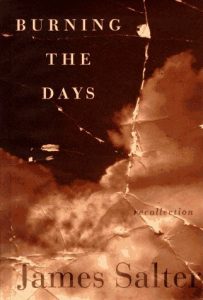

Not for the first time, I have read the memoirs of a novelist whose fiction is unknown to me, though in the case of James Salter this is perhaps excusable, as he would himself concede that his books are more often admired than read. Burning The Days, his first memoir, was published in 1997, more than 50 years after his birth, commemorating an extraordinary life: he was a fighter pilot in the Korean War, a Hollywood screenwriter, and a respected author; his social circle, from these various adventures, included Buzz Aldrin, Robert Redford, Vanessa Redgrave, Roman Polanski, Irwin Shaw, Truman Capote and Robert Mitchum. In other words, he did not lack for compelling anecdotes or intrinsically interesting experiences, the raw materials of any biography.

Not for the first time, I have read the memoirs of a novelist whose fiction is unknown to me, though in the case of James Salter this is perhaps excusable, as he would himself concede that his books are more often admired than read. Burning The Days, his first memoir, was published in 1997, more than 50 years after his birth, commemorating an extraordinary life: he was a fighter pilot in the Korean War, a Hollywood screenwriter, and a respected author; his social circle, from these various adventures, included Buzz Aldrin, Robert Redford, Vanessa Redgrave, Roman Polanski, Irwin Shaw, Truman Capote and Robert Mitchum. In other words, he did not lack for compelling anecdotes or intrinsically interesting experiences, the raw materials of any biography.

James Salter was born James Horowitz in New York in 1925, in the same hospital in which William Carlos Williams worked his day job (though the great poet did not, to Salter’s dismay, preside over his birth). He says very little of his childhood, except to remark that he was sheltered, and wished not to be: “In the street I ran from gangs of toughs. Tunney, Dempsey’s most famous opponent, soaked his fists every day in brine to make them invulnerable, my father had told me, to toughen them, and it was in some sort of brine that I hoped to steep myself.” Perhaps that is part of the reason why, when he was “seventeen, vain, and spoiled by poems,” he chose to decline his acceptance to Stanford in favor of attending his father’s alma mater, the much more rigid West Point. His description of the school merits quoting:

It was a place of bleak emotions, a great orphanage, chill in its appearance, rigid in its demands. There was occasional kindness but little love. The teachers did not love their pupils or the coach the mud-flecked fullback – the word was never spoken, although I often heard its opposite. In its place was comradeship and a standard that seemed as high as anyone could know. It included self-reliance and death if need be. West Point did not make character, it extolled it. It taught one to believe in difficulty, the hard way, and to sleep, as it were, on bare ground. Duty, honor, country. The great virtues were cut into stone above the archways and inscribed in the gold of class rings, not the classic virtues, not virtues at all, in fact, but commands. In life you might know defeat and see things you revered fall into darkness and disgrace, but never these.

Because he enters West Point in 1942, in the middle of the war, there is some rush to make the boys combat-ready, and in Salter’s case this involves flight lessons. After only a handful of flights assisted by an instructor, Salter is given sole command of an airplane for the first time, and his description of his first solo flight augurs a lifelong passion:

I felt at that moment – I will remember always – the thrill of the inachievable. Reciting to myself, exuberant, immortal, I felt the plane leave the ground and cross the hayfields and farms, making a noise like a tremendous, bumbling fly. I was far out, beyond the reef, nervous but unfrightened, knowing nothing, certain of all, cloth helmet, childish face, sleeve wind-maddened as I held an ecstatic arm out in the slipstream, the exaltation, the godliness, at last!

Nothing else in his life – not marriage, not sex, and certainly not writing – will inspire him to such exuberance. When one of his classmates whom he hardly knew, an ace fighter pilot, is killed “on the Continent,” Salter devotes more lines to his memory than to the death of his own father, not because he knew him, or cared for him, but because “he represented the flawless and was the first of that category to disappear.” The pursuit of perfection, it seems, preoccupies writers and combat aces alike.

The end of World War II is followed by a lengthy tour in the Air Force, culminating in his service in the Korean War. It was these events that inspired his first novel, The Hunters, which enjoyed greater commercial success as a Hollywood film starring Robert Mitchum than as a novel, but nonetheless served to launch him on a new journey in life, from fighter to writer of novels and screenplays. Salter describes handing in his Air Force resignation letter as one of the most painful things he has ever done, but he does not seem to relinquish his hold on flying until January of 1967, when, turning on the television, he learns of the death of Ed White and Gus Grissom, former friends and flight mates of his, in a disastrous Apollo 1 rehearsal test. The Wikipedia image of these men – strong-jawed, confident, on the cusp of mankind’s greatest adventure – gives us some glimpse into what Salter must have looked like, must have aspired to, at that time, and it’s no coincidence that the death of these young men (“The capsule had become a reliquary. They had inhaled fire, their lungs turned to ash”) is described within pages of the tragic death of his own daughter. “I have never been able to write the story,” he tells us. “I reach a certain point and cannot go on. The death of kings can be recited, but not of one’s child.” We learn of the existence of his daughter in the same paragraph that he informs us of her death, and other personal details – his failed first marriage, the death of his parents – are similarly elided.

He describes himself as entering a kind of depression after the death of his astronaut friends – though of his reaction to the death of his daughter, we learn nothing – that abates only with time, and leads him to a kind of conclusion: “The road was leading elsewhere, to what seemed a counterlife, if not in importance then in its distance from the commonplace – a life of freedom, style, and art, or the semblance of art.” The creative life, the life of the imagination, is indeed a counterlife, where the good do not have to die young, where parents do not have to bury their children, where perfection might exist as more than an ideal. Salter’s memoir testifies to this counterlife, its strengths and its limitations, and to a life well-lived, a life of travel and adventure and sun-kissing flight.