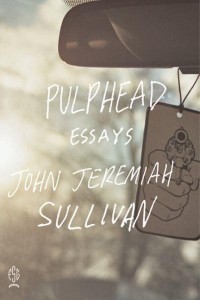

In his letter of resignation from Esquire magazine, Norman Mailer wrote, “Good-by now, rum friends, and best wishes. You got a good mag (like the pulp-heads say).” To the best of my knowledge, John Jeremiah Sullivan has never worked for Esquire, but he has contributed non-fiction pieces to GQ – not to mention Harper’s, the New York Times Magazine and The Paris Review, where he is the “southern editor.” Pulphead, whose title is taken from the aforementioned Mailer quotation, is a collection of these writings, somewhat polished for the larger book format, and it has been gathering plaudits ever since its release in 2011.

In his letter of resignation from Esquire magazine, Norman Mailer wrote, “Good-by now, rum friends, and best wishes. You got a good mag (like the pulp-heads say).” To the best of my knowledge, John Jeremiah Sullivan has never worked for Esquire, but he has contributed non-fiction pieces to GQ – not to mention Harper’s, the New York Times Magazine and The Paris Review, where he is the “southern editor.” Pulphead, whose title is taken from the aforementioned Mailer quotation, is a collection of these writings, somewhat polished for the larger book format, and it has been gathering plaudits ever since its release in 2011.

Most of these essays are deserving of their “pulp” categorization, at least with regards to their subject matter: Sullivan writes on musicians (Michael Jackson, Axl Rose, Bunny Wailer, as well as Christian rock and forgotten jazz artists), MTV’s The Real World and the experience of having a popular teen television drama (The CW’s One Tree Hill) filmed in his home. These are juxtaposed with more weighty pieces on, for example, American pre-modern cave art, the Tea Party, his experiences as a writer-in-residence/live-in caretaker for Andrew Nelson Lyttle, of the Southern Agrarian literary movement, or his brother’s near fatal encounter with a poorly wired microphone. These essays are by turns insightful, amusing and provocative, and gradually give us a portrait of our writer: he’s a Southerner (“My people were those strange Southerners you don’t often read about in histories of the Civil War: white landowners who owned slaves but fought for the North on Republican principles”) and an ex born-again Christian; he has watched more reality television than any self-respecting writer is likely to admit, and smokes pot often enough that it’s mentioned in several of the pieces. Using a combination of self-deprecating humor and confessional asides (“Remember your senior year in college, what that was like? Partying was the only thing you had to worry about, and when you went out, you could feel people thinking you were cool. The whole idea of being a young American seemed fun. Remember that? Me neither.”), he earns his readers’ trust: this is someone like us, someone we can relate to. It’s an old trick, as far as essay writing goes, and it makes the inevitable insights and incongruent asides all the more striking. It was also one of the hallmarks of the late David Foster Wallace’s essay writing, and that is the writer whose influence most profoundly marks Sullivan’s writing.

This isn’t a particularly bold insight: Wallace’s two major nonfiction collections, Consider The Lobster and A Supposedly Fun Thing I’ll Never Do Again, revived the nonfiction essay, mostly by emphasizing the first-person experience and blurring the lines between storytelling and reporting. And this is what Sullivan, an avowed Wallace fan, is doing in nearly every piece. Thus, for example, the first essay about his trip to a Christian rock concert begins with straight reporting: I arrived here, saw this, did that, met so-and-so, before we’re taken into the author’s more personal struggles with belief, his confrontation with the born-again Christians who befriend and instruct him, and his more secular reading, culminating in this rather Nietzschean insight about Christ:

Forget the Epistles, forget all the bullying stuff that came later. Look at what He said. Read the Jefferson Bible. Or better yet, read The Logia of Yeshua, by Guy Davenport and Benjamin Urrutia, an unadorned translation of all the sayings ascribed to Jesus that modern scholars deem authentic. There’s your man. His breakthrough was the aestheticization of weakness. Not in what conquers, not in glory, but in what’s fragile and what suffers – there lies sanity. And salvation.

If the everyman persona isn’t fully punctured by the invocation of the Logia, subsequent essays – on the pre-modern cave paintings of Kentucky, for example, or on the eccentric naturalist Constantine Samuel Rafinesque – reveal our author to be more than a pot-smoking, reggae-loving ex-Christian. And that’s about the time when you start to meditate not only on what is being said within the essays, but what their very assemblage says about Sullivan’s intentions. Three essays, for example, deal with the blurred lines between the world as we know it and the world as portrayed in our popular entertainment. These are the essays on MTV’s The Real World, a reality television show; the essay on his brother’s near-fatal electrocution, which was – surprise, surprise – quickly transformed into a television show; and his experiences renting out his home for use on a teen melodrama. Contrast these with the distinctly backward-looking essays on Andrew Lyttle – 90-years-old when, or thereabouts, when Sullivan first meets him – and pre-modern cave paintings, or jazz music so old and rare that enthusiasts spend years hunting down recordings, and you get a funny patchwork of our particular moment, the postmodern, media-saturated world that David Foster Wallace wrote about with such acuity.

Sullivan takes us on a tour through our world, forcing us to take a second look at the familiar and the mundane, never judging or condemning but prodding us, gently, to see just how strange our moment really is.