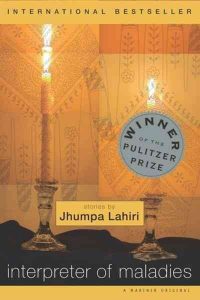

I found Jhumpa Lahiri’s debut collection of short stories, Interpreter Of Maladies, tucked between young adult books at a local used book sale. I did not know it had won the Pulitzer Prize until I saw the badging on the front cover. Apart from this evidence of its being well received, I knew nothing about the book or its author, apart from the occasional mention of her name from friends or on literary blogs. Lahiri was born in London, the daughter of Bengali Indian immigrants, but her family left for America when she was still very young, following her father’s appointment to librarian at the University Of Rhode Island. The short stories in this collection draw heavily from these locales – India, London, the United States and the university – and on the challenges and, at times, rewards, of existing between worlds.

I found Jhumpa Lahiri’s debut collection of short stories, Interpreter Of Maladies, tucked between young adult books at a local used book sale. I did not know it had won the Pulitzer Prize until I saw the badging on the front cover. Apart from this evidence of its being well received, I knew nothing about the book or its author, apart from the occasional mention of her name from friends or on literary blogs. Lahiri was born in London, the daughter of Bengali Indian immigrants, but her family left for America when she was still very young, following her father’s appointment to librarian at the University Of Rhode Island. The short stories in this collection draw heavily from these locales – India, London, the United States and the university – and on the challenges and, at times, rewards, of existing between worlds.

Thus we encounter, for example, Mrs. Sen, the wife of a mathematics professor who is struggling to adjust to her new life in America. She lives in the suburbs but cannot drive – surely a form of imprisonment – and with her husband at work all day long, and her friends and family all in India, loneliness and a terrible sense of isolation quickly pervade her life. This would be a sufficiently rich plot for most writers, but Lahiri is forever manipulating point of view, and so she has Mrs. Sen take on a babysitting role for a young American boy, Eliot, whose single mother – predisposed to distrust anyone responsible for her child’s wellbeing – is uneasy with the arrangement. Gradually, Eliot becomes accustomed to the oddities of Mrs. Sen’s life: her ornate manner of dress, and the multicoloured saris she dons; her meticulous preparation of every meal, with hours spent chopping vegetables each day; and above all, her obsession with finding the freshest possible fish, a staple of her life in India. Through his perspective, we come to appreciate the loneliness of her predicament, and the cultural differences that separate two continents. Consider this exchange of dialogue:

“Eliot, if I began to scream right now at the top of my lungs, would someone come?

“Mrs. Sen, what’s wrong?”

“Nothing. I am only asking if someone would come.”

Eliot shrugged. “Maybe.”

“At home, that is all you have to do. Not everybody has a telephone. But just raise your voice a bit, or express grief or joy of any kind, and one whole neighborhood and half of another has come to share the news, to help with arrangements.”

In another memorable scene, Mrs. Sen plays a cassette tape for Eliot containing recorded messages from friends and family, a departing gift before her journey to America. On the second day that she plays the tape, she pauses it at the sound of her grandfather’s voice, before informing Eliot that she has just received word that he has died.

In another, exquisitely sympathetic story, an Indian man journeys from Calcutta to London to Cambridge, Massachusetts, where he can only afford to rent a room from a centenarian widower, Mrs. Croft, a strict old woman who long ago crippled her hands by playing the piano too often. The reader might be forgiven for suspecting that, with a cultural and generational divide between them, their relationship would be marred by misunderstanding or suspicion, but on the contrary: Mrs. Croft is charmed by her tenant’s unfailing manners and quiet devotion to her, and the young man, in his turn, develops an affection for his host. Their relationship must end when the young man’s bride, via an arranged marriage, finally secures a visa and arrives in Cambridge, necessitating a move to a larger apartment. The wife, barely off the plane, has had no time to adopt herself to American customs, and when she arrives to meet her husband’s former landlord, she wears a full sari and an ankle-length skirt, with a bindi (that famous “dot” of makeup) on her forehead. There is a brief moment of tension, yet another opportunity for the cultural collision to turn ugly, but then Mrs. Croft pronounces her judgment: “She is a perfect lady.”

These stories deal with great divides and jarring experiences – including the arranging and breaking up of marriages, infidelity, and a stillborn birth – but they resist the impulse to take sides, to point an accusatory finger; at every opportunity, Lahiri opts for empathy, and she teaches her reader to do the same.