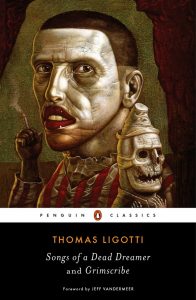

The Penguin Classics publishing house pulled American horror writer Thomas Ligotti from the relative obscurity of genre fiction two years ago, when they re-issued two of his short story collections, Songs of a Dead Dreamer (1986) and Grimscribe (1991), making him one of just ten living authors to have “classic” status officially bestowed upon him. Prior to this reissue, Ligotti’s works were difficult to get a hold of – part of their cult appeal, no doubt – but he has since become the talk of the literary world, his writings very much in vogue, and his very popularity has in turn inspired all kinds of gloomy speculation about our present moment, since if a writer as bleak and unredeeming as Ligotti is popular, well, things really and truly must be grim.

The Penguin Classics publishing house pulled American horror writer Thomas Ligotti from the relative obscurity of genre fiction two years ago, when they re-issued two of his short story collections, Songs of a Dead Dreamer (1986) and Grimscribe (1991), making him one of just ten living authors to have “classic” status officially bestowed upon him. Prior to this reissue, Ligotti’s works were difficult to get a hold of – part of their cult appeal, no doubt – but he has since become the talk of the literary world, his writings very much in vogue, and his very popularity has in turn inspired all kinds of gloomy speculation about our present moment, since if a writer as bleak and unredeeming as Ligotti is popular, well, things really and truly must be grim.

Ligotti and I share a common love for the philosopher Emil Cioran, a Romanian-French nihilist and, in my judgment, one of the 20th century’s greatest stylists, and one of his bleakest pronouncements might be taken as the starting point for every single one of Ligotti’s short stories: “There are questions which, once approached, either isolate you or kill you outright.” Ligotti and Cioran know that, while it isn’t possible to think yourself into life, a clever, wide-eyed person might easily think himself out of life, and happiness – to no small degree – therefore depends on circumscribing our range of reference, leaving unquestioned the pillars of our existence. This Cioran does not permit, and nor does Ligotti, and it now seems to me deeply fitting that Cioran’s fictional counterpart must be a horror writer, since that’s exactly the feeling nihilism threatens us with. Here, for example, is one of Ligotti’s characters, one of his outsiders who has died to life:

As a young student in philosophy I used to say to myself, ‘I am going to learn the madness of things.’ This was something I felt I needed to know – that I needed to confront. If I could face the madness of things, I thought, then I would have nothing more to fear. I could live in the universe without feeling I was coming apart, without feeling I would explode with the madness of things that to my mind formed the very foundation of existence. I wanted to tear off the veil and see things as they are, not to blind myself to them.

The gamble, of course, is that what you perceive behind that veil might not be benign, might not sustain life but destroy it. The standard horror tropes are employed: serial killers, vampires, cultists, and malevolent spirits, but the point is never the horror or suspense – though Ligotti is adept at building both – but the psychic payout that comes from contact with “the madness of things,” the underlying reality we normally avoid at all costs. “If things are not what they seem – and we are forever reminded that this is the case – then it must also be observed that enough of us ignore this truth to keep the world from collapsing.” How safe and secure is the suburban existence so many Americans aspire to? Ligotti will introduce a serial killer into a child’s bedroom, dashing that dream forever. Another story details the arrival, from Europe, of a group of vampires, visiting family in the States – whom they promptly devour. Vampires or no vampires, are we not often bloodied by the people who claim to care most about us?

Ligotti’s fiction – like Cioran’s stylized philosophical musings – does not make for easy reading. Every story, every bleak vision and nightmare version of reality bludgeons us, unrelentingly, with some aspect of life we’d sooner look away from, one of the “grotesque ultimatums of creation” that compromise life itself. But, Ligotti would claim, that is the price you pay for clear sight and an uncompromising look at existence.