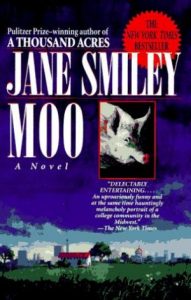

My introduction to Jane Smiley came in high school, when we were assigned her One Thousand Acres, a Pulitzer Prize-winning adaptation of King Lear set on an Iowa farm, together with Shakespeare’s tragedy. Smiley’s novel kicked my teeth in, as few novels have since, and until recently I thought of her exclusively as a writer of high tragedy. Moo, as the name and cover image suggest, is a comedy, a satire set on an unnamed Midwestern university specializing in agriculture and affectionately dubbed “Moo U.” Smiley spent years in Iowa, first as a student at the University of Iowa and then as a professor at Iowa State University, so one assumes she knows what of she speaks.

My introduction to Jane Smiley came in high school, when we were assigned her One Thousand Acres, a Pulitzer Prize-winning adaptation of King Lear set on an Iowa farm, together with Shakespeare’s tragedy. Smiley’s novel kicked my teeth in, as few novels have since, and until recently I thought of her exclusively as a writer of high tragedy. Moo, as the name and cover image suggest, is a comedy, a satire set on an unnamed Midwestern university specializing in agriculture and affectionately dubbed “Moo U.” Smiley spent years in Iowa, first as a student at the University of Iowa and then as a professor at Iowa State University, so one assumes she knows what of she speaks.

The novel begins by introducing us to Earl Butz, an enormous pig subject to an experiment by one of the university’s many eccentrics, Dr. Bo Jones (Smiley has a talent for names), who is determined to learn everything possible about pigs (“When I die, they’re going to say that Dr. Bo Jones found out something about hog”), beginning with how large they can grow given an unlimited supply of food. And so Earl’s business is “eating, only eating, and forever eating.” He is fed no less than five times a day by his hired helper and Moo U. student Bob Carlson, who develops a special affection for Earl. Earl is housed in Old Meats, a building that once served as a slaughterhouse and has now been all but abandoned, even though it stands in the exact centre of the campus. Around Old Meats, “militant horticulturalists,” led by the ’60s radical-turned-professor Chairman X, plant flowers after midnight, in violation of school policy.

Chapter after chapter, Smiley extends her cast of characters; there are students and professors, administrators and their secretaries – even Earl Butz is given a voice. Orville T. Early, the state governor, believes that there is a plot within the university to undermine American society:

It was well known among the legislators that the faculty as a whole was determined to undermine the moral and commercial well-being of the state, and that supporting a large and nationally famous university with state money was exactly analogous to raising a nest of vipers in your own bed.

Dr. Lionel Gift, the university’s best-paid professor, has absolute faith in the market, to the extent that he refers to his students as “customers” and, unlike his peers, applauds the impending budget concession that will triple all class sizes because it will mean a threefold increase in his productivity. His introduction, in a chapter titled “Homo Economicus,” demands to be quoted, if only to sample Smiley’s pitch-perfect satire:

Dr. Lionel Gift, distinguished professor of economics, was, as everyone including Dr. Gift himself agreed, a deeply principled man. His first principle was that all men, not excluding himself, had an insatiable desire for consumer goods, and that it was no coincidence that what all men had an insatiable desire for was known as “goods,” for goods were good, which is why all men had an insatiable desire for them. In this desire, all men copied the example of their Maker, Who was so Prodigious and Prodigal in His production of goods that His inner purpose could only be the limitless desire to own the billions and billions of light-years, galaxies, solar systems, worlds, life-forms, molecules, atoms, and subatomic particles that He had produced. Perfect in the balance He incarnated of production and consumption, He represented a model that the human race not only COULD strive for, but MUST strive for. In this, his private theology, Dr. Gift felt that he had reconciled faith and relativity, self and the vastness of time and space. In fact, every time astronomers demonstrated that there was more out there, and that it was farther away than anyone had thought, every time a physicist successfully quantified vastness, or even minuteness, for that matter, Dr. Gift felt a genuine thrill, the thrill of toiling toward the holy.

Smiley pits Chairman X, the radical horticulturalist, on a collision course with Gift when the economist, eyes keenly fixed on profit margins, writes a paper endorsing a proposal to mine gold from one of the world’s last virgin cloud forests in Costa Rica – and without disclosing that the owner of the recommended mining company is a university benefactor.

The university’s funding and the ecological future of Costa Rica are not the novel’s only stakes; Smiley is also concerned with her characters’ personal lives. An all-female dorm figures prominently, and the sex lives of the professors are mined for comedy (one chapter is titled “Who’s in bed with whom”). The power struggle between university administrators and professors, and the key role played by the sassy secretaries, figures prominently. Here is Smiley’s easy-to-miss deadpan humor on display in an exchange between Mrs. Loraine Walker, the secretary for the provost, and the university’s associate vice-president:

“Associate Vice-President Brown”

“Marvelous day for this time of year, don’t you think?”

“The end of September frequently offers superior weather in this climate, Sir.”

“Oh, goodness, no need for that. You know, minimizing the expressions of hierarchy within the organization seems actually to mitigate its negative effects and to draw all the employees at every level into a more profound dialogue with one another. Some of the best ideas come from staff and even blue-collar employees.”

“May I help you with, Associate Vice-President Brown?”

It’s difficult to say whether Associate Vice-President Brown is aware of the irony in his objecting to being called “Sir” but not his title, or if he is being intentionally condescending or simply tone deaf in his final statement about “staff and even blue-collar employees,” but either way he is no match for Loraine Walker in a battle of wits. In another exchange, with Dr. Gift, Loraine quotes Wordsworth’s famous sonnet “The World Is Too Much With Us,” but the literal-minded Dr. Gift can only nod in approval at the prospect of “getting and spending.”

Moo is an extremely funny novel, and a brilliant but loving send-up of the modern university, and it says something flattering about Smiley that she can so easily transition from tragedy to comedy, from pathos to satire.