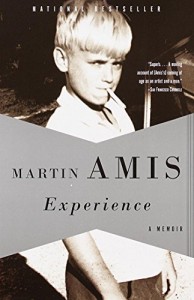

In 1994, Frederick and Rosemary West were charged with the abduction and murder of ten young women. The details of their horrific crimes are shocking, and continue to captivate Britain and the world, as the lurid and macabre are wont to do. Among the deceased was one Lucy Partington, a young woman studying English Literature at Exeter University at the time of her abduction, in January of 1974. Two decades would pass before her dismembered remains were recovered and her grieving family learned the secret of her disappearance. How does one come to terms with such horrors? Lucy Partington is Martin Amis’ cousin, one of his “missing,” and the question of how to overcome this kind of grief winds its away through his memoir Experience, taking on many forms – not just death, but divorce, separation, loss.

In 1994, Frederick and Rosemary West were charged with the abduction and murder of ten young women. The details of their horrific crimes are shocking, and continue to captivate Britain and the world, as the lurid and macabre are wont to do. Among the deceased was one Lucy Partington, a young woman studying English Literature at Exeter University at the time of her abduction, in January of 1974. Two decades would pass before her dismembered remains were recovered and her grieving family learned the secret of her disappearance. How does one come to terms with such horrors? Lucy Partington is Martin Amis’ cousin, one of his “missing,” and the question of how to overcome this kind of grief winds its away through his memoir Experience, taking on many forms – not just death, but divorce, separation, loss.

The first thing to note is the memoir’s form. Amis delivers an account of his life that is, roughly speaking, chronological, beginning from his infancy and ending with the death of his father, the novelist Kingsley Amis, in 1995, but he takes great liberties with his timeline (the artist’s prerogative), travelling forward and backward where relevant, and returning to certain key moments – his parents’ divorce, his expensive and much-publicized dental operations – where the narrative calls for it. Interspersed with these latent recollections are a series of letters from Martin to his parents and, later, father and step-mother; these are delivered without redactions or even grammatical edits (it’s edifying, to me at least, to learn that the young Martin Amis was no grammarian), and help to move the memoir forward. And I am sorry to say that, despite the deeply interesting life Martin Amis has led, Experience often needs help moving forward. For the son of Kingsley Amis, someone whose childhood was spent in the company of poets, writers and thinkers as eminent as Philip Larkin, Robert Graves and Robert Conquest, and who managed to befriend Christopher Hitchens, James Fenton and Saul Bellow, there is a stunning lack of anecdote or revelatory detail. Experience was widely anticipated because its author must – the public assumed – be so full of the kind of lurid details that made Frederick West’s murders so compelling, and yet its author largely declines to share. There is a sense, to be sure, in which this is admirable; Martin Amis has lived his life in the public eye, and has reason to believe himself victimized by this exposure. But there is also a sense in which this feels almost cowardly, and contrary to the very spirit of memoir.

Surely the best example of this authorial withdrawal is in his relationship with his father, which is portrayed as largely happy and uncomplicated, with the greatest disagreements being minor political squabbles (Martin is, predictably, against nuclear proliferation; Kingsley is, predictably, for it). Midway through the book I was astonished that two writers, father and son, could enjoy such a conflict-free relationship. Kingsley’s personal letters, largely written to Larkin, reveal a more turbulent side. This is not to say that Martin eschews personal details altogether; only that they are given sparingly, and communicated to us as reminiscences rather than with the kind of immediacy an artist can conjure. We do, however, get the customary sweeping pronouncements, whether humorous or philosophical: “It amazes me, now, that any of us managed to write a word of sense during the whole decade (the 1970s), considering that we were all evidently stupid enough to wear flares” or “When you’re without a woman, it is astonishing how quickly you become loathsome to yourself,” for example, or this rather polished sentence on Frederick West, the murderer of his cousin: “West was a sordid inadequate who was trained by his childhood to addict himself to the moment when impotence became prepotence.” Contrast that with the single paragraph Amis gives up to describe his relationship to his mother after her separation from his father and her discovery of a new man:

…I felt like an actor in a saddening dream. Because my mother had changed. […] It wasn’t the effect of the change that harrowed me but the fact of it. I went cold at the sight of this parody mother. And I felt my heart make a tactical withdrawal from her. Because you’d better not commit too much love to someone who has suddenly become changeable. Mothers, fathers, aren’t supposed to change, any more than they are supposed to leave, or die. They must not do that.

This is penetrating, poignant, even beautiful, but it’s as close as we are allowed to get.

These are perhaps petty complaints compared to the pleasures Experience offers, and the book is not without intimacy. It is no small thing to be taken inside the hospital bedroom during your father’s last days, or to have the innocence and embarrassment of your childhood laid bare, in plangent, evocative prose. Amis does this, beautifully. But it is likewise no small thing to finish a memoir and still feel its subject is a stranger to you.