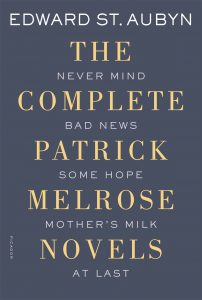

One of the staples of British fiction is the so-called “novel of manners,” which takes a magnifying glass to the customs, manners and mannerisms of a social class. Think, for example, of the works of Jane Austen, or of Thackeray’s Vanity Fair or Waugh’s Brideshead Revisited. Edward St. Aubyn’s Never Mind, the first in a quintet of autobiographical works known as The Patrick Melrose Novels, stands this tradition on its head. Staples of the genre are recognizable: a country setting, an aristocratic family, and a dinner party involving men and women of different ages and social ranks, but from the opening scene, in which a housekeeper hides from the patriarch, David Melrose, as he delights in killing a colony of ants with a garden hose, St. Aubyn puts the reader on edge. This first novel in the series takes place over the course of a single day, when the titular Patrick Melrose is only a child, some five years old, and so it is his parents who take center stage, who get the most lines and the fleshed out backstories, but it is Patrick who wins our sympathy, for by novel’s end, David Melrose will bend his young son over his marriage bed and rape him.

One of the staples of British fiction is the so-called “novel of manners,” which takes a magnifying glass to the customs, manners and mannerisms of a social class. Think, for example, of the works of Jane Austen, or of Thackeray’s Vanity Fair or Waugh’s Brideshead Revisited. Edward St. Aubyn’s Never Mind, the first in a quintet of autobiographical works known as The Patrick Melrose Novels, stands this tradition on its head. Staples of the genre are recognizable: a country setting, an aristocratic family, and a dinner party involving men and women of different ages and social ranks, but from the opening scene, in which a housekeeper hides from the patriarch, David Melrose, as he delights in killing a colony of ants with a garden hose, St. Aubyn puts the reader on edge. This first novel in the series takes place over the course of a single day, when the titular Patrick Melrose is only a child, some five years old, and so it is his parents who take center stage, who get the most lines and the fleshed out backstories, but it is Patrick who wins our sympathy, for by novel’s end, David Melrose will bend his young son over his marriage bed and rape him.

St. Aubyn employs third-person narration throughout the series, giving us multiple perspectives on his various characters: their own, of course, but also the opinions of spouses, children, friends and acquaintances. And the first thing we learn about his characters, from such a variety of views, is that no one likes anyone else, and the more closely two people are related, the lower their likely opinions of one another. Here, for example, is Eleanor Melrose, David’s wife, reflecting on her husband:

When she had first met David twelve years ago, she had been fascinated by his looks. The expression that men feel entitled to wear when they stare out of a cold English drawing room onto their own land had grown stubborn over five centuries and perfected itself in David’s face. It was never quite clear to Eleanor why the English thought it was so distinguished to have done nothing for a long time in the same place, but David left her in no doubt that they did. He was also descended from Charles II through a prostitute.

We learn an awful lot about David Melrose in this short, pithy description. He’s imperious, with aristocratic pretensions, but also largely unaccomplished, and his noble lineage – such as he can claim it – runs through a prostitute. Astute readers will also recognize that the reference to Charles II is not accidental; he was a notorious philanderer, prompting John Dryden to quip that he “scattered his maker’s image throughout the land.” Eleanor is American, and, we will later learn, descended from wealth:

When she had met David, she thought that he was the first person who really understood her. Now he was the last person she would go to for understanding. It was hard to explain this change and she tried to resist the temptation of thinking that he had been waiting all along for her money to subsidize his fantasies of how he deserved to live. Perhaps, on the contrary, it was her money that had cheapened him. He had stopped his medical practice soon after their marriage. At the beginning, there had been talk of using some of her money to start a home for alcoholics. In a sense they had succeeded.

The perfect marriage: British nobility with American money – another commonplace of English fiction, but this nightmarish pairing of sadist and masochist has no precedent I’m aware of. Immediately on the heels of Eleanor’s reminiscences, we get an equivalent recollection from David, of a time, early in their courtship, when he cooked her a meal of stuffed pigeon and then bade her eat it off the floor, like a dog, without using her hands. “She knelt down on all fours on the threadbare Persian rug, her hands flattened either side of the plate. Her elbows jutted out as she lowered herself and picked up a piece of pigeon between her teeth. She felt the strain at the base of her spine.” Voluntarily forfeit your own self-respect and you will never recover it, at least not in the eyes of your tormentor; Eleanor pays dearly for her gesture of obedience.

We first meet Patrick on the estate grounds, where he is playing, by himself, near a well; St. Aubyn, it seems, is fond of thematic imagery: “He was forbidden to play by the well. It was his favourite place to play. Sometimes he climbed onto the rotten cover and jumped up and down, pretending it was a trampoline. Nobody could stop him, nor did they often try.” Having already been introduced to his parents, we’re scarcely surprised that the young Patrick is so often left alone – we might even be grateful for that – and the image of a young boy carelessly jumping over an abyss seems tragically appropriate, particularly in retrospect, for he is destined to take a plunge. When he returns to his home, we are treated to his own observations about his father, no less perceptive than his mother’s:

He had watched his father’s eyes behind their dark glasses. They moved from object to object and person to person, pausing for a moment on each and seeming to steal something vital from them, with a quick adhesive glance, like the flickering of a gecko’s tongue.

Vivid images, such as that gecko’s flickering tongue, can be found on every page, conveyed in prose polished by years of effort and leavened by the sharpest (and darkest) sense of humour I’ve encountered in contemporary fiction. I began this review by describing these novels as autobiographical. Edward St. Aubyn, like his fictional counterpart, was indeed raped by his father, and spent the better part of his youth and young adulthood numbing himself with heroin. In his telling, these novels were an effort to make sense of that pain. Of that, I cannot judge. But as a novel, Never Mind is witty and humane, and amply compensates the reader for the experience of its darkness.