After David Foster Wallace’s death in 2008, a large chunk of his personal library – together with his notes, manuscripts and correspondence – was purchased by the University of Texas, where it can still be perused. And among those volumes of Kafka and DeLillo and Pynchon – all heavily annotated – are equally marked up works of what can only be called “self-help” books: pop psychology books on managing depression or reconciling with inadequate parents or grappling with creativity. Some fans professed difficulty reconciling the popular image of Wallace as a genius with their image of someone who reads the latest Oprah-approved bestseller – was this yet another one of his idiosyncrasies? or a desperate attempt to manage his depression?

After David Foster Wallace’s death in 2008, a large chunk of his personal library – together with his notes, manuscripts and correspondence – was purchased by the University of Texas, where it can still be perused. And among those volumes of Kafka and DeLillo and Pynchon – all heavily annotated – are equally marked up works of what can only be called “self-help” books: pop psychology books on managing depression or reconciling with inadequate parents or grappling with creativity. Some fans professed difficulty reconciling the popular image of Wallace as a genius with their image of someone who reads the latest Oprah-approved bestseller – was this yet another one of his idiosyncrasies? or a desperate attempt to manage his depression?

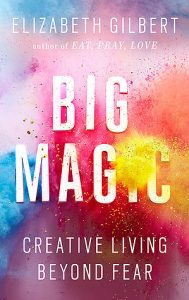

There are, to borrow a distinction made by Elizabeth Gilbert, generally two types of writers: those who view writing as a gift, and those who view it as a burden. In the latter camp are Philip Roth, Norman Mailer, F. Scott Fitzgerald, Hemingway and a half-dozen others who spent as much time drinking or lamenting their fate as actually writing. A familiar Hemingway quote is illustrative: “There is nothing to writing. All you do is sit down at a typewriter and bleed.” Thomas Mann, in a similar expression of anguish, said that “a writer is someone for whom writing is more difficult than it is for other people.” Elizabeth Gilbert is decidedly not of that camp, and in Big Magic she makes a case for a different approach to creativity, one that views it as a talent to be nurtured rather than as a curse to be withstood. Easier said than done, perhaps, but a great many writers – and untold numbers of aspiring writers – have suffered immensely for their inability to embrace their passion. Gilbert shares one illustrative example, of an ex-boyfriend whose tastes in literature were so refined, whose imagination was so lofty, that he “didn’t want to sully the dazzling ideal that existed in his mind by putting a clumsy rendition of it down on paper.” He, of course, remains a total unknown, whereas Gilbert has spent a year atop the New York Times bestseller list. “He felt there was nobility in his choice never to write a book, if it could not be a great book.” If that seems stupid, it’s because it is, and yet I and no doubt many others are guilty of this exact mental mistake.

In Big Magic, Gilbert flips the image of the tortured artist around: “An abiding stereotype of creativity is that it turns people crazy. I disagree: Not expressing creativity turns people crazy.” She then goes on to quote a lovely passage from the Gospel of Thomas: “If you bring forth what is within you, what you bring forth will save you. If you don’t bring forth what is within you, what you don’t bring forth will destroy you.” Kafka, in his diaries, expressed a sentiment Gilbert would agree with: “A non-writing writer is a monster courting insanity.” (Though, it should be said, that anyone who reads Kafka’s diaries will not leave them with the impression that writing is a fun or affirming hobby.)

It’s easy to be cynical about this kind of work – and I was, certainly, before I read it – but the truth is that any artistically demanding endeavour, be it writing or painting or songwriting, demands such sustained effort and concentration, such a marshalling of spirit and a risking of self-esteem, that the lessons of Big Magic become not only helpful but necessary, at least if you want to avoid the alcohol and the early grave.