From her opening sentence, Mary Karr warns us of the perils of memory: “Any way I tell this story is a lie.” She is addressing her adolescent son, her only child, and despite some early humour, we are quickly given to understand that this will be a work of expiation, or at least of explanation:

From her opening sentence, Mary Karr warns us of the perils of memory: “Any way I tell this story is a lie.” She is addressing her adolescent son, her only child, and despite some early humour, we are quickly given to understand that this will be a work of expiation, or at least of explanation:

However long I’ve been granted sobriety, however many hours I logged in therapists’ offices and the confessional, I’ve still managed to hurt you, and not just with the divorce when you were five, with its attendant shouting matches and slammed doors.

Shortly after this mea culpa, Karr references her own mother’s “psychotic episode,” which we get in greater detail as the memoir progresses: how when Mary was still a child, her mother doused her and her sister’s toys in gasoline, how she stood over them with a carving knife, thinking she would spare them by killing them. Her childhood in rural Texas is largely glossed over; instead, the narrative begins in earnest when she is 17, off to California with friends to drink, smoke and do drugs, and nursing the kind of literary love that has her reciting verses to the ceaseless waves of the Pacific. Like many before her, Karr operates under “the myth that if I could just shuffle the right words into the right order, I could get my story straight,” and so she lives the poet’s life, drinking, reading and working odd jobs to finance her reading and drinking.

Karr eventually leaves Texas for Vermont and a Master’s degree, and there she meets her future husband, Warren. It would be difficult to imagine a greater contrast. Mary is emotional, her life turbulent; Warren is stoical and meticulously organized, his daily routine – of reading, writing, running and sit-ups – precise like a metronome. Mary’s family hails from rural Texas; Warren is descended from a long line of prep school and Ivy league graduates. Here is how she reflects on those years:

Whatever the case, those years only filter back through the self I had at the time, when I was most certainly – even by my yardstick then – a certain species of crazy. But inside that was a girl starving for stability and in love with a shy, brilliant man fleeing the aristocracy he was born to.

Their love for each other has one common foundation, the love of literature, and in their own dysfunctional way they carve out a life together, with Warren stubbornly refusing any aid from his wealthy family. Change comes when Mary wants a child and Warren, though hesitant, concedes. The experience of motherhood, the challenges of labour and the nightmarish attempt to scrape together a life while working to support an infant all place immense strain on their marriage, and Karr reverts to her oldest coping mechanism, the one employed by her parents before her: alcohol.

That’s the secret to getting up: the glass talks and my neck cranes toward the drink like flower to sunbeam. My heavy skull rises, throbbing with a pulse beat. I grab the drink and let a long gulp burn a corridor through the sludge that runs up the middle of me – that trace of fire my sole brightness. A drink once brought ease, a bronze warming spreading through all my muddy regions. Now it only brings a brief respite from the bone ache of craving it, no more delicious numbness.

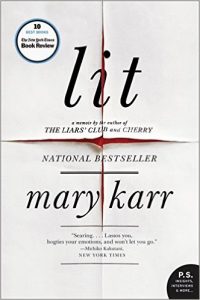

The memoir’s title, Lit, gives some hint to the dominant theme of the book, as “lit” is both shorthand for “literature” and a colloquialism – one of many – for being intoxicated. Karr’s descent into addiction is frightening and frighteningly well evoked, reminiscent of some searing passages in David Foster Wallace’s Infinite Jest, and that comparison now seems less than accidental, as Karr and Wallace met in an AA meeting, and would, when Karr’s marriage finally collapses, briefly date.

The latter half of the memoir is devoted to Karr’s rehabilitation, her escape from the prison of addiction, and this, it turns out, requires the famous “higher power” that she had spent so much of her youth gleefully mocking. She begins to pray, regularly attends church and even makes confession, and the passages describing her reconciliation with god are among the book’s most powerful.

Mock that experience as random chance if you like, but from then on, I start to arrive in the instant as never before, standing up in it as if pushed from behind like a wave, for it feels as if I was made – from all the possible shapes a human might take – not to prove myself worthy but to refine the worth I’m formed from, acknowledge it, own it, spend it on others.

Of all of addiction’s frightening consequences, surely the worst is that it forces our gaze forever inward, makes a world of our consciousness and blinds us to anything and anyone outside that misery. (Karr quotes from Milton, expressing exactly this: “Which way I fly is Hell; myself am Hell; / And, in the lowest deep, a lower deep / Still threatening to devour me opens wide, / To which the Hell I suffer seems a Heaven.” Lit is very much a journey out of hell, and Karr is compelling whether damned or saved.