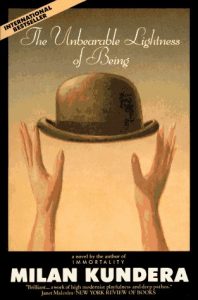

In “Lightness and Weight,” the opening chapter of Milan Kundera’s The Unbearable Lightness Of Being, the author ponders the burdens and benefits of two types of lives – the care-free, let’s say, and the weighty – with the paradox of the title in mind: how can lightness, the absence of weight, be unbearable? This philosophical introduction – Nietzsche is invoked in the very first line – coupled with the prominent narrational voice, alert us to the fact that this is not going to be a conventional novel, where fleshed out characters and detailed descriptions conspire to fool the reader into a “suspension of disbelief.” Kundera dispenses with that expectation from the start: “It would be senseless for the author to try to convince the reader that his characters once actually lived.” On the contrary, his characters, he tells us, “are born of a situation, a sentence, a metaphor, containing in a nutshell a basic human possibility… the characters in my novels are my own unrealized possibilities.” And the possibilities that obsess Kundera, and therefore guide the lives of his characters, pertain primarily to this question of being, of how to live in the world: with the freedom of lightness, of few attachments and obligations, or with the responsibilities that come with shouldering a burden.

In “Lightness and Weight,” the opening chapter of Milan Kundera’s The Unbearable Lightness Of Being, the author ponders the burdens and benefits of two types of lives – the care-free, let’s say, and the weighty – with the paradox of the title in mind: how can lightness, the absence of weight, be unbearable? This philosophical introduction – Nietzsche is invoked in the very first line – coupled with the prominent narrational voice, alert us to the fact that this is not going to be a conventional novel, where fleshed out characters and detailed descriptions conspire to fool the reader into a “suspension of disbelief.” Kundera dispenses with that expectation from the start: “It would be senseless for the author to try to convince the reader that his characters once actually lived.” On the contrary, his characters, he tells us, “are born of a situation, a sentence, a metaphor, containing in a nutshell a basic human possibility… the characters in my novels are my own unrealized possibilities.” And the possibilities that obsess Kundera, and therefore guide the lives of his characters, pertain primarily to this question of being, of how to live in the world: with the freedom of lightness, of few attachments and obligations, or with the responsibilities that come with shouldering a burden.

Milan Kundera was born in Czechoslovakia, and personally witnessed both the Nazi occupation of his country in the late 1930s, and the Soviet Union’s 1968 invasion. His brush with fascism made him a communist in his youth, but witnessing the Soviet occupation – the petty indignities it inflicted, and the hypocrisy it necessitated from occupied and occupier alike – dashed the last of his faith in any ideology, and his writing – from his first novel, The Joke, onward – has been a repudiation of collectivism and an assertion of the inherent dignity and worth of the individual. The Unbearable Lightness Of Being is set in Prague, in the years before and after the Prague Spring (the brief relaxation of central control of the economy and social life, that eventually prompted a Soviet invasion), and follows the lives of four principal characters: Tomáš, a successful surgeon and unrepentant lothario; Tereza, a beautiful young waitress who becomes Tomáš’ wife; Sabina, a painter and one of Tomáš’ many mistresses; and Franz, a young professor who falls in love with Sabina. A Venn diagram would be needed to accurately chart these romantic entanglements, but the principal actors share a burden in common: they each wrestle with questions of meaning. Tomáš sleeps with many women, but his romantic attachments to them are thin – at one point, he even forgets a lover’s face – and without the responsibility of a relationship based on mutual sacrifice, an entire realm of human feeling is denied to him. This realization comes to him while he is out at a night club with Tereza, and witnesses her dancing with a young man: “He realized that Tereza’s body was perfectly thinkable coupled with any male body, and the thought put him in a foul mood. Not until late that night, at home, did he admit to her that he was jealous.” Jealousy is an unpleasant emotion, but it’s also an undeniable sign of human attachment: you do not feel jealousy over women you do not care about, and Tomáš experiences this as a revelation. Something similar can be said of Sabina, his paramour, who prefers the unreality of an illicit affair to the potential complications of an actual relationship.

It is Sabina who provides the novel with another of its great themes in her hatred of all things “kitsch.” She is an artist, after all, and kitsch represents the inauthentic, the lazy, the wishful. But Kundera connects the concept to utopianism, and the ideological spell under which his country had fallen.

“Kitsch” is a German word born in the middle of the sentimental nineteenth century, and from German it entered all Western languages. Repeated use, however, has obliterated its original metaphysical meaning: kitsch is the absolute denial of shit, in both the literal and the figurative senses of the word; kitsch excludes everything from its purview which is essentially unacceptable in human existence.

What is utopian thinking, if not a denial of the ugliness in human existence, the conviction that it could be otherwise? She escapes, temporarily, to Paris, where she encounters widespread protests against the occupation of her country, but she declines to participate.

When she told her French friends about it, they were amazed. “You mean you don’t want to fight the occupation of your country?” She would have liked to tell them that behind Communism, Fascism, behind all occupations and invasions lurks a more basic, pervasive evil and that the image of that evil was a parade of people marching by with raised fists and shouting identical syllables in unison. But she knew she would never be able to make them understand.

One encounter with that “more basic, pervasive evil,” the one lurking in the hearts of even the most well-intentioned, has made her deeply suspicious of the motives of others, and alert to the value of ugliness – or of recognizing, not denying, ugliness. But this recognition of how not to live does not answer the question of how to live, and she, too struggles to find meaningful attachment in the world: Her drama was a drama not of heaviness but of lightness. What fell to her lot was not the burden but the unbearable lightness of being.” Her affair with Tomáš, because it is an affair, and therefore secretive and haphazard, rather than an everyday commitment, falls into the category of lightness.

Another of the book’s motifs is provided by Beethoven’s String Quartet No. 16, whose very theme is “a difficult decision,” and which employs the refrain “Es muss sein!” (It must be!) repeatedly. For Beethoven, Kundera tells us, “necessity, weight, and value are three concepts inextricably bound: only necessity is heavy, and only what is heavy has value.” Each of Kundera’s characters comes to a similar recognition: that a life without burden, without responsibility, is meaningless, and therefore unbearable. One of the burdens they elect to shoulder is romantic: the burden of a committed relationship, of making yourself vulnerable to another human being; another is political: the burden of expressing yourself honestly, of speaking out against a government eager to shut you up. They are both, in the profoundest sense, acts of love.