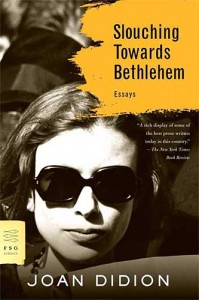

Joan Didion will turn 80 later this year, a milestone that will mark nearly a half-century of journalism and cultural commentary that place her among the very best nonfiction writers of the 20th century. But longevity has its downsides. She buried her husband of nearly 40 years in 2003, and her only daughter died two short years later. It’s difficult for me now to look upon the cover of my edition of Slouching Towards Bethlehem, her first collection of essays published when she was in her early thirties, and reconcile the sunglass-wearing face that stares back at me and the life these essays reveal, if only obliquely, with my image of her in the present. The gap is that of a lifetime, and yet these essays remain remarkably vivid, a testament to a time (the ’60s) and a place (California) and a mind that sought to make sense of the chaos.

Joan Didion will turn 80 later this year, a milestone that will mark nearly a half-century of journalism and cultural commentary that place her among the very best nonfiction writers of the 20th century. But longevity has its downsides. She buried her husband of nearly 40 years in 2003, and her only daughter died two short years later. It’s difficult for me now to look upon the cover of my edition of Slouching Towards Bethlehem, her first collection of essays published when she was in her early thirties, and reconcile the sunglass-wearing face that stares back at me and the life these essays reveal, if only obliquely, with my image of her in the present. The gap is that of a lifetime, and yet these essays remain remarkably vivid, a testament to a time (the ’60s) and a place (California) and a mind that sought to make sense of the chaos.

I am only now beginning to grasp how momentous the decade of the 1960s was, how unprecedented and far-reaching were the social changes taking place, or how ominous the national mood could be. The collection’s title, taken from Yeats’ “The Second Coming,” speaks to a sense of loss, or at the very least a loss of direction. The American identity itself was being challenged, and few offered any concrete sense of what would take its place. Thus Didion writes:

It was not a country in open revolution. It was not a country under enemy siege. It was the United States of America in the cold late spring of 1967, and the market was steady and the G.N.P. high and a great many articulate people seemed to have a sense of high social purpose and it might have been a spring of brave hopes and national promise, but it was not, and more and more people had the uneasy apprehension that it was not.

This particular essay has Didion interviewing a generation of youths, teenagers to twenty-somethings, who have forsaken the life their parents led in favor of, well, what, exactly? Drugs, and music, and a good deal of pre-marital sex, sans emotional hang-ups (“I’ve had this old lady for a couple of months now, maybe she makes something special for my dinner and I come in three days late and tell her I’ve been balling some other chick, well, maybe she shouts a little but then I say ‘That’s me, baby,’ and she laughs and says ‘That’s you.'”). This is life free of what Didion calls “the old middle-class Freudian hang-ups,” but the question left unanswered, the question Didion is asking implicitly with every sardonic anecdote, is one of purpose. What is the alternative to those Freudian hang-ups, and is it really the better choice, or is it merely the more pleasurable one?

Her diagnosis of the counterculture (“the desperate attempt of a handful of pathetically equipped children to create a community in a social vacuum”) has the force of judgment without its condemnation. She has compassion for this “army of children,” and locates the root of their malaise in the preceding generation:

At some point between 1945 and 1967, we had somehow neglected to tell these children the rules of the game we happened to be playing. Maybe we had stopped believing in the rules ourselves, maybe we were having a failure of nerve about the game. Maybe there were just too few people around to do the telling.

Faith in religion and government fell precipitously, the pill separated sex from its consequences, and the threat of nuclear annihilation made hedonism not just appealing but rational. But the world didn’t end, as hedonism always must, and the dilemmas of meaning and direction persist.

She follows up “Slouching Towards Bethlehem” with essays “On Keeping A Notebook” and “On Self-Respect,” and it’s particularly jarring to read these in this order. How does hedonism do battle with self-respect, which Didion defines as “a discipline, a habit of mind that can never be faked but can be developed, trained, coaxed forth”? Here is Didion again, this time from the essay “Why I Write,” not included in this selection:

In many ways writing is the act of saying I, of imposing oneself upon other people, of saying listen to me, see it my way, change your mind. It’s an aggressive, even a hostile act. You can disguise its qualifiers and tentative subjunctives, with ellipses and evasions —with the whole manner of intimating rather than claiming, of alluding rather than stating—but there’s no getting around the fact that setting words on paper is the tactic of a secret bully, an invasion, an imposition of the writer’s sensibility on the reader’s most private space.

In my humble opinion, this is among the truest things ever said about writing, and I can’t help but feel, in these essays and in their arrangement, that Didion is fulfilling the role of secret bully, imposing her thoughts and opinions on me, however surreptitiously. This all writers do. Good writers manage to make those thoughts and opinions meaningful, even vitally important, and great writers find some harmony between what they’re saying and how they say it. Joan Didion is a great writer.