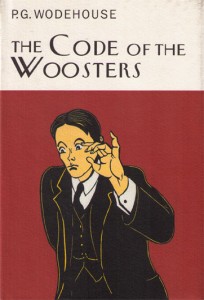

It is to Richard Dawkins, Stephen Fry and Christopher Hitchens – my beloved British triumvirate – that I owe my newfound love of P.G. Wodehouse. The Code of the Woosters, published in late 1938 mere months before the beginning of World War II, is set in the pre-war period, in a Britain much more recognizably stratified into upper and lower classes. Bertie Wooster is the novel’s central protagonist and narrator, a well-intentioned, well-heeled aristocrat whose life consists of idling, attending social events and doing his utmost to avoid marriage, something that was apparently much more difficult in the early 20th century. He is aided by his valet Jeeves, a self-described “gentleman’s personal gentleman” or “personal gentleman’s gentleman,” who is given to quoting canonical English literature and whose acumen is forever engaged in helping Bertie out of awkward social situations.

It is to Richard Dawkins, Stephen Fry and Christopher Hitchens – my beloved British triumvirate – that I owe my newfound love of P.G. Wodehouse. The Code of the Woosters, published in late 1938 mere months before the beginning of World War II, is set in the pre-war period, in a Britain much more recognizably stratified into upper and lower classes. Bertie Wooster is the novel’s central protagonist and narrator, a well-intentioned, well-heeled aristocrat whose life consists of idling, attending social events and doing his utmost to avoid marriage, something that was apparently much more difficult in the early 20th century. He is aided by his valet Jeeves, a self-described “gentleman’s personal gentleman” or “personal gentleman’s gentleman,” who is given to quoting canonical English literature and whose acumen is forever engaged in helping Bertie out of awkward social situations.

The Code of the Woosters finds Bertie in disfavor with a magistrate and his accomplice Roderick Spode, a young leader of a fascist organization – the Brown Shorts – who inspires this wonderful description: “Big chap with a small moustache and the sort of eye that could open an oyster at sixty paces.” There is a levity to Wodehouse’s writing that inspires much of the humor in his works and that makes him endlessly quotable: “It is no use telling me there are bad aunts and good aunts. At the core, they are all alike. Sooner or later, out pops the cloven hoof” or “I could see that, if not actually disgruntled, he was far from being gruntled.”

There is little in the way of underlying political messages or commentary – even when a fascist character is prominent in a novel written just prior to World War II, when Europe is on the very brink of war – but that doesn’t stop Wodehouse from delivering timeless and light-hearted observations about the human condition, particularly as concerns family and relations between men and women. And while I, in particular, enjoy the challenge of picking up on all of his literary allusions and quotations, the motivation behind reading him is very simple: he is hysterically funny. Stephen Fry compared him to Oscar Wilde, and – incredibly – it is not an undeserved comparison. Wodehouse shares Wilde’s gift for mining mundane social situations for witty insights; it is the source of his popularity and ongoing relevance, and reason enough to read him in the televisual age we live in.