Emil Cioran, the Romanian-born French philosopher who lived his life perpetually on the verge of suicide, seems perhaps an odd choice for a consoling figure, but that is exactly what he has become to me. The man who “provoked existence to single combat, if only to see which of us would win,” who dared an existence without illusion or comfort, and paid a heavy price for his audacity, nonetheless emerges triumphant. “In my way, I must be a fighter, since I have not succumbed to my ruminations.” He calls to mind Kafka’s advice to the despairing:

Emil Cioran, the Romanian-born French philosopher who lived his life perpetually on the verge of suicide, seems perhaps an odd choice for a consoling figure, but that is exactly what he has become to me. The man who “provoked existence to single combat, if only to see which of us would win,” who dared an existence without illusion or comfort, and paid a heavy price for his audacity, nonetheless emerges triumphant. “In my way, I must be a fighter, since I have not succumbed to my ruminations.” He calls to mind Kafka’s advice to the despairing:

Anyone who cannot cope with his life while he is alive needs one hand to ward off a little his despair over his fate… but with his other hand he can jot down what he sees among the ruins, for he sees different and more than the others; after all, he is dead in his own lifetime and the real survivor.

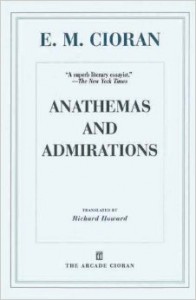

Compare this, in fact, to one of his aphorisms: “Man being an ailing animal, any of his remarks, his gestures, has symptomatic value.” This survival is Cioran’s triumph, and Anathemas And Admirations one of its products. Unlike On The Heights Of Despair and A Short History Of Decay, however, Anathemas And Admirations combines full-length essays with his customary aphorisms; extended meditations on Joseph de Maistre (whom I first encountered through Isaiah Berlin), Beckett and Fitzgerald accompany insights into more obscures figures like the Italian poet Guido Ceronetti or the Spanish philosopher Maria Zambrano (a disciple of José Ortega y Gasset).

The book proper lacks the sustained energy of its predecessors – a strange thing to say about works so full of despair, that they possess an “energy” – but it is nonetheless stamped by Cioran’s peculiar talent of adding to life via subtraction. He calls Beckett “a destroyer who adds to existence – who enriches by undermining it,” and could equally well be speaking of himself. What do we make of, for example, the following:

Overwhelming joy, if extended, is closer to madness than is the persistent melancholy which justifies itself by reflection and even by mere observation, whereas joy’s excesses derive from some derangement. If it is disconcerting to be happy over the mere fact of being alive, it is quite normal, on the other hand, to be sad even before learning baby talk.

It seems to me patently true, but the admission is fatal. His essay on F. Scott Fitzgerald amuses because it criticizes the author of The Great Gatsby for refusing to succumb to his despair, for taking refuge in self-pity (“Have no pity for those who pity themselves; they will never give way altogether…”) rather than doing the heroic thing and confronting his melancholy head on:

…he degraded this failure, stripped it of all its spiritual value. Nor should we be surprised: in the real “dark night of the soul,” he struggled more as a victim than as a hero. The same is true of all those who live their drama solely in terms of psychology; unsuited to perceiving an exterior absolute to combat or to yield to, they eternally relapse into themselves in order to vegetate, ultimately, beneath the truths they have glimpsed.

Here Cioran is chastising Fitzgerald for failing to do what he, Cioran, has spent a lifetime doing. “Like all frivolous men, he trembles at venturing further into himself. Yet a fatality impels him onward. He resists extending his being to its limits, and he reaches them in spite of himself.” Fitzgerald comes to his limits reluctantly, as healthy people do; Cioran spent a life at the limits, and his works read like reports from the abyss itself.