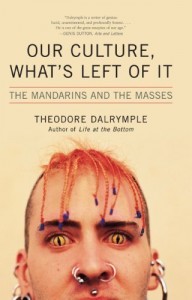

I have lately had the pleasure of discovering Theodore Dalrymple (real name Anthony Daniels), a retired doctor turned essayist whose small but devoted following – among whom number both Thomas Sowell and Charles Murray – prize him for his unflinching portrayals of poverty, despondency, crime and neglect. Having spent his working life attending to the sick and wounded in various African countries, and as a prison doctor in England, he has had a tremendous amount of contact with a subset of humanity that inspires both pity and fear: drug dealers, rapists, murderers, batterers and addicts. His experiences inform his worldview, which, though often extremely bleak, never descends to pessimism. Indeed, his every essay is an affirmation of the value of personal responsibility, which he views as the sine qua non for human happiness, ambition and self-respect, and a foundational virtue for any civil society. Our Culture, What’s Left Of It collects essays written between the end of the 20th century and the book’s publication in 2005, most of which are available on the City Journal website. The essays center on common themes – the abandonment of aesthetic and artistic standards, the loosening of moral strictures, the shibboleths of the modern Left – but demonstrate an immense cultural knowledge, from Shakespeare to Goethe, Turgenev and T.S. Eliot, that shames most modern sociology writing.

I have lately had the pleasure of discovering Theodore Dalrymple (real name Anthony Daniels), a retired doctor turned essayist whose small but devoted following – among whom number both Thomas Sowell and Charles Murray – prize him for his unflinching portrayals of poverty, despondency, crime and neglect. Having spent his working life attending to the sick and wounded in various African countries, and as a prison doctor in England, he has had a tremendous amount of contact with a subset of humanity that inspires both pity and fear: drug dealers, rapists, murderers, batterers and addicts. His experiences inform his worldview, which, though often extremely bleak, never descends to pessimism. Indeed, his every essay is an affirmation of the value of personal responsibility, which he views as the sine qua non for human happiness, ambition and self-respect, and a foundational virtue for any civil society. Our Culture, What’s Left Of It collects essays written between the end of the 20th century and the book’s publication in 2005, most of which are available on the City Journal website. The essays center on common themes – the abandonment of aesthetic and artistic standards, the loosening of moral strictures, the shibboleths of the modern Left – but demonstrate an immense cultural knowledge, from Shakespeare to Goethe, Turgenev and T.S. Eliot, that shames most modern sociology writing.

As I write, some two thousand National Guard troops have been dispatched to Ferguson, Missouri, to quell the rioting and looting that have taken place in response to an unwelcome courtroom verdict. I have been thinking a great deal lately about societies, specifically about the ties that bind. It seems to me that civil society is maintained by a perilous balancing of competing interests – too many to adumbrate here – and that many of the institutions that were long thought to be the foundations of this peace have been steadily eroding for a very long time. Among these I count the family, basic unit of society, as well as religion, law, commerce and what you might call culture: manners, language, morality and art. We in the West are rapidly approaching a state of existence entirely without precedent in our history, one in which increasingly fewer children are born to married couples, the marriage rate is in steady decline and Arnold’s Sea of Faith has all but dried up. To these new developments, most members of my generation have demonstrated a profound indifference; many are even welcoming, seeing little in the past worth salvaging. But, staunch atheist that I am, I cannot cheer these new developments unreservedly. Can the mass of men find purpose in a secular world, or will the void left by Christianity fill itself with ever more radical forms of belief? Can the human family survive in a world without religion? And, if the family falls, how long before the laws – and, by extension, society – collapse as well?

There is one other symptom of our cultural decline, one far less alarming than falling birthrates and broken families, but one that we would perhaps have the most cause to regret. This is the loss of our artistic tradition. As Ortega y Gasset warned, the standards set by our artistic heritage have proven too onerous for the average citizen, and, rather than aspire to greatness, we have preferred the leveling power of relativism, by which the subjective experiences of the critic takes precedence over the imperatives of art. In such a society, simple pleasures – or, to use Dalrymple’s more effective term, “vulgar pleasures” – reign. Anything that is easy to grasp and quick to gratify finds a mass appeal, and even the tastemakers of society, Dalrymple’s mandarins, fall over themselves to gush praise, the better to demonstrate their democratic bonafides.

Dalrymple charts this decline. He traces its sources and follows its path through our culture with depressing insightfulness. Most importantly, he forces us to confront its consequences. You cannot unflinchingly promote “transgressive” as a term of universal approbation in art without one day confronting the “artist” who smears human feces on a canvas anymore than you can advocate for the relaxing of social and sexual mores without bearing witness to the growing number of single mothers or the legions of children who will grow up without knowing what it is to live in a stable home or to have loving, caring parents. That he manages to do all of this in electric prose and with evident and profound compassion only adds to his esteem in my eyes.