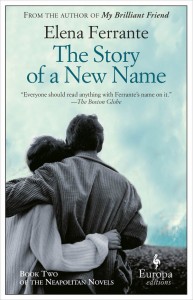

The Story Of A New Name, the second book in Elena Ferrante’s Neapolitan series, picks up almost immediately where the first one let off, thrusting readers back into the drama of post-World War II Italy and the strained friendship of Elena Greco and Raffaella “Lina” Cerullo. From this point onward, I will be discussing the plot in some detail, so new readers of the series should beware.

The Story Of A New Name, the second book in Elena Ferrante’s Neapolitan series, picks up almost immediately where the first one let off, thrusting readers back into the drama of post-World War II Italy and the strained friendship of Elena Greco and Raffaella “Lina” Cerullo. From this point onward, I will be discussing the plot in some detail, so new readers of the series should beware.

The penultimate dramatic moment of the first book in the series involved Lina’s marriage to Stefano Carracci, the son of a notorious black market dealer and loan shark. The match enriches Lina’s family, as the Cerullos and the Caraccis join forces in marketing high-end shoes originally designed by Lina, but tensions, only hinted at in the first book, quickly shatter the marriage. Here, for example, is Elena’s description of Lina on her honeymoon:

What have I done, she thought, dazed by wine, and what is this gold circle, this glittering zero I’ve stuck my finger in. Stefano had one, too, and it shone amid the black hairs, hairy fingers, as the books said. She remembered him in his bathing suit, as she had seen him at the beach. The broad chest, the large kneecaps, like overturned pots. There was not the smallest detail that, once recalled, revealed to her any charm. He was a being, now, with whom she felt she could share nothing and yet there he was.

Her ring, the most potent symbol of a marriage, is a “glittering zero,” and her husband’s kneecaps are unromantically described as “overturned pots.” Small wonder, then, that she resists his attempts to consummate the marriage, and contemplates “stealing a knife from the table to stick in his throat” to keep him at bay. What she does not give willingly, her husband takes by force (“What are you doing, be quiet, you’re just a twig, if I want to break you I’ll break you”), and thus does Lina have her first taste of sex and marriage, and the “new name,” her husband’s name, the title alludes to.

Lina is herself a bit of a cypher, a woman whose beauty and intelligence captivates the entire neighborhood, but whose motivations are poorly intuited by everyone around her, with sometime tragic, sometime comic results. She is victimized, often brutally, by her husband, who seeks to control her and treats her more like an ornament to his success rather than a human being, but she resists his control and is capable of matching and even exceeding his destructive power. “She knew how to set the nerves of good people alight,” says Elena; “in their breasts she kindled the fire of destruction.” Elena, by contrast, is too filled with self-doubt and timidity, she laments her “tendency to conceal” herself, and these contrasts are brought to a conflict through the figure of Nino Sarratore, whom both women fall in love with. It is Lina, foremost in all things, who wins Nino’s heart, and their affair and the subsequent fallout as Lina’s marriage collapses serves to provoke meditations on the nature of men and women, of sex and love. There is, for example, the violent, domineering ideal of manhood exhibited by the Carraccis and Solaras. Here, for example, is the narrator’s description of Stefano’s attitude towards his wife: she speaks of “an order that was coming to him from very far away, perhaps even from before he was born. The order was: be a man, Ste’; either you subdue her now or you’ll never subdue her; your wife has to learn right away that she is the female and you’re the male and therefore she has to obey.” But the terrible physical damage men can inflict, the menace their strength represents, has a corresponding impotence as well. Stefano is powerless to control his wife, to bend her to his will, and Lina learns early on the powers of charm and attraction, and the influence this understanding grants her:

To my great amazement, […] she behaved like a woman who knows what men are, who has nothing more to learn on the subject and in fact would have much to teach: and she wasn’t playing a part, the way we had as girls, imitating novels in which fallen ladies appeared; rather, it was clear that her knowledge was true, and this did not embarrass her.

When Lina wins Nino’s heart, it is this very power of hers that causes Elena to question her motives, to be uncertain of the genuineness of Lina’s feelings. When she confronts her about this, Lina replies in terms that both confirm and deny Elena’s suspicions:

She said I ought to be proud of her, she had made me look good. Why? Because she had been considered in every way finer than the very fine daughter of my professor. because the smartest boy in my school and maybe in Naples and maybe in Italy and maybe in the world – according to what I said, naturally – had just left that very respectable young lady, no less, to please her, the daughter of a shoemaker, elementary-school diploma, wife of Carracci. She spoke with increasing sarcasm and as if she were finally revealing a cruel plan of revenge.

The tone of sarcasm Lina adopts suggests that she is mocking her friend’s suspicions, that she is not really ruining two relationships – among them her marriage – for a boost in self-esteem. And yet her very perception, her ability to intuit Elena’s suspicions so precisely, suggests that these reasons, so reminiscent of her husband’s superficial interest in her, had nonetheless occurred to her.

No living author I am familiar with has so completely dissected the complicated mix of admiration and envy, push and pull, that attend the closest friendships and family relationships, and no fictional portrait of friendship better exemplifies these contradictory qualities than that of Elena and Lina.