Few American statesmen of the 20th century are as famous or as polarizing as Henry Kissinger. The recipient of the 1973 Nobel Peace Prize has been variously described as a genius and a war criminal; the inspired architect of a delicate balance of power between Russia, China and America and an egomaniacal liar whose backdoor machinations destabilized whole regions of the globe. At the height of his fame, he could be seen attending movie premieres with Hollywood starlets before flying off to secret meetings in Paris, Beijing, Moscow, Tehran and Israel, logging vastly more travel time than any previous Secretary of State.

Few American statesmen of the 20th century are as famous or as polarizing as Henry Kissinger. The recipient of the 1973 Nobel Peace Prize has been variously described as a genius and a war criminal; the inspired architect of a delicate balance of power between Russia, China and America and an egomaniacal liar whose backdoor machinations destabilized whole regions of the globe. At the height of his fame, he could be seen attending movie premieres with Hollywood starlets before flying off to secret meetings in Paris, Beijing, Moscow, Tehran and Israel, logging vastly more travel time than any previous Secretary of State.

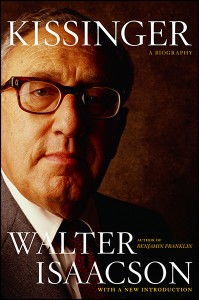

Walter Isaacson, one-time CEO of CNN and recent biographer of Steve Jobs, is just one of several writers and historians who have tackled Kissinger’s life, though beginning, as he did, late in Kissinger’s career, Isaacson had the benefit of records and documents unavailable to the earlier chroniclers. The result is not an authorized biography – Kissinger was given no right to approve or even read its contents prior to publication – but one that manages to be both critical and laudatory of a man who is rarely seen in anything but black and white. Isaacson provides an amusing example of the type of ire Kissinger had provoked among his critics:

When George Ball, the veteran American diplomat, sent the manuscript of a new book to an editor, he was told: “We’ve got one big problem here. In almost every chapter, you stop what you’re saying and beat up again on Henry Kissinger.” Ball replied: “Tell me what chapters I’ve missed and I’ll add the appropriate calumnies.”

Moreover, as Isaacson is well aware at the outset, Kissinger was intimately involved with some of the period’s most divisive events, from Vietnam to Watergate, and it is unlikely that many of his readers are approaching this book without some firmly held preconceptions. For my part, I knew very little about Kissinger personally and less about his involvement in the events that transpired during his tenure as National Security Advisor and Secretary of State.

Isaacson begins his story in Furth, in Germany, where Henry Kissinger is born to a young Jewish family in time to witness the rise of Nazism. The young Kissinger spent hours each day in required religious study, escaping only to play soccer – a perilous activity for a young Jewish boy, as they were quickly banned from using public fields – or bury himself in more secular reading. Thanks to his mother’s prescience, the Kissinger family were able to leave Germany for New York before the bigotry he experienced turned lethal, but he would never forget his hometown’s descent into barbarism. America provided Kissinger education and opportunity: a brief stint in the army, made more comfortable by his proficiency in standardized tests, led him into military intelligence and, eventually, a return to his native land, where he worked as a counter-intelligence officer, helping to rid the German countryside of its entrenched Nazi personnel and restore order to towns and villages that had experienced a complete civic breakdown.

With the aid of a military grant, Kissinger attended Harvard, earning a political science degree, summa cum laude, in 1950; in a fitting example of both the scope of his mind and the depth of his ambitions, his graduate thesis was entitled “The Meaning of History.” It stretched to several hundred pages and prompted a prohibition against overly-long theses, aptly named the “Kissinger rule,” that remains in effect to this day. His thesis provides an important insight into his worldview, as when he writes, on the very first page:

Whenever peace – conceived as the avoidance of war – has been the primary objective of a power or a group of powers, the international system has been at the mercy of the most ruthless member of the international community.

The foremost example of such a situation was also the most recent: Nazi Germany rose to power thanks to the complacency of its rivals, and their eagerness to placate Hitler — but Kissinger, in arguing for a “stability based on an equilibrium of forces,” has in mind Austrian and German statesmen like Klemens von Metternich and Otto von Bismarck, successful practitioners of so-called realpolitik and important intellectual influences on Kissinger. The détente Kissinger would later orchestrate with the Soviet Union – a clever mixing of concessions of demands that brought down tensions and opened diplomatic channels – had its origins in this thinking and these statesmen.

Aided by an astounding amount of research, Isaacson traces Kissinger’s rise to power and impact on the global world order, but the most intriguing insights have to do with Kissinger’s character. Preternaturally brilliant, Kissinger is nonetheless deeply insecure, eager for the approval of his superiors and threatened by his equals. With subordinates, he could be contemptuous, dismissive and condescending, but he would chasten his disrespect with charm and a self-deprecating wit. One staffer related an incident in which Kissinger tasked him with writing a 100-page paper on a potentially volatile situation in Vietnam. After presenting him with his completed work, Kissinger returned it, via an intermediary, with a single comment affixed to the front: “Is this the best you can do?” The staffer promptly rewrote and resubmitted the paper, only to receive the exact same comment. This repeated itself several times until, finally, the exasperated underling personally handed Kissinger his work, remarking that he could find nothing more to improve. “Excellent. I’ll finally read it then,” replied Kissinger. With the press, Kissinger was unusual: whereas most politicians restricted access and exposure to their critics, Kissinger was eager to make converts of even his most virulent critics. Isaacson relates several examples of him making personal phone calls and even home visits to writers and journalists who have just disparaged him, eager to debate a specific point or redeem his actions. But these constitute the upside to Kissinger’s insecurities and personal foibles.

His relationship with Richard Nixon – an equally volatile and insecure man, and not above playing petty mind games – would bring out the best and worst of him, and Isaacson devotes the majority of this 800-page book to their years together. Readers will be horrified to discover just how far both men were willing to go to prop up their egos or settle petty scores, or – in the worst of cases – to what extent United States diplomacy was held hostage to personality rather than process. Though Isaacson exculpates Kissinger for Watergate, he does a convincing job showing how his personality – his insecurity, his paranoia, his need for reassurance – helped create the atmosphere in which a Watergate seems almost inevitable. On Vietnam, Isaacson is much harder on Kissinger, blaming his obsession with the “credibility” of the United States in the eyes of its adversaries for the infamous Christmas bombings of 1972 and his eagerness for personal acclaim for the breakdown in diplomacy that preceded the bombings.

Isaacson’s Kissinger is no war criminal, no debased egomaniac eager for power at all costs; he is, in the end, an almost tragic figure, admirable in his aims and achievements, pitiable in his failings, and detestable in his manipulations.