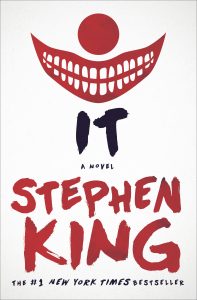

It has been over 30 years since the first publication of Stephen King’s It, his eighteenth novel, and time has not eroded its influence or dulled its ability to scare. Even as I type, Hollywood is busily at work bringing another incarnation of King’s nightmare to the silver screen. But, for my part, the King phenomenon has largely passed me by. With the exception of his On Writing, a nuts-and-bolts instructional manual for aspiring writers, and an excellent one at that, I had never before picked up a King work. It was my initiation, a good-faith attempt to give King his due and overcome my prejudices about genre writing, and I am proud to report something like that conversion has indeed happened. Setting aside my preconceptions, and delving into this 1,200-page brick of a book, I discovered a more accomplished and ambitious writer than I had expected.

It has been over 30 years since the first publication of Stephen King’s It, his eighteenth novel, and time has not eroded its influence or dulled its ability to scare. Even as I type, Hollywood is busily at work bringing another incarnation of King’s nightmare to the silver screen. But, for my part, the King phenomenon has largely passed me by. With the exception of his On Writing, a nuts-and-bolts instructional manual for aspiring writers, and an excellent one at that, I had never before picked up a King work. It was my initiation, a good-faith attempt to give King his due and overcome my prejudices about genre writing, and I am proud to report something like that conversion has indeed happened. Setting aside my preconceptions, and delving into this 1,200-page brick of a book, I discovered a more accomplished and ambitious writer than I had expected.

The plot is familiar to many, but worth recounting in brief nonetheless. There are two main timelines in the book: the first kicks off in 1957, in the small town of Derry, Maine, where a young boy is murdered while trying to recover a paper boat from a storm drain. His arm is ripped off at the socket, and the last thing he sees before he dies is the image of a malevolent clown, sneering at him from the gutter. The boy is George Denbrough, younger brother of one of the book’s main characters, Bill Denbrough, and the clown is Pennywise, a shapeshifting spirit that has haunted Derry for centuries, manifesting once every 27 or so years to terrify the town’s children by taking the form of their greatest fears – a vampire, say, or a werewolf, or a mummy. A group of children who have encountered Pennywise, in one form or another, and lived to tell about it, band together, forming the Loser’s Club, so named because each of the children has been ostracized or isolated for one reason or another. Bill, for example, suffers from a terrible stutter; Stan Uris is Jewish, in a predominantly Christian town; Mike Hanlon is black in a predominantly white town; Ben Hanscom is obese; Beverly Marsh, the group’s only girl, comes from a poor family, and her father is physically abusive; Richie Tozier has a quirky sense of humour, slipping into different characters, accents and voices at random; and Eddie Kaspbrak, whose mother almost certainly has some form of Munchausen syndrome by proxy: she has convinced him that he has asthma, and has even enlisted the help of his doctor – who provides Eddie with a fake inhaler – to solidify the illusion.

The second timeline, in 1984, kicks off with a phone call from Mike Hanlon, who has never left Derry, to the far-flung members of the Loser’s Club, who have found varying degrees of success in the wider world. Mike is calling with bad news: the killings have started again, Pennywise has returned, and it is time for the fellowship to reunite and put an end to the nightmare once and for all. King intercuts the earlier, 1957 timeline with the later 1984 one, in such a way that we rarely advance further in one without shortly being caught up in the other. The final result yields two climaxes, two final showdowns with the murderous spirit, and this intricate structure is one of the book’s unqualified successes, and a testament to King’s prowess as a storyteller.

But what about those of us suspicious of genre writing? One of King’s characters in the novel becomes a writer in his adult life, and he recounts his experience at a university writing workshop, where he was frustrated by his instructor’s insistence that every story be loaded with sociopolitical commentary: “Why does a story have to be socio-anything? Politics … culture … history … aren’t those natural ingredients in any story, if it’s told well?” King is anticipating his critics, and indeed he has a point, for It is so expansive that it does encompass politics, culture and history. Homophobia provides one of the book’s biggest themes; the second spat of killings, for example, begins when two bullies throw a gay man off a bridge, and there is an extended discussion on Derry’s only gay bar, and the town’s reaction to its existence. History likewise plays a major role in the book: the town of Derry is old, older than the founding of the country, and its history is told as deftly as the lives of the book’s characters, and with as much importance. But King’s largest triumph in It pertains to his characters and their families. To truly instill fear in his readers, he knows he has to make them emotionally invested in his characters, and this is no easy task; on the contrary, it is the hardest part of good writing, and It is at its best in the moments between the horror, when tensions are built by describing, for example, the growing rift between Bill Denbrough’s parents after the murder of their son, or the anxiety Beverly Marsh feels in her own home, knowing even the mildest provocation might trigger her father’s fists.

In such moments, at the intersection of storytelling and craft, King’s prose rarely lags behind his ambitions, and though there are a handful of headscratchingly odd narrative choices – odd even by the standards set by a story about a shapeshifting clown – they never fully diminish our enjoyment or break King’s spell.