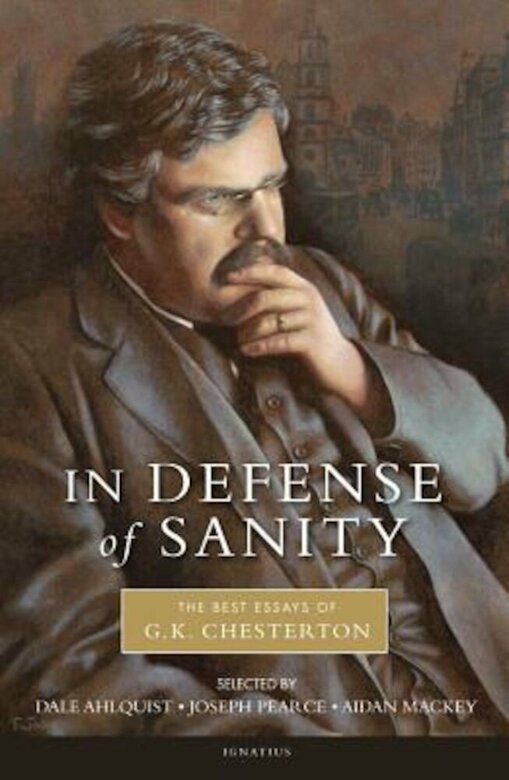

Sanity is today in short supply. The shortage makes itself visible in the men and women we elect to high office, as well as in the media class charged with reporting on them. It’s increasingly visible in our universities, supposed bastions of reason and higher thought, whose tuition has increased in indirect proportion to the amount of knowledge they impart. And finally, and most fatally, it is visible in the average man and woman, whose conduct today, in matters great and small, would seem utterly incomprehensible to generations of their ancestors. Sanity, it now seems to me, is not the default condition of mankind, but a hard-won reprieve from the status quo. G.K. Chesterton, English essayist, novelist and famous wit, never chose the title “In Defense of Sanity” for his selected essays, but it is a fitting one, for against the fashions of his age – whose consequences have come to fruition in mine – Chesterton mobilized his mind and his considerable literary talent: hundreds of poems and short stories, some 80 books, and an astonishing 4,000 essays.

The popular image of a man standing against the momentum of his time is a crank, an angry, slightly unhinged person, gawked at but never taken seriously. Chesterton explodes that stereotype. In the defence of tradition, he is witty and thoughtful and so rhetorically deft that he manages to puncture the air of inevitability that surrounded – and continues to surround – the arguments for “progress,” often with a single sentence. “For though to-day is always to-day and the moment is always modern,” he writes in “On Turnpikes and Medievalism,” taking issue with the use of “medieval” as a term of abuse, “we are the only men in all history who fell back upon bragging about the mere fact that to-day is not yesterday.” For Chesterton, it is not sufficient to label an idea or practice antiquated, traditional, or outdated in the absence of an actual argument.

In the matter of reforming things, as distinct from deforming them, there is one plain and simple principle; a principle which will probably be called a paradox. There exists in such a case a certain institution or law; let us say, for the sake of simplicity, a fence or gate erected across a road. The more modern type of reformer goes gaily up to it and says, “I don’t see the use of this; let us clear it away.” To which the more intelligent type of reformer will do well to answer: “If you don’t see the use of it, I certainly won’t let you clear it away. Go away and think. Then, when you can come back and tell me that you do see the use of it, I may allow you to destroy it.”

The story of the last 50 years of social change has too often involved not reformation but deformation, led by men and women not only unaware of the historical role played by the practices they were so casually discarding, but proud of their ignorance. But is not only the grand political and social changes that interest him; Chesterton is no less perceptive or prophetic on smaller matters, as with the changing architecture of London: “The London churches do preserve a certain historic character of London; they do remind us of a typical passage in the history of England. But the merely commercial life of England becomes less and less English; and the material machinery of London is looking more and more like New York.” If that was true in 1928, when it was written, it is far more true today, when the London skyline has been defaced by monstrosities of glass and steel, monuments to global capitalism that fit in everywhere and belong nowhere.

But Chesterton is much more than a thoughtful conservative or stalwart reactionary, and if he continues to draw an appreciative readership, it is no less for the style of his writing than the substance of his thoughts. These essays, from the opening sentence, are captivating, in the truest sense: they compel our attention through lengthy, discursive arguments and unexpected imaginative turns. One memorable essay, “What I Found in My Pocket,” describes exactly what you’d expect: the writer’s turning out his pockets – but every object occasions a deeper thought, a broader philosophical meditation. “The next thing I found was a piece of chalk; and I saw in it all the art and all the frescoes of the world. The next was a coin of a very modest value; and I saw in it not only the image and superscription of our own Caesar, but all government and order since the world began.” Be assured that anyone capable of entertaining himself, with no more than the contents of his pockets, will provide endless good fun for his readers when his mind is set loose on the wider issues of the day.