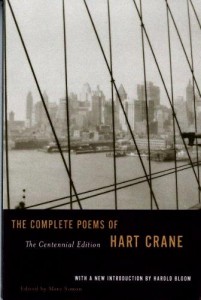

Harold Hart Crane was born in 1899 and took his own life, 32 years later, by throwing himself into the Atlantic ocean. We will never know the magnitude of the loss we suffered by his early death, but he is invoked in the same breath as Keats and Isaak Babel as great literary what-ifs. For my part, I have known of Crane since I was a teenager: he was the earliest love of the literary critic Harold Bloom, who was just two years old when Crane killed himself. Bloom discovered Crane in a Brooklyn library when he was only ten years old, taking out the book so often that he had the entirety of his verse, some 200 pages in my edition, memorized by the time he was twenty years old. It was also Bloom, among a small handful of other prescient literary critics, who first championed Crane’s genius, and so it is fitting that my centennial edition begins with an introduction supplied by Bloom, Crane’s best critic.

Harold Hart Crane was born in 1899 and took his own life, 32 years later, by throwing himself into the Atlantic ocean. We will never know the magnitude of the loss we suffered by his early death, but he is invoked in the same breath as Keats and Isaak Babel as great literary what-ifs. For my part, I have known of Crane since I was a teenager: he was the earliest love of the literary critic Harold Bloom, who was just two years old when Crane killed himself. Bloom discovered Crane in a Brooklyn library when he was only ten years old, taking out the book so often that he had the entirety of his verse, some 200 pages in my edition, memorized by the time he was twenty years old. It was also Bloom, among a small handful of other prescient literary critics, who first championed Crane’s genius, and so it is fitting that my centennial edition begins with an introduction supplied by Bloom, Crane’s best critic.

Crane is a difficult poet. He makes great demands upon his readers’ patience, requiring us to tease out complex conceits and reach for a dictionary with humbling frequency. Bloom calls this an “impacted density,” but I prefer Crane’s own description of a “logic of metaphor.” Discerning a coherent meaning from a Crane poem requires connecting a string of often complex metaphors, finding commonalities and probing the meaning of individual words, something that, you might argue, is the everyday business of reading poetry, but that becomes especially conspicuous (and, I might add, frustrating) in Crane’s verse. But where meaning is elusive, lyricism is abundant. I share Bloom’s judgment, and that of Crane’s biographer, Paul Mariani, that his poetic promise, his innate gift for language, surpasses that of his contemporaries Eliot, Stevens and Frost; Bloom goes so far as to class him above Dickinson and Whitman, and, if you compare their achievements against his at a similar age, it becomes difficult to disagree.

I will consign myself to discussing “Legend,” which opens his White Buildings and is, in my judgment, among his best and most mature works, a poem of singular beauty. It displays equally his lyricism and his metaphoric genius and is coherent enough to admit of more confident interpretations than some of his other short works.

Legend

As silent as a mirror is believed

Realities plunge in silence by…

I am not ready for repentance;

Nor to match regrets. For the moth

Bends no more than the still

Imploring flame. And tremorous

In the white falling flakes

Kisses are, –

The only worth all granting.

It is to be learned –

This cleaving and this burning,

But only by the one who

Spends out himself again.

Twice and twice

(Again the smoking souvenir,

Bleeding eidolon!) and yet again.

Until the bright logic is won

Unwhispering as a mirror

Is believed.

Then, drop by caustic drop, a perfect cry

Shall string some constant harmony, –

Relentless caper for all those who step

The legend of their youth into the noon.

Crane begins with a characteristically beautiful metaphor, teasing his reader with the ellipsis and hinting, perhaps, at one of the meanings of the title. A legend is both a notorious story or person, possibly mythical, and the explanatory wording attached to a map or diagram to explain the symbols used therein. It is this second meaning that the poem’s opening invokes, asking us to pay attention to those realities that might otherwise “plunge in silence by” – sound life advice, no doubt, but also guidance to his reader, similar to Shakespeare’s “Learn to read what silent love hath writ: / To hear with eyes belongs to love’s fine wit,” which alerts us to homonym usage.

The second stanza showcases some of Crane’s characteristic density and introduces the first-person speaker, who, though unwilling or unprepared, is made to feel guilty of something – his homosexuality? his refusal to be the son that either of his parents wanted him to be? his poetic vocation? take your pick, or, as the ambiguity allows, insert your own repentance-worthy misdeeds. And then this beautiful metaphor of the moth and the flame. If Crane’s sin is his poetic calling, which I think is certainly a good guess, then this refusal to repent calls to my mind Alexander Pope’s beautiful rhetorical question: “Why did I write? what sin to me unknown / Dipt me in Ink, my Parents’ or my own?” (from his “Epistle to Dr. Arbuthnot”). Crane, like Pope, was drawn to his trade, and will not apologize for it. Notice, also, the double meaning of “still,” used exactly as Keats uses it in his “Ode on a Grecian Urn.” The flame is both “still” in the sense that it is unbending, unmoving, and “still imploring,” a constant, unremitting call to Crane’s moth to self-immolate. And if the deed for which Crane’s narrator owes repentance is a romantic one (implicit in his being able to “match” regrets is someone with whom he can match them), kisses are venerated as “the only worth all granting,” but they come only amongst the “white falling flakes,” the charred remains of Crane’s moth.

The third stanza continues this metaphorical logic — the “cleaving” and the “burning” are to be learned (are they worth learning?) but only by the one who “spends out himself again,” who sacrifices himself to the flames. If it is love or if it is poetry – and the two, for Crane, are often interchangeable or indistinguishable – then it is bestowed only on those willing to undergo the cleaving and the burning, the destruction (sacrifice is a better word) of self. The fourth stanza enforces the need for this continued sacrifice (“Twice and twice … and yet again”), offering for reward “bright logic” that will go on, in the fifth stanza, to produce, drop by drop, “a perfect cry” stringing a “constant harmony” — again, is this cry poetic, the output that follows this opening poem, or is it romantic? Crane is intentionally ambiguous.

The final lines suggest that this self-immolation, this “relentless caper,” is a kind of rite of passage, a necessary advance for “all those who step / The legend of their youth into the noon.” What does it mean to step the legend of your youth into the noon? Dickinson, who is among the small handful of poets most important to Crane (others include Blake, Whitman, Wallace Stevens and Crane’s anti-hero Eliot, all of whom are referenced extensively in Crane’s works), called noon “the hinge of the day,” and no doubt it represents a pivotal moment, the fruition of your youthful “legend” (your personal narrative?) and the fulfillment of the promises that entails. Crane is a cult-like figure among poetry lovers precisely because his life, both as he lived it and as he would have others believe he lived it, represents a very real self-sacrifice in the service of art and ambition.

On a personal note: I mark every book I own with my name and the date I begin reading it. Crane’s collected poems have been on my bedside for exactly a year, companionate to my sleepless nights and restless mornings, and I have managed to write an entire blog post on him without discussing either “The Broken Tower” or his epic poem The Bridge. His difficulties have contributed, somewhat, to his relative obscurity (you will not find any modest reader of poetry with a Crane collection in hand, as you might with Keats or Eliot) but I urge you not to be dissuaded by his reputation; he rewards your efforts immensely.