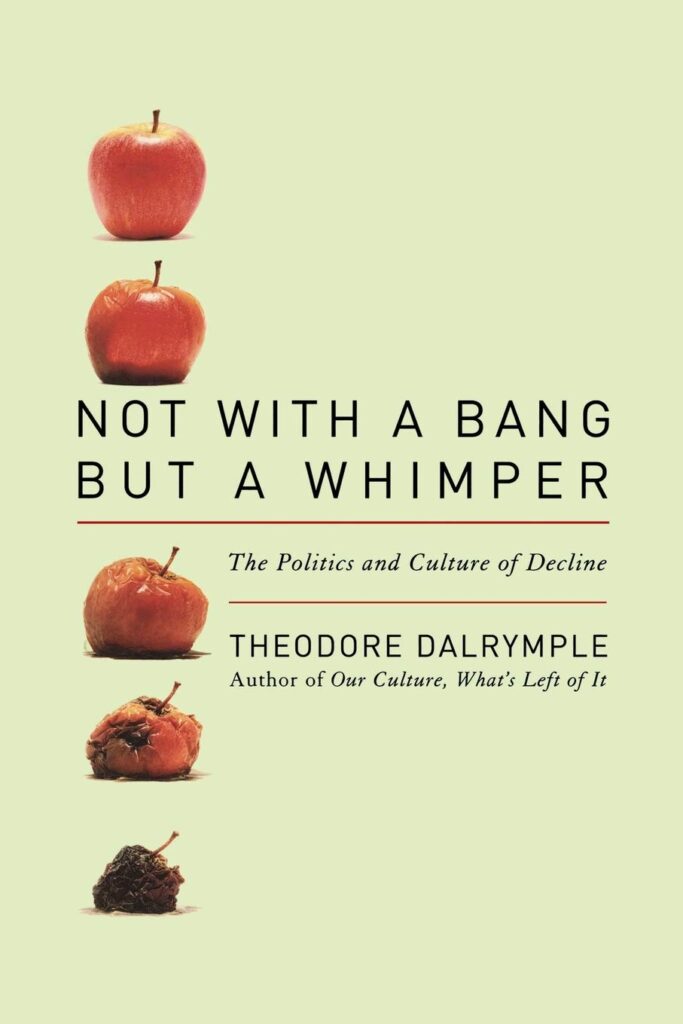

Something I’ve been wondering, of late: did the Romans of the fourth century AD know that their empire was in decline? Certainly there were philosophers and politicians expressing their dismay, but did the average man and woman know that their years of ruling much of the known world would soon be at an end? There are, at present, many prophets of decline; in fact, they seem to multiply daily. Few of them can approach Theodore Dalrymple (real name Anthony Daniels) for clarity of vision and breadth of knowledge. Daniels is a British doctor, with experience treating the sick in Britain’s slums and in some of the poorest countries in Africa, and the animating force behind much of his writing came from the recognition that Africa’s poor now possessed a dignity and sense of purpose painfully lacking from the materially better off British underclass. Not With A Bang But A Whimper: The Politics and Culture of Decline appeared in 2008, a year of global financial crisis, yet the decline it prophecies is not economic but spiritual and cultural. Don’t look to the GDP or the trade deficit: look to the decline in educational standards, or the proliferation of graffiti on once-pristine public squares; consider the degradation of language in everyday use, or our increasingly slovenly standards of dress. Our new aristocracy, wealthy and well-educated, make a point of not noticing these deteriorations, or even celebrating them as gains in authenticity or democracy – though never, of course, for their own children – and many of the essays collected here make painfully clear the link between our moral decline and the suffering of a growing underclass left without direction and purpose.

