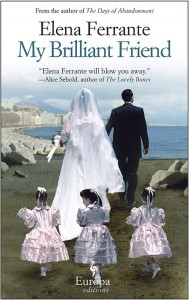

No book or series of books has been more frequently recommended to me than Elena Ferrante’s tetralogy of Neapolitan novels, and the best compliment I can give those friends who thrust her on me is that, immediately upon finishing My Brilliant Friend, I found myself in a bookstore buying the sequel. The series has become a literary sensation, selling out all over the world and inspiring profuse praise from writers and critics alike, but the author is something of a mystery: “Elena Ferrante” is a pseudonym. The real writer is known only to her publishers, having declined the spotlight for allegedly personal reasons. This reticence stands in stark contrast to the confessional, personal tone of her novels: My Brilliant Friend is narrated by a young woman, Elena Greco, who is writing in the present, conjuring up her childhood in 1950s Naples, because her lifelong best friend Rafaella Cerullo (Lina to her friends, Lila to Elena) has gone missing. After less than ten pages of the present, Ferrante thrusts us into the past, and the complicated combination of time and place that forged so powerful a bond between two young women.

No book or series of books has been more frequently recommended to me than Elena Ferrante’s tetralogy of Neapolitan novels, and the best compliment I can give those friends who thrust her on me is that, immediately upon finishing My Brilliant Friend, I found myself in a bookstore buying the sequel. The series has become a literary sensation, selling out all over the world and inspiring profuse praise from writers and critics alike, but the author is something of a mystery: “Elena Ferrante” is a pseudonym. The real writer is known only to her publishers, having declined the spotlight for allegedly personal reasons. This reticence stands in stark contrast to the confessional, personal tone of her novels: My Brilliant Friend is narrated by a young woman, Elena Greco, who is writing in the present, conjuring up her childhood in 1950s Naples, because her lifelong best friend Rafaella Cerullo (Lina to her friends, Lila to Elena) has gone missing. After less than ten pages of the present, Ferrante thrusts us into the past, and the complicated combination of time and place that forged so powerful a bond between two young women.

Naples in the 1950s is chaotic, caught between the horrors of the past and the uncertainties of the future, and much of Ferrante’s genius lies in how artfully she evokes this setting. The first thing the narrator tells us is that it was “full of violence,” and we quickly learn the truth of that statement. Husbands beat their wives, parents beat their children, and public assaults and even murder happen with alarming frequency. “Life was like that,” Greco tells us, “that’s all, we grew up with the duty to make it difficult for others before they made it difficult for us.” Everywhere there is tension. The tiny neighborhood in which she grows up, in which everyone knows everyone else, contains poor families and wealthy families, unhappy marriages, unfaithful spouses and intergenerational conflict. The impression the reader gets, the impression Elena gradually has herself, is a terrible sense of belatedness, as if all the relevant events have already happened, the decisions all already been made, and the people of the neighborhood – including the very young – must grow up only to live out those consequences. Elena’s best friend Lila is the first to understand this:

Thus she returned to the theme of “before,” but in a different way than she had at first. She said that we didn’t know anything, either as children or now, that we were therefore not in a position to understand anything, that everything in the neighborhood, every stone or piece of wood, everything, anything you could name, was already there before us, but we had grown up without realizing it, without ever even thinking about it. Not just us. Her father pretended that there had been nothing before. Her mother did the same, my mother, my father, even Rino. […] They didn’t know anything, they wouldn’t talk about anything. Not Fascism, not the king. No injustice, no oppression, no exploitation.

This is Italy after World War II, after fascism, after its complicity in some of history’s worst atrocities. This is the terrible burden the young feel, the disconnect between how they are expected to live their lives and how the shrinking world – with radio and television and international fashion magazines – suggests life ought to be lived. This is Ferrante’s setting, seen through the eyes of a child, and it is masterfully presented to us, as comprehensively and believably portrayed as Joyce’s Dublin or Dickens’ London. The class tensions are palpable. Elena is the daughter of a working class family, as is Lila, but both will gradually explore the world outside their little neighborhood and discover the existence of wealth and luxury, and the lucky few who possess them. Here she is describing her first experience in a wealthier area:

It was like crossing a border. I remember a dense crowd and a sort of humiliating difference. I looked not at the boys but at the girls, the women: they were absolutely different from us. They seemed to have breathed another air, to have eaten other food, to have dressed on some other planet, to have learned to walk on wisps of the wind. I was astonished. All the more so that, while I would have paused to examine at leisure dresses, shoes, the style of glasses if they wore glasses, they passed by without seeming to see me. They didn’t see any of the five of us. We were not perceptible. Or not interesting. And in fact if at times their gaze fell on us, they immediately turned in another direction, as if irritated. They looked only at each other.

