In Kafka’s famous letter to his father, published after Kafka’s death and against his wishes, one line in particular perfectly encapsulates the essential qualities of an abusive father-son relationship: “For me you took on the enigmatic quality that all tyrants have whose rights are based on their person and not on reason.” He means that his father’s displeasure with him was capricious, unrelated to any wrongdoing on his part but liable to erupt at any moment. For a young child, this capriciousness ruptures the chain of cause and effect, essential to orienting oneself in the world, and for the young Kafka it meant the fatal internalization of guilt. If it is not my actions that are bad, it is my person, my very being, that is corrupt. So completely has Kafka explored the conscience of the constitutionally guilty person that it has become impossible to approach the subject matter without invoking his spirit, but the third book in Karl Ove Knausgaard’s searingly personal memoir, My Struggle, manages to find new ways to explore old themes.

In Kafka’s famous letter to his father, published after Kafka’s death and against his wishes, one line in particular perfectly encapsulates the essential qualities of an abusive father-son relationship: “For me you took on the enigmatic quality that all tyrants have whose rights are based on their person and not on reason.” He means that his father’s displeasure with him was capricious, unrelated to any wrongdoing on his part but liable to erupt at any moment. For a young child, this capriciousness ruptures the chain of cause and effect, essential to orienting oneself in the world, and for the young Kafka it meant the fatal internalization of guilt. If it is not my actions that are bad, it is my person, my very being, that is corrupt. So completely has Kafka explored the conscience of the constitutionally guilty person that it has become impossible to approach the subject matter without invoking his spirit, but the third book in Karl Ove Knausgaard’s searingly personal memoir, My Struggle, manages to find new ways to explore old themes.

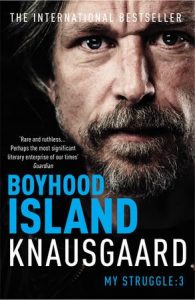

We begin with his childhood in Tromøya, an island in southern Norway, where the young Karl Ove, four years younger than his elder brother, has a kind of Edenic playground at his disposal. The housing estate on which his family lives has only newly been constructed, and much of the island remains undeveloped, encompassing pristine woodlands and tall hills, as well as the ocean shores. The natural beauty and freedom of the outdoors become all the more appealing to him in contrast to his home life, which is terrorized by his father. Knausgaard Senior is a teacher in the local high school, a young father married to a young wife, and a petty tyrant, someone who takes out his hidden frustrations on his two young sons with dictatorial delight. The Knausgaard household is planted thick with rules – the lawn cannot be walked on, the television cannot be touched, reading books is an idler’s occupation – but it quickly becomes apparent that the rules exist only as a pretext for punishment, and can be invoked under the flimsiest of circumstances. In one memorable instance, Karl Ove is called into the kitchen and offered an apple by his father. He refuses, saying he has already eaten two, but his father insists, forcing him to eat apple after apple as punishment for eating without permission. In another episode, when only Karl Ove and his father are alone in the house, sitting down for breakfast, he pours himself a bowl of cereal and milk, only to discover that the milk has gone sour. Rather than express disgust and throw out the cereal – and thereby risk his father’s wrath – he opts instead to finish his breakfast, sour milk and all. For his mother, he has much fonder feelings: “if there was someone there, at the bottom of the well that was my childhood, it was her, my mother, mum.” Karl Ove’s mother is kind and caring, someone who goes out of her way to play with her children and to enquire about their lives, not out of suspicion but genuine curiosity; she is, in every way, the “counterbalance” to his father’s malevolence. “She saved me,” Karl Ove writes, “because if she hadn’t been there I would have grown up alone with dad, and sooner or later I would have taken my own life, one way or another.”

Boyhood Island covers the usual trials of childhood, from the struggle for peer acceptance to the creation of an identity, but it does so with unusual insight and sympathy. We see life not only through the eyes of a child, but of a young boy navigating the specific pressures and problems of his gender. And, though it is subtle, there is a wider social commentary at play here as well. Looking back on his childhood, Karl Ove makes much of the fact that his housing estate was one of many manifestations of a “planned society,” a product of a 1960s idealism that clashes so profoundly with the painful nature of his family life. What social planner could have envisioned or accounted for Knausgaard Senior?

I remain riveted by this project and Knausgaard’s unflinching honesty; in a very real sense, his unburdening through this memoir has been no less cathartic for his readers.