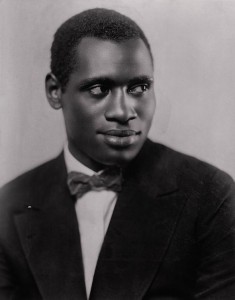

Paul Robeson may very well be the most talented man you have never heard of. He was a professional football player, internationally recognized star of stage and screen, civil rights advocate of high moral principle and remarkably little regard for the the pains these principles would inflict upon his career, and among the greatest Shakespearean actors of the 20th century.

Paul Robeson may very well be the most talented man you have never heard of. He was a professional football player, internationally recognized star of stage and screen, civil rights advocate of high moral principle and remarkably little regard for the the pains these principles would inflict upon his career, and among the greatest Shakespearean actors of the 20th century.

He was born in 1898, in Princeton, New Jersey, the son of escaped slaves. His mother, impaired by poor sight, died in a house fire when he was only six years old. His father was a minister who would often allow Paul to give sermons in his place (no doubt the source of Paul’s booming voice and affinity for language) but disputes with the white financiers of his congregation led him to resign, forcing him to do menial odd jobs to support his children, who moved with him into a small attic above a store. In high school, the young Paul acted, performed in chorus groups and thoroughly dominated his athletic competition in basketball, football, baseball and track.

He won a scholarship to Rutgers University, only the third African American ever to enroll there, and the only one to attend at the time. Here he continued to play sports, particularly football, the game best suited to his prodigious athletic gifts and unique combination of size and speed, but not without relentless racist taunting – not only from opposing teams, who often refused to play against a team with a black player, but from his own fans and teammates as well. But these indignities served only to further highlight his eventual triumph: Robeson graduated Phi Betta Kappa, with varsity letters in multiple sports, as well as recognition for his outstanding contributions to the debate teams and school choruses (the school glee club, incidentally, never fully embraced him: membership required attendance at social events that were strictly “whites only”).

Robeson went on to attend Columbia Law School, studying the law – a law that was openly prejudiced against him – between practices for the numerous plays and musicals he performed in, as well football matches for the now-defunct Akron Pros. After graduating, he made a brief entrance into a legal career but quickly realized that, once again, the pervasive racism within the field would forever stymy his progress. It was at this point that he landed the lead role in Eugene O’Neill’s All God’s Chillun Got Wings, a brand new play whose plot featured a black man having sex with a white woman. This was treated as a national scandal; debates were organized as to whether or not this constituted lascivious or immoral subject matter, worthy of the same kind of prohibition that visited James Joyce’s Ulysses. The KKK issued death threats, not only to the writer but to the cast members as well, should they dare to perform.

And Robeson, as he had done throughout his life, persevered: reviews were glowing, not only of the play but of its star as well. A young Hart Crane, unknown to the world in 1923 and only a year younger than Robeson himself, was fortunate to attend that first performance and found himself shaken by Robeson and horrified at the childish national reaction.

Broadway and cinematic roles followed, and Robeson became a beloved international star. His performance as Othello remains definitive (I ask you to listen to his voice, so deep and regal it might command the heavens to part, and you will grasp some small measure of his acting prowess). But he was presented with an offer that his principles could not countenance: keep silent, remain apolitical, a mere entertainer, and enjoy a life of ease and luxury. This he could not do. He spoke out against Vietnam, against the pervasive racism and hypocrisy of American society; he defended the Republican cause during the Spanish Civil War, criticized the colonial policies of Western nations and openly defended communism. In 1951, he presented a document before the United Nations charging the United States of being complicit in a genocide for their failure to prevent lynchings.

For these and other unpopular opinions, he found himself blacklisted under McCarthyism, and as quickly as fame and opportunity had come they were stolen from him. He lived the remainder of his life in comparative poverty and ill health, struggling with depression, anxiety and, quite possibly, bipolar disorder. No doubt he would have played a prominent role in the Civil Rights Movement had not his health quickly begun to fail him.

You would be hard pressed to find in one human being a greater assemblage of talents, but it is his principles and the conviction with which he pursued them that make him worthy of our admiration.