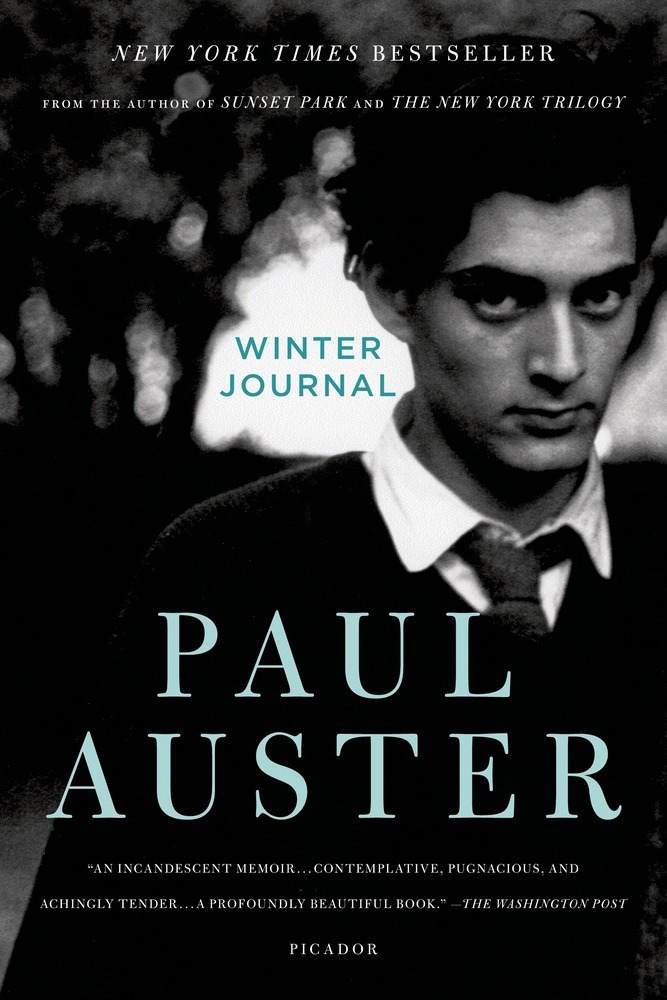

Given pages enough, and time, how would you organize the story of your life? Would you begin sensibly, that is to say, chronologically, from infancy into adulthood? Or would you perhaps single out the most impactful moments, the most important people, and tell your story through their lens? In Winter Journal, the novelist Paul Auster, now 63 years old, sobered by “the incontestable fact” that he is no longer young, reflects on his life up until this point. “Speak now before it is too late,” he cajoles himself. “Time is running out, after all.” What follows, he tells us, will be a “catalogue of sensory data,” a “phenomenology of breathing,” and true to his word, we get a panoply of sensations, from the high-minded sadness that accompanies a broken relationship or the invigorating power of new love, to the physical pain of the body. Unusually, Auster opts to write in the second person, addressing himself as if he were two people – “Your bare feet on the cold floor as you climb out of bed …” – or as if he and his reader were one person.

Auster’s breakout work was a memoir, The Invention of Solitude, published in 1982, when he was just 35, and so it’s fitting that, nearly three decades later, after a raft of prize-winning novels, he returns to the memoir form, now with more life behind him than ahead of him. Despite that sad fact, and the work’s title, this is not a sombre book, nor is it regretful; its dominant tone, in fact, is one of awe: awe at the life he has lived, the opportunities he has enjoyed, the places he has seen and the women he has loved:

You are sixty-three years old. It occurs to you that there has rarely been a moment during the long journey from boyhood to now when you have not been in love. Thirty years of marriage, yes, but in the thirty years before that, how many infatuations and crushes, how many ardors and pursuits, how many deliriums and mad surges of desire?

If you were telling your own life story, why not single out the “ardors and pursuits,” especially if, as a man, so much of your life can be reduced to just that? We certainly get a history of his infatuations, but also a series of vignettes, sometimes comic, sometimes tragic, separated by decades of life but united by a common theme. After a brief description of his sexual awakening (“Five years old, naked in the bath, alone…”), we are treated to an embarrassing episode in which he pees his pants while on a long route trip with his parents; the very next episode, 50 years into the future, describes another car trip, this time with his wife and daughter, that results in a near-fatal collision.

[…] the van is suddenly and unexpectedly upon you, and since you are looking forward and not to your right, you do not see the van as it comes crashing into your car – a ninety-degree-angle hit, straight into the front door on the passenger’s side, the side on which your wife is sitting. The impact is thunderous, convulsive, cataclysmic – an explosion loud enough to end the world.

He and his daughter walk away from the accident, but a first responder will have to cut his wife free with the jaws of life to ascertain whether or not her neck is broken – “you study the demolished car and cannot comprehend why all of you are still breathing.”

For a memoir, though, this book is at times oddly impersonal. We learn intimate details about his life, including the fact that he lost his virginity to a black prostitute or that his grandmother murdered his grandfather, but we never learn the names of his wives – this despite the fact that his first wife is the writer Lydia Davis, every bit as famous as he is – or his children. The second person narration seems oddly limiting in this respect, throwing Auster into sharp relief at the expense of almost every other major figure in his life. The startling exception to that is his mother, who is treated to an extended profile, beginning with her failed marriage to Auster’s father – a “marriage of no hope.”

You were the beneficiary of her unhappiness, and you were well loved, especially well loved, without question deeply loved. That first of all, that above and beyond everything else there might be to say: she was an ardent and dedicated mother to you during your infancy and early childhood, and whatever is good in you now, whatever strengths you might possess, come form that time before you can remember who you were.

He goes on to describe the maturation of their relationship, from his dependance on her to her eventual dependance on him, in terms both moving and relatable. But Auster’s wife of thirty years, his daughter, and his father – no doubt all major figures in his life, one would assume – are given far scanter treatment. These omissions are made all the more glaring by some of the more trivial episodes he does recount: a spat with a French landlord or an anti-Semitic piano tuner, for example.

Individually, the memories Auster conjures are often moving, no less than the meditations they provoke. But there is a distinctive lack of cohesion between the parts, and what dramatic or narrative weight he creates for us gets diluted by the diffuse episodes. Ultimately, it is its journalistic qualities that rob Winter Journal of much of its power, weakening it as a memoir.