The pain of this perceived inferiority and the desire for material gain drives many of the characters in the novel, the men as well as the women, and often to painful or self-defeating decisions, but this is not the novel’s true subject.

What animates My Brilliant Friend, what gives it its irresistible quality as fiction, is its portrayal of the budding friendship between the narrator, Elena, and her best friend and lifelong companion, Lila. For as much love and compassion as the two possess for one another, there is also bitter jealousy, a rivalry that provokes both to challenge and change themselves in accordance with the qualities of the other. Much has already been written of this portrayal, and how it is supposedly representative of the female friendship dynamic (Emily Gould called it “The truest evocation of a complex and lifelong friendship between women I’ve ever read”), and though I am ill-placed to comment on this, I can’t help but feel astonished at the complexity and, well, difficulty of the friendship. Lila represents, to Elena, the eternal benchmark by which she will judge her life, and so she is as often a source of anxiety, pain and defeat as she is of consolation and comfort. When Lila triumphs, Elena feels inferior, dejected; when Lila seems lost or out of place, Elena finds new meaning in her own pursuits. “It was as if, because of an evil spell, the joy or sorrow of one required the sorrow or joy of the other; even our physical aspect, it seemed to me, shared in that swing.” In an interview with Vanity Fair, Ferrante had this to say about friendship, and female friendships in particular:

Friendship is a crucible of positive and negative feelings that are in a permanent state of ebullition. There’s an expression: with friends God is watching me, with enemies I watch myself. In the end, an enemy is the fruit of an oversimplification of human complexity: the inimical relationship is always clear, I know that I have to protect myself, I have to attack. On the other hand, God only knows what goes on in the mind of a friend. Absolute trust and strong affections harbor rancor, trickery, and betrayal. Perhaps that’s why, over time, male friendship has developed a rigorous code of conduct. The pious respect for its internal laws and the serious consequences that come from violating them have a long tradition in fiction. Our friendships [women’s friendships], on the other hand, are a terra incognita, chiefly to ourselves, a land without fixed rules. Anything and everything can happen to you, nothing is certain. Its exploration in fiction advances arduously, it is a gamble, a strenuous undertaking. And at every step there is above all the risk that a story’s honesty will be clouded by good intentions, hypocritical calculations, or ideologies that exalt sisterhood in ways that are often nauseating.

It is exactly that dynamic of “rancor, trickery, and betrayal” existing alongside trust, compassion and affection that makes the friendship between Elena and Lila so compelling, and Ferrante’s refusal to “exalt sisterhood,” her unwillingness to flinch from an honest portrayal of even its most unflattering aspects and instead to surgically probe and anatomize every eruption of jealousy and distrust, that makes this novel so unique a character study. The title itself speaks to this strange dynamic: we, as readers, are led to believe that it is Lila who is the “brilliant friend,” the preternaturally gifted student who earns the admiration of her teachers without effort, who devotes herself to reading Tolstoy and Dostoevsky, whose budding beauty captures the attentions of all of the men in Naples. But the phrase “my brilliant friend” appears only once in the novel, and it is Lila who speaks it of Elena.

Their friendship is of such an intense quality that no man, no love interest, can possibly hope to compete. Both characters say as much, explicitly. Add to that the deep admiration they share for one another, and something sapphic seeps into the relationship, a quality of love so intense that it crowds out, even displaces, what love they have for men. Is this, also, a quality to be found in the closest female relationships? Perhaps it is better, as a man, not to know.

My Brilliant Friend is a triumph, as good a modern novel as I have read, and finishing the series has quickly become one of this year’s highest priorities.