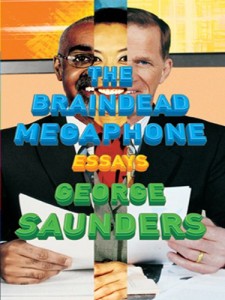

George Saunders’ The Braindead Megaphone is a collection of (largely) non-fiction essays collected from publications like GQ and The New Yorker. This is Saunders’ first non-fiction collection, but I doubt it will be his last: the formula is to take work for which an author has already been paid, repackage it in book form and reap the rewards. When a fiction writer pens a successful novel or, in Saunders’ case, work of short stories, his previous work becomes instantly more valuable, and publishers capitalize on this temporary spike in interest. The result, evidenced by this collection, is inconsistency.

George Saunders’ The Braindead Megaphone is a collection of (largely) non-fiction essays collected from publications like GQ and The New Yorker. This is Saunders’ first non-fiction collection, but I doubt it will be his last: the formula is to take work for which an author has already been paid, repackage it in book form and reap the rewards. When a fiction writer pens a successful novel or, in Saunders’ case, work of short stories, his previous work becomes instantly more valuable, and publishers capitalize on this temporary spike in interest. The result, evidenced by this collection, is inconsistency.

Alas, for all Saunders’ talents, some of these pieces feel rushed or incomplete. The eponymous essay “The Braindead Megaphone” describes American culture and media in unflattering terms, asking us to picture a man at a party holding a megaphone and the impact his unending chatter would have on our thought processes and ability to respond to his statements, or even just the fact that it would be to him rather than, say, his more soft-spoken, more intelligent counterpart in another corner of the party. Our responses, Saunders insists, “are predicated not on his intelligence, his unique experience of the world, his powers of contemplation, or his ability with language, but on the volume and omnipresence of his narrating voice.” Saunders’ point is well made and lucidly expressed, but it doesn’t achieve the kind of complexity or nuance he manages to squeeze out of his short stories. The entire essay is easily condensed into a statement that it is unlikely anyone taking the time to read his essay will have any quarrel with: we are bombarded by a sensationalist media and entertainment that is gradually dulling our receptivity to real thought and pacifying us when we should be most provoked. Every single story in In Persuasion Nation treats of that same subject with greater force.

Things take a turn for the worse with “The New Mecca,” an essay chronicling the author’s experiences on a trip to Dubai for which GQ covered his expenditures. Once again, the writing is characteristically funny and Saunders manages to find moments of genuine human feeling within the Disney Land-like playground that is Dubai’s resorts, but as to the nagging guilt of enjoying such wealth and pleasure in the middle of a desert surrounded by poverty and illiteracy, he can only retreat into a moral calculus that seems more cowardly than admirable: sure these resort employees work 16-hour days for less than minimum wage, but boy are they happy to have those jobs when the alternative is unemployment and starvation elsewhere. One gets the sense that GQ‘s largesse in footing the bill was contingent on Saunders taking a less-than-critical perspective in his essay.

The personal essays, however, better demonstrate what he is capable of in the essay form. An analysis of a Donald Barthelme short story that ends up being as impressively conceived as the story itself, and a treatise on Kurt Vonnegut and his influence on Saunders’ development as a writer becomes a meditation on the powers of fiction and how these powers are best accessed. I have read interviews and essays by quite a few famous writers on the actual process of writing and only Zadie Smith manages to communicate the difficulties of the task with Saunders’ earnestness and ease – possibly, I’m convinced, because neither of them seem to truly believe they are deserving of the acclaim they have received.

My favorite piece deals with the American immigration “crisis” and finds Saunders patrolling a Texas ranch with a privately-formed, heavily-armed militia, composed not of illiterate rednecks and racists but earnest men and women of seemingly above-average intelligence, out for the adventure and camaraderie as much as the desire to prevent illegal immigration. He attends a protest rally (more racism and spectacle here, though one man of Hispanic descent loudly proclaims that he is not a “Mexican-American” but an “American” opposed to illegal immigration), visits with a church that gives succor to illegal immigrants who cannot afford healthcare, and sits down for a meal with the “Minute Men,” vocal proponents of wall-building and zero-tolerance policies. But even here Saunders is surprised to find not caricatures but human beings, people who do not dismiss him as a “left coast liberal” but engage with him and take his arguments into consideration. It is a heartfelt piece that does a much better job managing ambiguity and irresolution than the piece on Dubai.

This collection is not destined for canonization like David Foster Wallace’s Consider The Lobster or A Supposedly Fun Thing I’ll Never Do Again, and I suppose much of my disappointment stems from the hope that it would rise to those heights. But it is an excellent companion piece to Saunders’ short fiction, sharing their hallmark humor and poignancy.