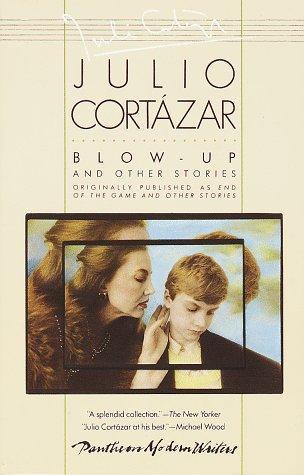

The Brussels-born Argentinian writer Julio Cortázar was one of the figureheads of the Latin American Boom, the literary movement that introduced Europe and eventually the English-speaking world to the remarkable talents of South America – Peru’s Mario Vargas Llosa, Colombia’s Gabriel Garcia Márquez, and Mexico’s Carlos Fuentes – and occasioned a reappraisal of older South American writers too long neglected by the Global North, most notably Jorge Luis Borges, Juan Rulfo and Ernesto Sabato. There’s some small irony in the role Cortázar played as figurehead of a continent he seldom visited: most of his life was spent in France, between Paris and his farm in Southern France, home to his legendary library spanning thousands of volumes across 26 different languages. His fame in the English-speaking world rests on this collection of short stories, culled from three of his first three works of short fiction, translated by Paul Blackburn and originally published as End of the Game and Other Stories in 1968, as well as the 1966 Michelangelo Antonioni film Blowup starring Vanessa Redgrave, based upon this collection’s titular story. So, what of the stories that helped kick up such a fuss?

From the opening story, the reader quickly apprehends that reality’s ordinary rules are, in Cortázar’s world, sharply bent. The supernatural, the improbable, and the extraordinary feature prominently in the plots. In the first story, “Axolotl,” a man gradually finds himself identifying more and more with an axolotl, a Mexican walking fish, until one day his consciousness enters into the fish itself:

Only one thing was strange: to go on thinking as usual, to know. To realize that was, for the first moment, like the horror of a man buried alive awaking to his fate. Outside, my face came close to the glass again, I saw my mouth, the lips compressed with the effort of understanding the axolotls. I was an axolotl and now I knew instantly that no understanding was possible. He was outside the aquarium, his thinking was a thinking outside the tank. Recognizing him, being him himself, I was an axolotl and in my world. The horror began – I learned in the same moment – of believing myself prisoner in the body of an axolotl, metamorphosed into him with my human mind intact, buried alive in an axolotl, condemned to move lucidly among unconscious creatures. But that stopped when a foot just grazed my face, when I moved just a little to one side and saw an axolotl next to me who was looking at me, and understood that he knew also, no communication possible, but very clearly. Or I was also in him, or all of us were thinking humanlike, incapable of expression, limited to the golden splendor of our eyes looking at the face of the man pressed against the aquarium.

There’s narrative innovation here, to be sure, a subtle twist on the buried-alive trope of horror fiction, but what unsettles us isn’t the brute fact of the transformation but how Cortázar conveys it in language: “I was an axolotl and now I knew instantly that no understanding was possible.” Language used to signal a failure of language, a barrier of communication as insuperable as the glass wall of the tank separating man from fish. That theme, of language’s inadequacy, reaches its apotheosis in “Blow-Up,” which begins with an admission of failure:

It’ll never be known how this has to be told, in the first person or in the second, using the third person plural or continually inventing modes that will serve for nothing. If one might say: I will see the moon rose, or: we hurt me at the back of my eyes, and especially: you the blond woman was the clouds that race before my your his our yours their faces. What the hell.

Confused, yet? That’s because our narrator, Roberto Michel, a French-Chilean translator and amateur photographer, is confused, and Cortázar wants us to share in his discomfort and uncertainty.

It’s going to be to difficult because nobody really knows who it is telling it, if I am or what actually occurred or what I’m seeing (clouds, and once in a while a pigeon) or if, simply, I’m telling a truth which is only my truth, and then is the truth only for my stomach, for this impulse to go running out and to finish up in some manner with, this, whatever it is.

Adding to our confusion, Cortázar will slip between first- and third-person narration, thus in the middle of a lengthy “I” sentence we will get an aside “(but Michel rambles on to himself easily enough, there’s no need to let him harangue on this way).” When Michel takes his camera to the park, to take advantage of the day’s excellent light, he eventually comes across a scene unfolding between a young boy and what, at first, he takes to be his lover, and then, upon further consideration, his mother. There is an age gap between them, but their posture resembles that of “couples when we see them leaning up against the parapets or embracing on the benches in the squares.” Upon further inspection, Michel also notices something else: the young boy is nervous.

As I had nothing else to do, I had more than enough time to wonder why the boy was so nervous, like a young colt or a hare, sticking his hands into his pockets, taking them out immediately, one after the other, running his fingers through his hair, changing his stance, and especially why he was afraid, well, you could guess that from every gesture, a fear suffocated by his shyness, an impulse to step backwards which he telegraphed, his body standing as if it were on the edge of flight, holding itself back in a final, pitiful decorum.

He decides to stay and watch the pair, intrigued by his confusion over what he sees, aware that his vision is fallible: “I think that I know how to look, if it’s something I know, and also that every looking oozes with mendacity, because it’s that which expels us furthest outside ourselves […].” While he watches, he projects all kinds of possible scenarios onto them, that might help explain why they’re together in a park and why they’re behaving strangely, until he surreptitiously raises his camera, “sure that I would catch the revealing expression, one that would sum it all up.” The woman, however, notices, and approaches him to complain, while the young boy – startled by the knowledge that they have been watched – takes the opportunity to flee the scene. The real drama comes later, when Michel develops the film and “blows up” the image via projector, to study it in greater detail, only to realize that the innocent scene he had stumbled on and inadvertently interrupted by his taking of the photo was in fact an attempted homosexual seduction of a young boy by an adult man. The realization of the true nature of the scene, as well as the inadequacy of his own sight, causes Michel to have a psychotic breakdown, which Cortázar renders in chilling detail: the stationary picture begins to move, as if the scene is repeating itself:

Everything was going to resolve itself right there, at that moment; there was like an immense silence which had nothing to do with physical silence. It was stretching out, setting itself up. I think I screamed, I screamed terribly, and that at that exact second I realized that I was beginning to move toward them, four inches, a step, another step […]

The story’s original title was “Las babas del diablo,” the devil’s drool, derived from an expression about proximity to evil: you’re so close to it that “you can feel the devil’s drool.”

In these stories, Cortázar reveals the full power of language not only to reveal and to build, but to conceal, mislead, and deconstruct. In every story, we readers are being manipulated, toyed with, led astray, and the experience of being so completely at the mercy of a storyteller determined to unsettle us or unseat our lazy assumptions about narrative and certainty is horrifying, in the truest sense of that word.