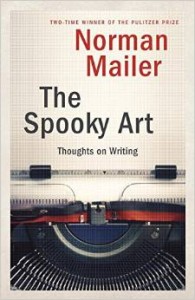

The Spooky Art is the first book by Norman Mailer I have read, which, when you consider his quondam literary fame, seems rather odd, except that his reputation – at least among readers of my generation – has fallen significantly. He was the subject of a scathing indictment by outspoken feminist Kate Millet – he returns fire in one of the essays in this book – and has since been looked upon as a kind masculine dinosaur who had the audacity to escape extinction. Emily Gould cemented that opinion when she famously referred to Mailer, Roth and Updike as “midcentury misogynists,” and though I have read enough of Roth and Updike to find that summary grossly unfair, it somehow always stuck in my mind with regards to Mailer. No doubt that prejudice wasn’t improved by Cynthia Ozick’s wonderful takedown of Mailer, which hinges on a grotesquely embarrassing sentence he coined: “Mr. Mailer, when you dip your balls in ink, what color ink is it?” In fairness to Norman, he handled his comeuppance with aplomb, but a man can only court controversy for so long before it becomes enmeshed with his public image, and the sense you get from reading The Spooky Art is that he enjoyed being the center of attention.

The Spooky Art is the first book by Norman Mailer I have read, which, when you consider his quondam literary fame, seems rather odd, except that his reputation – at least among readers of my generation – has fallen significantly. He was the subject of a scathing indictment by outspoken feminist Kate Millet – he returns fire in one of the essays in this book – and has since been looked upon as a kind masculine dinosaur who had the audacity to escape extinction. Emily Gould cemented that opinion when she famously referred to Mailer, Roth and Updike as “midcentury misogynists,” and though I have read enough of Roth and Updike to find that summary grossly unfair, it somehow always stuck in my mind with regards to Mailer. No doubt that prejudice wasn’t improved by Cynthia Ozick’s wonderful takedown of Mailer, which hinges on a grotesquely embarrassing sentence he coined: “Mr. Mailer, when you dip your balls in ink, what color ink is it?” In fairness to Norman, he handled his comeuppance with aplomb, but a man can only court controversy for so long before it becomes enmeshed with his public image, and the sense you get from reading The Spooky Art is that he enjoyed being the center of attention.

The book is an assemblage of old writings and some snippets of new wisdom organized around the subject of writing, but you don’t need to read very far before you realize that “writing,” for Norman Mailer, entails much more than craft. First and foremost there is the inner peace needed to face the monotony of writing, a task that only a profoundly disturbed person would set for himself to begin with. “One of the cruelest remarks in the langue is: Those who can, do; those who can’t, teach. The parallel must be: Those who meet experience, learn to live; those who don’t, write.” Writing, then, is already an admission of defeat, a renunciation of life. If you think this objectionable, consider how many hours of solitude the writer needs, not only to compose but also to read – who but a disturbed person would consciously choose such a life? The paradox is that a disturbed person, eager though he or she may be to commit their thoughts to writing, cannot easily sit quietly for hours on end, especially without the mental lubricants of alcohol and drugs, or at least coffee and cigarettes. This is why writing is “spooky,” because it denudes us to ourselves, forces us to face ourselves head on: “Consciously or unconsciously, writers must fashion a new peace with the past every day they attempt to write. They must rise above despising themselves.” The only dependable thing for a writer, then, is professionalism, which Mailer defines as the ability “to do a good day’s work on a bad day.” Show up at the writing desk, morning after morning, week after week, month after month – it’s as easy and as hard as that.

There’s a quasi-mysticism that creeps into his appreciation for his craft, one that at times seems gratifying, benign, even enriching (“The act of writing is a mystery, and the more you labor at it, the more you become aware after a lifetime of such activity that it is not answers which are being offered so much as a greater appreciation of the literary mysteries”), but that at other times caused me to stub my toe (“phenomena of a certain kind can be regarded provisionally as magical in those particular situations where magic offers the only rational explanation for events that are otherwise inexplicable”). These quotations appear in an essay entitled “The Occult,” in which he uses the word “magic” somewhat more literally than you might hope – after all, nothing in human history once thought of as magic has withstood our investigations – but he does manage to salvage his position by positing a disjunction between the life-giving mysteries of literature and the cold realities of “the technological society.” “When the novel is dead,” he warns us, “then the technological society will be totally upon us.” The novel, for Mailer, has a spiritual role to play, much as it does for Lionel Trilling. It is an engine of complexity, resisting the reductive and the simple, insisting at all times on complexity, shades of grey, nuance. Journalists and television shows also tell stories, but only the novel can give you the insider’s perspective on another human being, take you into their thoughts and concerns; it is the closest we can get to “walking a mile in someone else’s shoes,” and there is indeed something magical about its ability to bridge consciousnesses.

Finally, it’s worth saying a word about Mailer’s prose. He says, at one point, that the best writing combines precision with “the ring of speech,” and you may take it for a rule that when a given writer describes the “best” style or approach to writing, they are invariably describing their own style, their own approach. This may be an aspect of the “reasonably dependable ego” he deems it crucial for writers to have, but I don’t mean this as a criticism; he writes beautifully, with clarity and precision, yes, but also humour, insight and self-deprecation. The result is a style at once relaxed and personable, with frequent allusions to boxing and sex – not reading reviews of your novels would be like “not looking at a naked woman if she happens to be standing in front of her open window” – that no doubt don’t endear him to his more sensitive critics, but that do convey a strong sense of his character. (At one point, he describes his delight in arriving at a party to find present a man, a literary critic, who had savaged his most recent novel; Mailer enjoys sitting uncomfortably close to him on the couch, pressing into him while avoiding the subject of the review.)

As a guide to the craft, The Spooky Art is jumbled but insightful, less practical than spiritual, and massively inspiring. Above all, it makes me want to read more Mailer, to see for myself the relationship between theory and application.