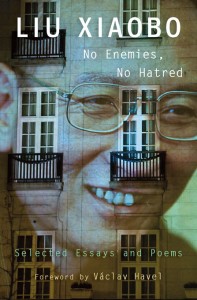

The 2010 Nobel Peace Price was awarded, in absentia, to Chinese writer and social critic Liu Xiaobo. He could not attend the award ceremony in Oslo, however, because he was serving his fourth prison term in China, this time for the crime of “inciting subversion of state power.” Ever on the alert for threats to their rule, the commissars of the People’s Republic took matters even further, first by placing Liu’s wife on house arrest and pressuring foreign diplomats not to attend the ceremony, then by censoring, as far as they were capable, any and all news of the event within China. Russia and Saudi Arabia – auspicious allies! – quickly joined the PRC in condemning this pernicious intervention in China’s domestic policy. So who is Liu Xiaobo and what dangerous, subversive opinions does he harbor that a solitary award could precipitate such an international kerfuffle?

The 2010 Nobel Peace Price was awarded, in absentia, to Chinese writer and social critic Liu Xiaobo. He could not attend the award ceremony in Oslo, however, because he was serving his fourth prison term in China, this time for the crime of “inciting subversion of state power.” Ever on the alert for threats to their rule, the commissars of the People’s Republic took matters even further, first by placing Liu’s wife on house arrest and pressuring foreign diplomats not to attend the ceremony, then by censoring, as far as they were capable, any and all news of the event within China. Russia and Saudi Arabia – auspicious allies! – quickly joined the PRC in condemning this pernicious intervention in China’s domestic policy. So who is Liu Xiaobo and what dangerous, subversive opinions does he harbor that a solitary award could precipitate such an international kerfuffle?

As it turns out, it does not take much provocation to become an enemy of the state in China: Liu Xiaobo is a kindly academic with a background in the study of literature, a humanist whose opinions incline towards democracy, freedom and individual liberty, and not a firebrand of revolution eagerly awaiting the violent overthrow of the ruling party. He has, in fact, repudiated the fast track to change, having been a student of history long enough to know that violent upheaval seldom gives way to stable, representative government. But China’s ruling elites are right to fear him all the same, for history furnishes many examples of changes wrought by men of quiet principle and unshakeable resolution. In his essay “To Change A Regime By Changing A Society,” cited as evidence against him at his trial, Liu presents a litany of charges against Chinese society post-Mao – from arbitrary dictatorial rule and economic dependence on the state to a “tyranny of the mind that arose from an ideology that claimed to explain everything and to possess all virtue” – before presenting hope that each of these small despotisms may be on the way out:

The steady growth of private capital has eaten away at the regime’s onetime economic monopoly; increasingly diverse concepts of value are challenging the monopoly on “thought”; the expanding rights-defense movement is eroding the power of government officials to act on caprice; and advances in public courage have made the specter of political terror ever less frightening.

The early essays of this volume flesh out this hopeful thesis, drawing on the influence of the Internet in China – the bane of authoritarians seeking to impose their will and control public opinion – and the steady growth of private property rights, particularly for farmers, many of whom witnessed the state appropriate land that had belonged to their parents and grandparents “for the greater good.”

But Liu endeared himself to me for being no less critical of his fellow citizens, whose complacency and moral cowardice have often made them tacitly responsible for the crimes of their government.

The post-Tiananmen generation, raised with prospects of moderately good living conditions inside a culture of pragmatism, is not very interested in things like deep thought, noble character, incorruptible and well-ordered government, humane values, or transcendent moral concerns. Their approach to life is practical and opportunistic.

His theory is that the Chinese people have been conditioned to accept a degraded life, an unfree existence, made tolerable only by their increasing material prosperity, and I confess that his criticisms of his fellow citizens seem to me frighteningly applicable in the West, as well. “With the devaluation of faith and the sacred, people are enthralled by carnal desires. Stripped of compassion and a sense of justice, they are reduced to callous, calculating economic beings, content with a life of ease.” But not all of them. The Internet has given Liu a larger audience, connecting him with likeminded people who disseminate his writings through vast underground networks, slowly but surely eroding the country’s faith in its self-appointed leaders. And his Nobel victory – the first of its kind for a Chinese citizen residing in China – has given him international support. His writings, at least in English, do not have the scripture-like authority of Dr. King’s, nor do they rival Orwell’s for insight and intuition, but they present us with a noble mind sincerely grappling with the problems of his society. And the PRC, in committing the moral calamity of incarcerating him, have validated his concerns. History, no doubt, will appreciate the irony.