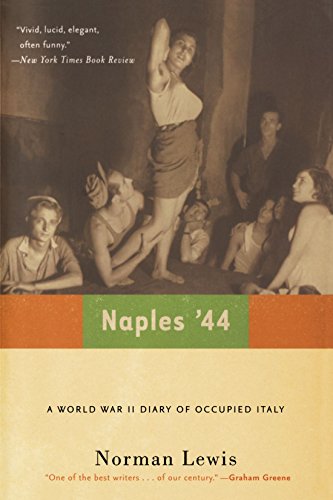

I owe to Curzio Malaparte my introduction to the sufferings inflicted on the people of Naples in 1944, the year the Allies liberated it from Nazi occupation. His book The Skin is a semi-fictionalized account of that proud city’s descent into poverty, starvation and, ultimately, humiliation, as its desperate citizens turned to crime, prostitution and supplication before the victorious and well-fed troops now occupying their country. Naples ’44, a memoir of that ugly period published in 1978, offers a single soldier’s account of Italy in this terrible intermediary period between German and American occupations. It isn’t as stylized or embellished as Malaparte’s account, but it is equally well-written, and both men capture something of the essential torment – material, of course, but also spiritual – suffered by the people of Naples, as well as the shocking indifference displayed by many of their supposed liberators.

A young Norman Lewis, serving in the British Intelligence Corps, arrived in Italy in late 1943, temporarily embedded with the American Fifth Army, and from his first description of the Italian coast, we find ourselves captivated by the beauty of his language:

A great sweep of bay, thinly pencilled with sand, was hacked with distant mountains gathering shadows in their innumerable folds. We saw the twinkle of white houses in orchards and groves, and distant villages clustered tightly on hilltops. Here and there, motionless columns of smoke denoted the presence of war, but the general impression was one of a splendid and tranquil evening in the late summer on one of the fabled shores of antiquity.

It is a safe bet that few among the liberation forces would have been able to express with such eloquence or historical understanding the captivating beauty of the coast. At this point in the war, German forces still occupy parts of Italy, and are retreating only under the cover of heavy fire, making every forward movement by the Allies perilous, and death an omnipresent reality.

In the afternoon another cautious excursion a mile or two up to the Battipaglia road. Shortly after crossing the Sele bridge, I saw a number of the German tanks which had almost reached us on the night of the 14th, and had been put out of action by the naval shelling. Several of these lay near, or in tremendous craters. In one case the trapped crew had been broiled in such a way that a puddle of fat had spread from under the tank, and this was quilted with brilliant flies of all descriptions and colours.

These scenes of death and destruction are commonplace, particularly in the early stages of the memoir-diary, before the Allies gain full control of the country, but what truly disturbs the reader are the less gruesome encounters with more mundane sufferings: the gaunt faces of the native Italians, grown too large for their clothes; the orphaned children roaming the city at all hours of the day and night; the ordinary women offering ever-lower prices to the foreign soldiers, the only people reliably supplied with food, for an hour of their company. By the estimations of the Allies’ own “Bureau of Psychological Warfare,” there are “forty two thousand women in Naples engaged either on a regular or occasional basis in prostitution. This out of a nubile female population of perhaps a hundred and fifty thousand.” In one particularly memorable scene, a handsome pair, brother and sister, approach Lewis with an offer: the sister will volunteer for service in the army brothel in exchange for regular food supplies. He has to inform them, to their surprise, that there is no army brothel.

The book’s most celebrated and often-quoted scene is also far and away its most depressing. Lewis enters a restaurant, one of the few left running, which almost by definition exists only to serve the very wealthiest Italians and the occupying forces. The waiters do double duty, dispensing the food to the customers and forcefully dragging out hungry orphans who wander inside in search of dropped morsels.

Suddenly five or six little girls between the ages of nine and twelve appeared in the doorway. They wore hideous straight black uniforms buttoned under their chins, and black boots and stockings, and their hair had been shorn short, prison-style. They were all weeping, and as they clung to each other and groped their way towards us, bumping into chairs and tables, I realised they were all blind. Tragedy and despair had been thrust upon us, and would not be shut out. I expected the indifferent diners to push back their plates, to get up and hold out their arms, but nobody moved. Forkfuls of food were thrust into open mouths, the rattle of conversation continued, nobody saw the tears.

It isn’t primarily their suffering that affects Lewis; it is the indifference of the diners to the tableau of misery before them.

The experience changed my outlook. Until now I had clung to the comforting belief that human beings eventually come to terms with pain and sorrow. Now I understood I was wrong, and like Paul I suffered a conversation – but to pessimism. These little girls, any one of whom could be my daughter, came into the restaurant weeping, and they were weeping when they were led away. I knew that, condemned to everlasting darkness, hunger and loss, they would weep on incessantly. They would never recover from their pain, and I would never recover from the memory of it.

That, in miniature, is the impact Naples ’44 has on us as readers, and what unites it so neatly with Malaparte’s The Skin: both books will convert even the cheeriest of optimists to pessimism.