I must begin by thanking my brother Kenneth, both for recommending Submission to me and for shipping it across the Atlantic when our dismal Montreal bookstores could not furnish a copy.

I must begin by thanking my brother Kenneth, both for recommending Submission to me and for shipping it across the Atlantic when our dismal Montreal bookstores could not furnish a copy.

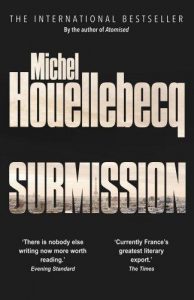

Michel Houellebecq was unknown to me before January of last year, when armed fanatics stormed the offices of French satirical cartoon Charlie Hebdo to execute men and women they viewed as blasphemers against their prophet. Houellebecq was connected to this infamous day in three respects: first, days prior to the shooting, Charlie Hebdo released a cartoon mocking Houellebecq’s predictions about France’s Islamic future; secondly, his good friend, the economist Bernard Maris, was among those killed that day; and finally, in a further twist of the knife of fate, his novel Submission was released the day of the shooting. Houellebecq promptly cancelled the book tour, prudently sheltering himself from the ensuing storm, and Submission sold more than 100,000 copies in its first week of sales. It is the fictional companion to journalist Éric Zemmour’s The French Suicide (Le Suicide Français), in that both books predict a Muslim takeover of France and both, in a testament to the national mood, were runaway bestsellers.

This prognosticating has put Houellebecq at the center of controversy, and opened him up to charges of bigotry. “France is not Michel Houellebecq,” said PM Manuel Valls; “It is not intolerance, hatred and fear.” Politicians have never needed help from writers to make fools of themselves, but their efforts at literary criticism tend to be especially risible. Submission is, indeed, a hateful novel, but its scorn is not targeted at one specific ethnic or religious minority; Houellebecq has all of French society in his sights (and, by extension, all of the Western world), and his criticisms are painful because they are so poignant.

Houellebecq’s narrator, François, is an academic who had “never felt the slightest vocation for teaching,” a middle-aged bachelor whose best days, in his own judgment, are behind him. His chief preoccupation, outside of his teaching duties, is sex, either with prostitutes or his students. He describes a pattern in his life whereby the start of the academic year will bring him a new conquest, always a young woman, who will gradually tire of him and their quasi-relationship, ending things in time for the summer, when he is condemned to rely on prostitutes once more. François perceives, accurately, that he has skipped some once-essential step, and having fallen out of this rhythm, he is perhaps condemned never to live a normal life:

The way things were supposed to work (and I have no reason to think much has changed), young people, after a brief period of sexual vagabondage in their very early teens, were expected to settle down in exclusive, strictly monogamous relationships involving activities (outings, weekends, holidays) that were not only sexual, but social. At the same time, there was nothing final about these relationships. Instead, they were thought of as apprenticeships – in a sense, as internships (a practice that was generally seen in the professional world as a step towards one’s first job). Relationships of variable duration (a year being, according to my own observations, an acceptable amount of time) and of variable number (an average of ten to twenty might be considered a reasonable estimate) were supposed to succeed one another until they ended, like an apotheosis, with the last relationship, this one conjugal and final, which would lead, via the begetting of children, to the formation of a family.

The “complete idiocy of this model,” however, is revealed to him not in his failure to adhere to it, but in the failures of the women in his life, his ex-lovers, to whom time is much crueller. (He will confess, later on, that he benefits “from that basic inequality between men, whose erotic potential diminishes very slowly as they age, and women, for whom the collapse comes with shocking brutality from year to year, or even from month to month.”) Consider Aurélie, one of François’ ex-lovers, who works as a sales representative for a wine company and, like François, is childless and unmarried. She speaks with bitterness about the men in her life before inviting François to her room, a sure sign, to him, that she had “hit rock bottom.” His description of what follows is cruel:

From the moment the doors shut, I knew nothing was going to happen. I didn’t even want to see her naked, I’d rather have avoided it, and yet it came to pass, and only confirmed what I’d already imagined. Her emotions may have been through the wringer, but her body had been damaged beyond repair. Her buttocks and breasts were no more than sacks of emaciated flesh, shrunken, flabby and pendulous. She could no longer – she could never again – be considered an object of desire.

A bleak vision, indeed: the woman condemned to sex without love, the man to sex without desire, and both miserable and unsatisfied (Houellebecq will later write, “For man, love is nothing more than gratitude for the gift of pleasure”). And Houellebecq offers us little hope of redemption, for his narrator – who is “waiting to die,” who can say, with a straight face, that he is “not for anything,” and who can sincerely suggest that a good blow job from a prostitute might “justify a man’s existence” – our everyman, is utterly unwilling and incapable of creating or embodying a change. The change, Houllebecq suggests, must be external, and it is less of a prediction than an inevitability, for the present system is so decadent, so listless and so preoccupied with present pleasures that it does not even bother to reproduce itself. That change is Islam.

Houellebecq’s vision of the Islamic takeover of France itself embodies a prophetic criticism. The National Front, led by Marine Le Pen, surges in popularity in the wake of the drastic demographic changes going on in France (the novel takes place in 2020), and in a bid to keep the Right out of power, the Left joins forces with the “Muslim Brotherhood Party,” who are supported by wealthy financiers in the Middle East. The academic community is immediately annexed by the parties of Allah, who mandate sweeping changes: segregated education for men and women, for example, as well as the firing of all female professors and the requirement that every teacher convert to Islam. Most of France’s Jews, including François’ only real love interest, Myriam, have long since fled for Israel, and much like the Nazi takeover of France, the changes are swift, sweeping and largely unopposed. They also present a choice for François: he can retire, with his pension intact, and live comfortably until the end of his days, or he can convert to Islam and continue in his job, albeit with added benefits: a drastically increased salary, for one, and the ability to take multiple, much younger wives. Given everything we’ve learned about him so far, the choice is no choice at all.