It is my growing conviction that Michel Houellebecq is the most important living novelist, though it isn’t exactly easy to explain why. On a sentence-by-sentence basis, there are at least a dozen writers alive today who are his betters, and the same set of stock characters – lonely men, aging women, virile youth – appear, more or less interchangeably, in all his writings. He’s provocative, frequently crude, and pessimistic to his core; there are no transcendent relationships in Houellebecq – no happy marriages, no genuine friendships, nothing to mitigate the horrors of human suffering and the inevitability of death. When he isn’t overwhelming you with the bleakness of his worldview, he can provoke you to laughter, but it’s a bitter humour he invokes, not an edifying one, and usually serves to secure your submission to his vision. The case for his greatness, it seems to me, rests upon what he has noticed about the modern world, and the unflinching manner in which he calls us to account.

It is my growing conviction that Michel Houellebecq is the most important living novelist, though it isn’t exactly easy to explain why. On a sentence-by-sentence basis, there are at least a dozen writers alive today who are his betters, and the same set of stock characters – lonely men, aging women, virile youth – appear, more or less interchangeably, in all his writings. He’s provocative, frequently crude, and pessimistic to his core; there are no transcendent relationships in Houellebecq – no happy marriages, no genuine friendships, nothing to mitigate the horrors of human suffering and the inevitability of death. When he isn’t overwhelming you with the bleakness of his worldview, he can provoke you to laughter, but it’s a bitter humour he invokes, not an edifying one, and usually serves to secure your submission to his vision. The case for his greatness, it seems to me, rests upon what he has noticed about the modern world, and the unflinching manner in which he calls us to account.

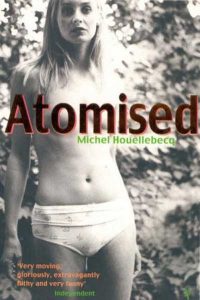

The title of his 1998 book, Atomised (The Elementary Particles in the United States), offers a clue to his central contention, one that runs through all his works like a thesis: society itself is breaking down, collapsing under the burden of too much liberalism, resulting in an an exponential increase in loneliness. Sex is celebrated, though not because it is the source of new life or the physical union of two people in love; it is celebrated for the pleasures it brings, and in a world without god or higher purpose, pleasure itself becomes a purpose, the only recognized respite from the too-real suffering of existence. In such a value system, children are at best an inconvenience, and an expensive and time-consuming one at that. Here is Houellebecq’s opening paragraph:

This book is principally the story of a man who lived out the greater part of his life in Western Europe, in the latter half of the twentieth century. Though alone for much of his life, he was nonetheless closely in touch with other men. He lived through an age that was miserable and troubled. The country into which he was born was sliding slowly, ineluctably, into the ranks of the less developed countries; often haunted by misery, the men of his generation lived out their lonely, bitter lives. Feelings such as love, tenderness and human fellowship had, for the most part, disappeared; the relationships between his contemporaries were at best indifferent and more often cruel.

I warned you, did I not, about his pessimism? The country he refers to above is France, and it’s quite a claim to make that it is “slowly, ineluctably” regressing as a nation, but opinion polls side with Houellebecq: at last asking, a staggering 88% of French men and women agreed that their country was headed “in the wrong direction.” The protagonists of Atomised are victims of France’s sexual libertinism: Bruno and Michel, two half-brothers born to the same hippie mother, Janine, whose total indifference to their lives leaves them emotionally stranded from an early age. Bruno is the first-born:

It was an uneventful pregnancy, and Bruno was born in March 1956. The couple quickly realised that the burden of caring for a small child was incompatible with their personal freedom and, in 1958, they agreed to send Bruno to Algeria to live with his maternal grandmother. By then, Janine was pregnant again, this time by Marc Djererzinski.

