The 21st century began poorly for those who care about liberty. The September 11th attacks ushered in an era of paranoia and fear marked by warrantless wiretapping, indefinite detention and a state of near-permanent war. Worse still, cynical opportunists in the guise of politicians have so reconstituted our language that to be patriotic means to acquiesce without dissent, and the pursuit of freedom now entails the suspension of habeas corpus and the rights of the accused. The apathy of the public who suffer these depredations seems limitless. The revelation that our own governments are spying on us with impunity raises less concern than the gyrations of Miley Cyrus. The major American political parties, devoted though they are to publicly feuding over their differences, are united in their disdain for civil liberties. It is difficult even to discuss freedom or liberty without irony, so corrupted have these words become, so abstracted from their true meanings and concrete referents, but those who sneer must still confront Guantanamo, must at some time acknowledge their tacit approval of a government that locks up even children without formal charges or legal recourse.

The 21st century began poorly for those who care about liberty. The September 11th attacks ushered in an era of paranoia and fear marked by warrantless wiretapping, indefinite detention and a state of near-permanent war. Worse still, cynical opportunists in the guise of politicians have so reconstituted our language that to be patriotic means to acquiesce without dissent, and the pursuit of freedom now entails the suspension of habeas corpus and the rights of the accused. The apathy of the public who suffer these depredations seems limitless. The revelation that our own governments are spying on us with impunity raises less concern than the gyrations of Miley Cyrus. The major American political parties, devoted though they are to publicly feuding over their differences, are united in their disdain for civil liberties. It is difficult even to discuss freedom or liberty without irony, so corrupted have these words become, so abstracted from their true meanings and concrete referents, but those who sneer must still confront Guantanamo, must at some time acknowledge their tacit approval of a government that locks up even children without formal charges or legal recourse.

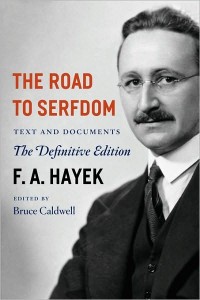

The Road To Serfdom, published in the dying years of World War II, was from the first steeped in controversy, the reason for which is best encapsulated by the book’s dedication “To the socialists of both parties.” Part of Hayek’s thesis is not merely that fascism and communism have in common more than had been generally understood, but that the groundwork for fascism in Germany – and the potential for it in Britain – was laid by those who would seek to place the economy under state control. Far better, Hayek argues, to submit to an impartial economic system that maximizes the freedom of its participants to work how they please, in what industry they please, for as long or as hard as they please, and to enter into whatever economic arrangements they see fit, at the expense of gross disparities between the winners and losers, than to bequeath to anyone the power necessary to produce specific results such as the elevation of a once-oppressed minority group or the diminution of income inequality. Hayek writes,

Who can seriously doubt that a member of a small racial or religious minority will be freer with no property so long as fellow-members of his community have property and are therefore able to employ him, than he would be if private property were abolished and he became owner of a nominal share in the community property? Or that the power which a multiple millionaire, who may be my neighbor and perhaps my employer, has over me is very much less than that which the smallest fonctionnaire possesses who wields the coercive power of the state and on whose discretion it depends whether and how I am to be allowed to live or work? And who will deny that a world in which the wealthy are powerful is still a better world than one in which only the already powerful can acquire wealth?

It is not, I trust, difficult to see in his words a continuing relevance to our current political climate. Phrases like “income inequality” and a general resentment of the wealthy – “class warfare” to the right and “social justice” to the left – have predominated since the 2008 financial crisis, and my greatest delight in reading Hayek is in the challenge he offers to both parties. If income inequality is, as he insists, a necessary byproduct of a free society, there is nonetheless no incompatibility between this freedom and, for example, universal healthcare or a social safety net. Indeed, Hayek argues that a truly wealthy society might be obligated to provide such minimum levels of care for its citizens. Nor does he envision government as simply an ineffectual entity destined to rob its citizens of their liberties (as many of the hardline libertarians of today insist) but views them as having a role to play in preventing monopolies, punishing fraud and, most astoundingly, enacting legislation that protects the environment – provided none of the above are used to favor some groups or handicap others.

The scope of Hayek’s work is remarkable, encompassing not only economic arguments but philosophical ones as well. His description of a collectivist society, for example, is unnervingly comparable to my home province of Quebec: a bloated bureaucracy that stifles competition and rewards conformity; a working class that values security and government pensions over innovation and self-employment; a muzzling of dissenting opinions leading to a political stagnation and a status quo of unceasing corruption. This is a work worthy of its reputation, a necessary challenge to the unbridled optimism and arrogance of those who believe they can manipulate without consequence something as complicated as a nation’s economy, and a reminder to the rest of us how precious is our heritage of liberty.