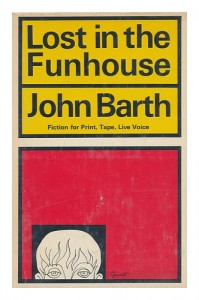

John Barth, like Donald Barthelme, is another writer whose influence has managed to outstrip his fame. Rightly acknowledged as a master of postmodernist fiction, he remains little read by the general public, probably because of his formal difficulty. And yet Lost In The Funhouse is a lively collection, at times difficult, certainly, but also wildly playful, humorous and inventive. There is a richness to his prose, a quality of delight and exuberance, that belies the cynicism inherent in so many of his stories and is part of the great joy of reading him. Barth’s work is also predominantly metafictional, which is to say that he employs stylistic elements to draw attention to the artifice of the work. And though he did not invent the technique, his influential essay “The Literature of Exhaustion,” which speaks of the near-futility of continuing in the realist mode, launched a hundred imitators.

John Barth, like Donald Barthelme, is another writer whose influence has managed to outstrip his fame. Rightly acknowledged as a master of postmodernist fiction, he remains little read by the general public, probably because of his formal difficulty. And yet Lost In The Funhouse is a lively collection, at times difficult, certainly, but also wildly playful, humorous and inventive. There is a richness to his prose, a quality of delight and exuberance, that belies the cynicism inherent in so many of his stories and is part of the great joy of reading him. Barth’s work is also predominantly metafictional, which is to say that he employs stylistic elements to draw attention to the artifice of the work. And though he did not invent the technique, his influential essay “The Literature of Exhaustion,” which speaks of the near-futility of continuing in the realist mode, launched a hundred imitators.

The opening “story” of Lost In The Fun House, “Frame-Tale,” is less a narrative than a one-page manual instructing the reader to cut a vertical strip down the page, with “Once Upon A Time There” on one side and “Was A Story That Began” on the other; if followed, the end product is a Möbius strip, a non-orientable band with no discernible beginning or end – a fitting metaphor for some of Barth’s stranger stories, which include “Petition,” a story about two Siamese twins (where does one begin and the other end?) or the infamous “Night-Sea Journey” following a spermatozoon on its journey to fertilize an egg. Perhaps my favorite of the collection, however, were the triad of stories – “Echo,” “Menelaiad” and “Anonymiad” – that reconfigure Greek mythology to highlight not only the more human but the more domestic qualities of their mythological characters. Thus “Echo” envisions the difficulties that Narcissus, the hunter boy of incredible beauty, has in loving anything or anyone other than himself, with Barth cleverly confronting him with the Nymph echo, who, nothing herself, merely repeats what others say. Narcissus falls in love with Echo, though only because she is a shadow of him – as apt a parable for dysfunctional relationships as ever was conceived, calling to mind some words of Robert Frost in “The Most Of It,”

He would cry out on life, that what it wants

Is not its own love back in copy speech,

But counter-love, original response.

Barth has great fun mimicking the idioms of ancient Greece, or at least Homeric Greece, sprinkling his text with references to “dawn’s rosy fingers” and other iconic images from the epics, but these are thoroughly modern re-imaginings and there is a kind of giddy thrill in watching the heroes of the Iliad and the Odyssey obsessing over the fidelity of their wives, or picturing the beauteous Helen as a coquettish young wife destined to inadvertently cause a war.

I cannot say whether the formal playfulness adds to Barth’s vision, nor do I like to concede that irony has supplanted sincerity in fiction, but Barth justifies his inventiveness with an equal mix of humor, insight and verbal dexterity that makes this collection memorable and influential.