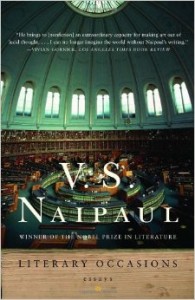

V.S. Naipaul’s Literary Occasions collects miscellaneous writings and speeches, including his Nobel prize lecture, from a career that spans the better part of a century. Born in Trinidad, in the small borough of Chaguanas, Vidiadhar Surajprasad Naipaul won an academic scholarship to Oxford, where he rather daringly elected to study English literature before pursuing writing full time in London. Literary Occasions is heavily autobiographical, an exploration of the events, places and writers that shaped his life. It is also my introduction to Naipaul, whose much-lauded A House For Mr Biswas sits, unread, on my bedside table.

V.S. Naipaul’s Literary Occasions collects miscellaneous writings and speeches, including his Nobel prize lecture, from a career that spans the better part of a century. Born in Trinidad, in the small borough of Chaguanas, Vidiadhar Surajprasad Naipaul won an academic scholarship to Oxford, where he rather daringly elected to study English literature before pursuing writing full time in London. Literary Occasions is heavily autobiographical, an exploration of the events, places and writers that shaped his life. It is also my introduction to Naipaul, whose much-lauded A House For Mr Biswas sits, unread, on my bedside table.

The first and most salient of Naipaul’s explorations is his identity as an Indian living in Trinidad, a society without a stable past and, consequently, no literary tradition. He describes his difficulties with reading, with entering into the worlds of Dickens or Waugh – two writers his journalist father was quick to introduce him to. How can you approach these quintessentially British writers if you have not only never been to England but never lived in a metropolitan city, never known a society more complex than a village? The young Naipaul instead turns to the cinema for his imaginative escapes (“I don’t think I overstate when I say that without the Hollywood of the 1930s and 1940s I would have been quite spiritually destitute”), before finding in Joseph Conrad and Rudyard Kipling a link to England’s literature that did not depend on a British upbringing.

The next step for Naipaul is convincing himself his upbringing, his people and his small, out-of-the-way town are subjects worthy of literature, that there are stories worth telling in Trinidad no less than London:

Fiction or any work of imagination, whatever its quality, hallows its subject. To attempt, with a full consciousness of established authoritative mythologies, to give a quality of myth to what was agreed to be petty and ridiculous–Frederick Street in Port of Spain, Marine Square, the districts of Laventille and Barataria–to attempt to use these names required courage.

He begins with the stories most immediate to his experience, stories of his Trinidadian neighbours and townsmen, and gradually he comes to find in them a gateway into his own experiences, the means of making sense of his own life. “Half a writer’s work,” Naipaul famously writes,” is the discovery of his subject,” and his triumph would come in the conversion of a perceived weakness – his hometown devoid of any coherent literary tradition – into a strength, a source of inspiration.

I was particularly attracted to the honesty with which Naipaul discusses writing, his earnest portrayal of his difficulties and the madness of the creative process. That even a Nobel laureate, writing towards the end of his successful career, can vividly recall the anxieties of the blank page gives me no small comfort.