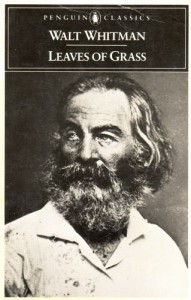

I first read Walt Whitman’s Leaves of Grass in 2005, on the 150th anniversary of its publication, and I must confess that it confused me unlike any poetic work I had yet read. Shakespeare, Tennyson, Keats, Poe – these were the poets of my youth, and poetry, to me, meant rhyme and meter and end-stopped lines. But it was not Whitman’s formal strangeness that made me uneasy. Of the two pillars of American poetry, Dickinson and Whitman, the reclusive New Englander seemed much less threatening, much less imposing. I distrusted Whitman’s presumptuousness from the very opening lines: “I celebrate myself, / And what I assume you shall assume, / For every atom belonging to me as good belongs to you.” This, to be sure, is the very essence of poetry: in writing about personal pain, desire, love or loss, the poet ends up describing our own feelings, bridging the consciousness divide in that miracle we’ve called art, but what right did even Whitman have to assume this connection? Shakespeare earns our imaginative empathy, with or without our consent – how dare Whitman take it for granted?

I first read Walt Whitman’s Leaves of Grass in 2005, on the 150th anniversary of its publication, and I must confess that it confused me unlike any poetic work I had yet read. Shakespeare, Tennyson, Keats, Poe – these were the poets of my youth, and poetry, to me, meant rhyme and meter and end-stopped lines. But it was not Whitman’s formal strangeness that made me uneasy. Of the two pillars of American poetry, Dickinson and Whitman, the reclusive New Englander seemed much less threatening, much less imposing. I distrusted Whitman’s presumptuousness from the very opening lines: “I celebrate myself, / And what I assume you shall assume, / For every atom belonging to me as good belongs to you.” This, to be sure, is the very essence of poetry: in writing about personal pain, desire, love or loss, the poet ends up describing our own feelings, bridging the consciousness divide in that miracle we’ve called art, but what right did even Whitman have to assume this connection? Shakespeare earns our imaginative empathy, with or without our consent – how dare Whitman take it for granted?

Inextricable from his project of establishing communion with his reader is the democratic spirit of the poem, so often commented upon. Like Blake before him, he does “not decline to be the poet of wickedness,” presenting himself instead in terms utterly relatable:

Walt Whitman, an American, one of the roughs, a kosmos,

Disorderly flesh and sensual… eating drinking and breeding,

No sentimentalist… no stander above men and women or

apart from them… no more modest than immodest.

Some 200 years after John Donne warned that “no man is an island entire of itself,” and told how “any man’s death diminishes me, / because I am involved in mankind,” Whitman makes a parallel claim, surely invoking Donne’s democratic spirit: “Whoever degrades another degrades me… and whatever / is done or said returns at last to me, / And whatever I do or say I also return.” But in claiming so much, in casting so wide a net, Whitman risks alienating his reader, for who can be anything can also be nothing. He escapes that trap by trusting in the ability of his Me to contain his reader: “I do not ask who you are… that is not important to me, / You can do nothing and be nothing but what I will infold you.” This is the very source of Whitman’s famous boast:

Do I contradict myself?

Very well then… I contradict myself;

I am large… I contain multitudes.

Few poets can honestly boast that they contain multitudes, but a quick glance at the rival factions that have found in Whitman a flag bearer reveal him to be prescient as always.

Much of Leaves of Grass is given to prophetic boasting and quasi-mystical assertions about the eternity of existence and I think, if I may be permitted the opinion, that the whole poem is much improved by the many revisions he later made. There is a lyrical greatness that punctuates sections of the poem’s more bloated mystical musings. Consider, for example, section 52:

The spotted hawk swoops by and accuses me… he

complains of my gab and my loitering.I too am not a bit tamed… I too am untranslatable,

I sound my barbaric yawp over the roofs of the world.The last scud of day holds back for me,

It flings my likeness after the rest and true as any on the

shadowed wilds,

It coaxes me to the vapor and the dusk.I depart as air… I shake my white locks at the runaway

sun,

I effuse my flesh in eddies and drift it in lacy jags.I bequeath myself to the dirty to grow from the grass I

love,

If you want me again look for me under your bootsoles.You will hardly know who I am or what I mean,

But I shall be good health to you nevertheless,

And filter and fibre your blood.Failing to fetch me at first keep encouraged,

Missing me one place search another,

I stop some where waiting for you.

This, to my mind, is Whitman at his best, the harmonious marriage of sentiment and song culminating in such memorable lines as “If you want me again look for me under your bootsoles.” Even the sexual aspects, so scandalous in his day, are presented with singular beauty. Who but Whitman would sound a “barbaric yawp,” or make light of it? Or boast of “effusing” his flesh in eddies?

Whitman is one of poetry’s most distinctive voices, the progenitor of Stevens, Crane and even, despite himself, T.S. Eliot, and Leaves of Grass, so strange and powerful, remains America’s central poetic work. And though this influence has also not always been comfortable or benign (see, for example, Pound’s “A Pact“), its endurance amply testifies to Whitman’s unique genius.