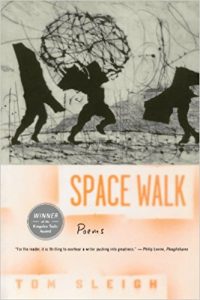

Tom Sleigh is an American poet, playwright, journalist and academic, the recipient of a Guggenheim grant, two National Endowment for the Arts grants, a John Updike Award, the Kingsley Tufts Poetry Award, and the prestigious Shelley Award from the American Society of Poets. He has taught creative writing at NYU, the University of Iowa, Dartmouth, John Hopkins University and UC-Berkeley – the most prestigious creative writing programs in the United States – and yet until very recently I had never heard of him. So it goes. Space Walk, his sixth volume of poetry, was published in 2007, and it seems both strangely of that moment in time and transcendent of it.

Tom Sleigh is an American poet, playwright, journalist and academic, the recipient of a Guggenheim grant, two National Endowment for the Arts grants, a John Updike Award, the Kingsley Tufts Poetry Award, and the prestigious Shelley Award from the American Society of Poets. He has taught creative writing at NYU, the University of Iowa, Dartmouth, John Hopkins University and UC-Berkeley – the most prestigious creative writing programs in the United States – and yet until very recently I had never heard of him. So it goes. Space Walk, his sixth volume of poetry, was published in 2007, and it seems both strangely of that moment in time and transcendent of it.

There’s a cynicism to so many of these poems, latent even in the most harmless subject matter, that seems to me to recall a societal attitude after two Bush terms and a series of inescapable wars in the Middle East. “Oracle,” the volume’s second poem, begins in the past, as the poet narrator recalls attending the launching of a rocket his father had some hand in designing:

Because the burn’s unstable, burning too hot

in the liquid-hydrogen suction line

and so causing vortices in the rocket fuelflaming hotter and hotter as the “big boy”

blasts off, crawling painfully slowly

up the blank sky, then, when he blinksexploding white hot against his wincing

retina, the fireball’s corona searing

in his brain, he drives with wife and sonsthe twisting road at dawn to help with the Saturday

test his division’s working on: the crowd

of engineers surrounding a pit dug in snow

The men working on the rocket have mundane concerns: that it fly straight and true, as it has been designed to do, and that its success will shield them from layoffs. But then there is a turn. We learn his father has been “gone ten years,” and remembrance of his father’s death – peaceful, in his own home, in the company of family – prompts Sleigh to an ugly comparison:

The scales, weighing

one man’s death and his son’s grief against

a city’s char and flare, blast-furnace heat meltingto slag whatever is there, then not there –

doesn’t seesaw to a balance, but keeps shifting,

shifting… nor does it suffice to make simplecorrespondences between bunkers and one man’s

isolation inside his death, a death

he died at home and chose… at least insofaras death allows anyone a choice, for what

can you say to someone who’s father or mother

crossing the street at random, or runningfor cover finds the air sucked out

of them in a vacuum of fire calibrated

in silence in a man’s brain like my father’s

In Iraq and Afghanistan, the American military deployed “fuel-air explosives,” originally used in Vietnam because caves and tunnels were no shelter against their secondary effect, which was to suck the air out of the blast radius, creating a vacuum that would collapse victims’ lungs, rupture eardrums and dislocate eyeballs. Anyone not killed by the initial blast had a slow, agonizing death awaiting them. Sleigh knows this because he spent nearly a decade as a journalist working in the Middle East, and so he can’t help but draw some causal link, however tenebrous, between his father’s work and the terrible uses rockets have been put to in the intervening years.

There’s a similar turn in “First Love,” a poem about – what else? – a rape. It is our poet’s first date with the woman in question, and they are lying in each other’s arms when she opens up to him:

This pillow talk she tells you, confidant, lover for the night,

as you wonder what it’s like for her, having you,

wanting you near, her trust so intimately

estranging as she tells you what he did to her

that even as you hold her you want to pull away:

and what makes her want to tell you, fear, disgust,

anger at what men might be, and some men are?

There is no moment so innocent or pure as to be safe from the revelation of evil, or the possibility of evil. Yet another poem takes place in a charming seaside cafe, filled with young people, and yet our poet finds himself in the bathroom where one man, in particular, is “stinking up the place.” The poet “revels” in the man’s stink, “as if it told me a kind of truth about myself,” and his mind wanders to Lear and a nameless grief. “Pain’s never / so articulate as when it can’t find the words / but stains the heart the variegated colors / of shit we take for granted.” Just then, the man whose bowel movements stunk up the bathroom emerges, “and he’s so handsome, so perfect in his white shirt / his jeans, the hair on his well-muscled arms / light and downy.” He exits the bathroom, leaving his filth behind, leaving our poet in contemplation. Perhaps that is the healthy thing to do, to walk away rather than dwell, make uncomfortable connections, but that is precisely what Sleigh cannot do, and what he forbids us from doing as well.