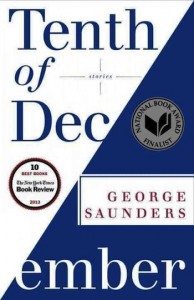

George Saunders’ latest short story collection Tenth of December was released early last year, to the kind of critical acclaim – “The best book you’ll read this year,” fawned a NYT critic in January – that inflates egos and bank accounts, and turns a humble, self-deprecating short story writer into a Franzen-like literary behemoth. I opted to wait for the paperback edition, released almost exactly a year later, and for that I am grateful because it enlarged the interval between the reading of this and one of his earlier collections, In Persuasion Nation. There is, you see, a pattern emerging in Saunders’ writing, one that, with each subsequent collection, feels increasingly derivative, increasingly safe, as if this very talented writer is contenting himself by exploring the same old ground.

George Saunders’ latest short story collection Tenth of December was released early last year, to the kind of critical acclaim – “The best book you’ll read this year,” fawned a NYT critic in January – that inflates egos and bank accounts, and turns a humble, self-deprecating short story writer into a Franzen-like literary behemoth. I opted to wait for the paperback edition, released almost exactly a year later, and for that I am grateful because it enlarged the interval between the reading of this and one of his earlier collections, In Persuasion Nation. There is, you see, a pattern emerging in Saunders’ writing, one that, with each subsequent collection, feels increasingly derivative, increasingly safe, as if this very talented writer is contenting himself by exploring the same old ground.

Don’t get me wrong: this is a very good book, one any writer would be proud to have written. Saunders’ stories are finely crafted, expertly paced, simultaneously funny and tragic and, at times, uncomfortably real. He gives voice to the voiceless, the downtrodden, the disaffected. His characters are fat, or ugly, or poor, fathers struggling to provide for their families, good people struggling not to be bad or bad people struggling to be good, and it is to Saunders’ eternal credit that he can treat each with dignity. He never positions himself (and therefore his reader) above his characters but wrings sympathy and compassion for their plights, typically by placing them in extraordinary circumstances. In the same story that he presents a teenage girl menaced by a rapist, and her teenage neighbor struggling with the decision to intervene or not, he tasks our sympathies by putting us in the mind of the assailant. In another, he contrasts the youthful innocence of a fat young boy retreating into his imagination, where he’s managed to capture the affections of a girl who in real life does not know his name, with an older man seeking to commit suicide, but in such a way that his insurance company is left none the wiser. His chosen method? Sitting in the snow until he freezes to death.

In an interview with David Sedaris appended to the back of my edition, Saunders himself describes his process: “I’m not subtle. To make ‘threat’ and thereby ‘drama’ I will just – you know, create a kindergarten teacher and then introduce an approaching Mongol horde. In the midst of a crisis is where we get the true measure of a character, and thus some new feeling about human tendency.” But Tenth of December feels like solidly trodden ground. His skills have long ago outpaced his ambitions. I can only hope that the novel he is currently working on challenges him beyond his comfort zone.