The early essays cover notable writers as varied as Samuel Johnson, Arthur Koestler and Henrik Ibsen, in an erudite and passionate way precious few English professors could equal. Johnson, Dalrymple tells us, is admirable because he was “profoundly anti-Romantic,” possessed of an integrity that would not bow before the demands of genius or status. By way of example, Dalrymple cites a letter Johnson wrote in response to a request that he write a recommendation to the Archbishop of Canterbury on behalf of the petitioner’s son, that he might be admitted to a prestigious university (a thoroughly modern dilemma). Johnson’s reply did not mince words: “You ask me to solicit a great man, to whom I never spoke, for a young person whom I had never seen, upon a supposition [the merit of the young applicant] which I had no means of knowing to be true.” His moral standards even extended to the high in stature, for he ends his biography Life of Mr. Richard Savage with a warning that anticipates Raskolnikov:

This relation [the biography] will not be wholly without its use if … those who, in confidence of superior capacities or attainments, disregard the common maxims of life, shall be reminded that nothing will supply the want of prudence, and that negligence and irregularity long continued will make knowledge useless, wit ridiculous, and genius contemptible.

The desire to exempt oneself from the moral standards others hold in common is surely ineradicable – otherwise what need of a public morality? – but Johnson and Dalrymple wisely hold the line. Perhaps the most salient characteristic of our new upper class, by contrast, is a contempt for any overarching public morality whatsoever: do as you will might be the mantra of the moderns. In “What the New Atheists Don’t See,” he offers an explanation for this transformation. The theory uniting the “Four Horsemen” of the New Atheist movement is that religion is an obstacle to reason, and reason offers our best for a better future, free from bigotry and prejudice and conflict. What none of them can see, in Dalrymple’s view, is why religion arose in the first place. Eradicate God and you bring that problem – or problems – back into view. What is it all for? A good man might answer with charity, and a curious man with science or exploration. An artist will point to the work yet to be done. These are all rational answers, but they are not the only rational answers. “After all, the greatest enjoyment of the usages of this world, even to excess, might seem rational when the usages of this world are all that there is.” No higher purpose and no afterlife? Why not then merely chase after the pleasures, however fleeting, and run from the pains, however rewarding in future?

Dalrymple cites two modern writers as prophets of this brave new world where god is dead and reason is ascendent: J.G. Ballard and Anthony Burgess. In “The Marriage of Reason and Nightmare,” Dalrymple points to Ballard’s novel Crash as a perfect product of a world without transcendent meaning: “The book is a kind of visionary reductio ad absurdum of what Ballard sees as the lack of meaning in modern material abundance, in which erotic and violent sensationalism replace transcendent purpose: the book’s characters speed to the sites of auto accidents to seek sexual congress with the dying bodies and torn metal.” In “A Prophetic and Violent Masterpiece,” he charts the morality of Burgess’ A Clockwork Orange, which envisions a world in which the young run rampant and the elderly, unable to control them, lock their doors and refrain from leaving their homes at night. “Intimidation of the aged and contempt for age itself are an essential part of the youth culture: no wonder aging rock stars are eternal adolescents, wrinkled and arthritic but trapped in the poses of youth. Age for them means nothing but indignity.” A youth culture of rebellion and contempt for authority might be another consequence of God’s demise, for if this life is there is, every passing year only brings us closer to the end of the party – why wouldn’t we worship youth and hold on, with all our might, to the affectations of our salad days?

The later essays in this collection leave behind the realm of the imagination to focus on Britain in the 21st century, where abstract ideas intersect with an all-too concrete reality, and no one alive has done a better job cataloguing our myriad absurdities or plumbing the depths of our dystopia. We get essays on, for example, police whistleblowers angered by the sclerotic and idealistic forces of bureaucracy that have only made it harder to do traditional police work – the kind that prioritized order and public safety – by saddling officers with more training courses on prejudice, diversity and discrimination than on actual police work; teachers fed up with curriculums that make learning a secondary consideration, and students so ill-cared for at home that schools become daycares. It is to Dalrymple’s credit not only that he can clearly perceive and denounce these changes, but that he can treat of them with a measure of humour. The decline may now be irreversible, but we will go down laughing.