or another of its characters through time. There is Arthur “Art” Keller, a Vietnam veteran turned DEA agent; Adán and Raúl Berrera, nephews of a powerful drug lord, with ambitions to expand their uncle’s reach; Nora Hayden, a beautiful prostitute whose popularity with her customers ingratiates her with the cartel bosses; Sean Callan, an Irish youth from Hell’s Kitchen who becomes a professional hitman; and Juan Ocampo Parado, a Catholic chain-smoking priest, and one of the few men in Mexico brave enough to speak out against both the government corruption and the reach of the cartels. Some of these characters are based upon real-life figures, or are clever composites. These include Benjamín Arellano Félix, one-time head of the Tijuana Cartel, who, at the height of his powers, supplied America with one-third of its cocaine; Amado Carrilo Fuentes, the “lord of the skies,” who used a fleet of cargo jets to transport his drugs; and the now-infamous Joaquín “El Chapo” Guzmán, head of the Sinaloa Cartel, whose net worth, at the time of his capture, exceeded $14 billion.

What emerges from Winslow’s narrative, again and again, is the sickening co-dependence that has evolved between the cartels and the United States government, as well as the blight of corruption and bureaucratic sclerosis that prevents any meaningful change from occurring. The absurdity of the situation deserves some comment: plants that grow on the ground like fruit in Mexico, and would otherwise be worthless, are inflated in value thanks to America’s drug laws, which do nothing to reduce the demand for the drugs but do suffice to increase their market value exponentially. South American governments, historically weak, ineffectual and corrupt, have largely failed at cultivating native industries and businesses, while the one industry operating outside their reach has grown to proportions vastly exceeding most Fortune 500 companies. The stunning wealth of the cartels enables them, in turn, to further corrupt the governments of their host countries, bribing police officers and judges, funding electoral campaigns, and threatening anyone who dares to stand in their way. The United States government has played an equally despicable role in this circus, spending untold billions to prosecute a “war on drugs” for supposedly moral reasons while simultaneously funding and providing tactical and military training to paramilitary organizations more aptly described as “death squads,” whose only mission was to suppress peasant uprisings in South America, and whose only accomplishment was to further delay the emergence of legitimate, representative government in these countries.

Winslow’s novel takes us deep into this tangled web of corruption and double-dealing, distinguishing itself from other offerings in the genre by its intricate plotting and punchy prose. I will not go so far to say that his characters have great depth or emotional complexity, but neither are they cardboard cutouts. The heroes are compromised figures, the villains never entirely unsympathetic, and all of them operate under something like fate – the recognition that the billion-dollar drug industry, whether they’re fighting for it or against it, operates with a logic of its own, and an inescapable gravitational pull.