Her first lover, Bruno’s father, is a plastic surgeon – a career whose explosive growth was intimately tied to the changes in society inaugurated by the sexual revolution. When men and women collectively postpone marriage and child-rearing, the dating game is likewise prolonged – often by decades – and the only limit to the fun comes from time itself: skin wrinkles, breasts sag, desire deadens. Janine’s next lover, Michel’s father, is a documentary filmmaker, whose work frequently takes him abroad. He returns to their shared home one day to find the remnants of an orgy: a naked 15-year-old girl, a naked older man, muffled screams coming from upstairs, and Janine nowhere to be found:

Pushing open the door of one of the upstairs bedrooms, he smelled a retch-inducing stench. The sun flared violently through the huge bay window onto the black and white tiles where his son crawled around awkwardly, slipping occasionally in pools of urine or excrement. He blinked against the light and whimpered continuously. Sensing a human presence, the boy tried to escape; Marc picked him up and the child trembled in his arms.

Confronted with the option of raising his son alone or passing on the responsibility, Marc likewise chooses individual freedom, and drops his son off with his own grandmother. It is a fate Houellebecq well understands: his own hippie parents abandoned him to his grandmother when he was just six years old.

We need no prophet or fortuneteller to guess that the lives of children born into such negligence will be blighted, but Bruno and Michel fall apart in different ways. Bruno chooses – if he can be said to choose – the life of the libertine, pursuing casual sex and fleeting pleasure at every opportunity. Houellebecq descends into the crude whenever he describes the sexual desires of men, but even at his most shocking, he never loses sight of his central argument: that sex can only ever represent the perfection of existence for someone whose existence has been crippled. “Take him, for example – he was 42 years old. Did he want women his own age? Absolutely not. On the other hand, for young pussy wrapped in a mini-skirt he was prepared to go to the ends of the earth. Well, to Bangkok at least. Which was, after all, a 13-hour flight.” Such lines – funny as they are – rankle high-brow readers, and seem designed to provoke the likes of Michiko Kakutani, of the New York Times, who cannot see past Houellebecq’s mischievous perversity. Well, what of the following, describing the young Bruno:

At night, he dreamed of gaping vaginas. It was about then that he began reading Kafka. The first time, he felt a cold shudder, a treacherous feeling, as though his body were turning to ice; some hours after reading The Trial, he still felt numb and unsteady. He knew at once that this slow-motion world, riddled with shame, where people passed each other in an unearthly void in which no human contact seemed possible, precisely mirrored his mental world. The universe was cold and sluggish. There was, however, one source of warmth – between a woman’s thighs; but there seemed no way for him to reach it.

Here is the link between sexual desire and loneliness made explicit: the one becomes an escape from the other. And so all of life is reduced to a quest to get between women’s thighs. Michel, Bruno’s half-brother, models a different path through life: he devotes himself to science and the pursuit of knowledge, never marrying, never pursuing an intimate relationship. Houellebecq, in his subtle way, has as much fun with Michel as he does with Bruno: “In 1993 he felt the need for a companion, something to welcome him home in the evening. He settled on a white canary.” The joke, of course, is that a canary can never be a “companion,” in any real sense of the word. Michel, despite his obvious brilliance, can likewise discover no transcendent meaning to his life; scientific discoveries, professional accomplishments, the esteem of colleagues – these cannot warm a bed at night, or offer a consoling hand in times of trouble. The saddest lines in the book, to my mind, come late in Michel’s life, when he realizes that, no matter where he settles down, every apartment is destined to feel like a hotel room – a bleak fate indeed.

I consider it yet one more testament to Houellebecq’s genius that real life has come to resemble, more and more, the bleak vision he has laid out in his fiction. On the internet, in what is colloquially called “the manosphere,” two of the ideological groups vying for the interests of young men, the MGTOW (Men Going Their Own Way) and the PUAs (pick-up artists), seem like extensions of Michel and Bruno’s world views. Both camps are in broad agreement that the social contract has been broken beyond repair, and that the traditional route of monogamy, marriage and child-rearing is a fool’s errand; one side has decided to turn their backs on society, the other to enjoy its downfall as much as possible. Houellebecq, it seems, gets the last laugh.